Telok Ayer Street is truly Singapore’s representative street of religious harmony. Several major places of worship – a mosque, Indian Muslim shrine, Chinese temple and church – have made this street, a short 350m-long stretch between Boon Tat Street and Cecil Street, their home for more than a century.

All the four religious buildings – Al-Abrar Mosque, Nagore Dargah Indian Muslim Heritage Centre (formerly the Nagore Dargah shrine), Thian Hock Keng Temple and the Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church – have been gazetted as Singapore’s national monuments. In addition to the Telok Ayer’s conservation list are the Ying Fo Fui Kun Building and Singapore Yu Huang Gong Temple.

Telok Ayer Street

In Malay, telok means bay and ayer is water, referring to the seafront where Telok Ayer Street once ran past. It was one of the earliest streets in Singapore, and it took the form of a road as early as 1836. The Telok Ayer vicinity was designated as a Chinese district by Sir Stamford Raffles in the 1820s and its seafront and docking bay had served as one of the earliest landing sites for Chinese immigrants, especially the Hokkiens from the Fujian province of Qing China.

With their arrivals at Singapore in waves, the Chinese immigrants soon formed the largest community at Telok Ayer. Chinese religious buildings and clan associations popped up rapidly. During Chinese festivals, Telok Ayer Street would be adorned with colourful banners and flags, where thousands of spectators crowded along the street to watch the interesting performances by the Chinese processions, acrobats, and marching bands.

The street in the 19th century was shared by the Chinese, Indian and Muslim immigrants. The Indian immigrants would work as milk traders – many could be seen walking along the street with buckets of milk slung across their shoulders – or labourers at the harbours, loading and unloading cargo from the merchant ships docked at the Telok Ayer Basin.

By the late 19th century, Telok Ayer became a commercial and trading centre. But the issues of pollution and overcrowding bothered the street. In 1891, a large fire destroyed many shophouses and other properties. The merchants began to move out of Telok Ayer for other suitable trading places along the Singapore River, resulting in the declining importance of the street.

In the mid-19th century, Indian convicts were roped in for the land reclamation from the Singapore River mouth to Telok Ayer. By the early 1900s, the area known as Shenton Way today was formed. Telok Ayer Street no longer faced the waterfront; the coastline was shifted several hundreds of metres away.

Today, rows of refurbished pre-war shophouses line up along both sides of the street, witnessing the tremendous changes of Telok Ayer in the past 150 years.

Al-Abrar Mosque

The Al-Abrar Mosque, also known as Masjid Chulia, had its roots all the way back to 1827, when it began in a simple hut. In the 1850s, the mosque was upgraded to a brick building to serve as the primary place of worship for the South India’s Tamil Muslims who worked and lived around the Singapore River area.

The architectural setting of Al-Abrar Mosque blends easily into the facades of the shophouses at Telok Ayer Street. The Indo-Islamic architectural styled mosque faces the direction towards Mecca, but like other shophouses, it also has a five-foot way. A second storey, jack roof, prayer room and an upper gallery were added to the mosque building in a $1-million renovation project in the late eighties, but the mosque’s most iconic features belong to its twin octagonal minarets, each topped with a crescent and star.

The Al-Abrar Mosque was gazetted as a national monument on 19 November 1974. Today, the mosque premises can accommodate up to 800 worshippers, many of them working in the offices nearby.

Nagore Dargah Indian Muslim Heritage Centre (former Nagore Dargah Shrine)

Completed in 1830, Nagore Dargah is a memorial or cenotaph, in the shape of an Indian Muslim shrine, built by the Chulias from South India. The shrine commemorates Sayyid ‘Abdul Qadir Shahul Hamid (1490-1557 or 1579), a South Indian saint and Islamic preacher who was widely respected for his propriety and holiness.

Initially known as Shahul Hamid Dargah, the limestone building was designed and built as a replica of the original shrine in India. Like Al-Abrar Mosque, Nagore Dargah Shrine was gazetted as a national monument on 19 November 1974, and underwent major restoration works in 2007. The shrine’s most eye-catching features – its four corner minaret towers topped with small domes – were carefully restored and touched up.

Officially reopened in 2011, the shrine was converted into an Indian Muslim heritage centre that has galleries and exhibitions showcasing the pioneers of the Indian Muslim community in Singapore.

Thian Hock Keng Temple

Thian Hock Keng, whose name means “palace of heavenly happiness” in Hokkien, first existed in the early 1820s as a small temple located at the seaside of Telok Ayer Basin. It was dedicated to Mazu, the sea goddess believed by its devotees who would give blessings and protection to the seafarers.

In 1842, with the generous funding from various local Chinese businessmen such as Tan Tock Seng (1798-1850), a larger and much more elaborated Thian Hock Keng was built. Costing almost $30,000 (in Spanish silver dollars), the temple was completed with all building materials and skilled craftsmen imported from China. It was said that not a single nail was used in the construction of the temple.

Thian Hock Keng was later added a Chung Wen Pagoda, Chong Boon Gate and Chong Hock Pavilion. In 1907, the temple received its recognition from the Qing Empire when Emperor Guangxu (1871-1908) bestowed on it an imperial scroll with the words “Bo Jing Nan Ming” (波靖南溟, “The waves are calm in the South Seas” in Chinese).

Thian Hock Keng was also home to the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan (clan association), founded in 1840 to provide assistance such as accommodation, jobs and burial services to the early immigrants. On 28 June 1973, Thian Hock Keng was added to the national monument list, while major restoration works were carried out at the temple premises in the late nineties.

Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church

The Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church joined other religious places of worship at Telok Ayer Street in 1925. The church, however, was established much earlier in 1889. Founded by Benjamin Franklin West, a doctor and missionary, in a rented old shophouse at Upper Nanking Road, the church reached out to the Chinese immigrants, especially the opium addicts, with sermons and services in Hokkien. Hence, in its early days, it was known as the Hokkien Church.

The church expanded in the late 19th and early 20th century, accepting members of different dialect groups. With its increasing number of followers, the church had to look for larger premises. Therefore, it was relocated several times to Boon Tat Street, Neil Road and eventually its current location at the junction of Telok Ayer Street and Cecil Street, where it bought the land for $3,600. The Chinese Methodist Church at Telok Ayer started as a tent and zinc hut, before they were replaced by the current building, designed with a unique mixture of European and Chinese styles.

During the Second World War, a buffer wall was added to the church building as a protection against stray bullets and bombs. As many as 300 Chinese took refuge in the church, and members were encouraged to attend the Sunday services during the harsh and difficult Japanese Occupation.

On 23 March 1989, the Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church, on its 100-year anniversary, was preserved as one of Singapore’s national monuments. Today, it is the oldest Chinese-speaking Methodist church in Singapore.

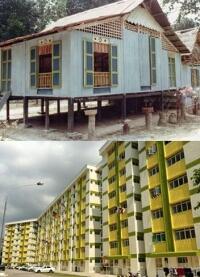

Telok Ayer Street in the Past Century

Also read Singapore’s Street of Religious Harmony (Part II) – Waterloo Street.

Published: 14 September 2016

Updated: 25 November 2017

Do you mean between Boon Tat and Amoy Street

Hi, the mosque, shrine and temple are between Boon Tat and Amoy Streets, while the church is a little further down Telok Ayer Street, near its junction with Cecil Street.

Telok Ayer St a nod to Singapore’s religious diversity

21 July 2017

The Straits Times

Telok Ayer Street was once part of Singapore’s shoreline, and migrants who arrived by sea built their places of worship nearby.

The area displays remarkable religious diversity even now, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in a Facebook post yesterday. He went on a walking tour of five places of worship along the street on Wednesday, and met leaders of the church, temples, mosque and shrine that have been there for more than a century.

Race, language and religion are faultlines that have torn many societies apart, Mr Lee noted in his post, which came on the eve of Racial Harmony Day.

“Singapore is a rare and precious example of a multi-racial, multi-lingual and multi-religious society where people live harmoniously together,” he wrote.

“This is not by chance. The government and the different communities worked hard together to make this happen.”

The Harmony in Diversity Gallery, which houses exhibits and interactive features that highlight the common thread among the different religions, is one such collaboration, said Mr Lee.

He stopped at the gallery in Maxwell Road, where he met members of the Inter-Religious Organisation (IRO), and wrote: “Long may we live peacefully and harmoniously in multi-racial and multi-religious Singapore.”

He also posted a photo of one of its exhibits, a trick-eye mural of a kopitiam, which he said was an important common space for Singaporeans of all races and religions.

Mr Lee’s first stop on Wednesday was the Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church, where services are still conducted in Hokkien. It was set up for immigrants from China’s Fujian province, and during the Japanese Occupation provided them refuge.

Mr Lee then went to the Al-Abrar Mosque, which served the Chulias – Tamil Muslims who were among Singapore’s earliest immigrants. He next visited the Thian Hock Keng Temple, one of the country’s oldest Hokkien temples, then moved next door to Taoist temple Singapore Yu Huang Gong.

The Taoist temple was previously the site of Keng Teck Whay Association, which was started in 1831 by 36 Hokkien Peranakan merchants from Melaka. It still houses the Peranakan ancestral hall and clan complex.

Mr Lee ended his tour at the Nagore Dargah Indian Muslim Heritage Centre. Originally a shrine built in honour of holy man Shahul Hamid from India, the centre now has an exhibition that pays tribute to the contributions of Indian Muslim pioneers here.

Mr Lee wrote: “My thanks to the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Inter-Religious Organisation and members of the different faith communities in Singapore for helping to build a harmonious and peaceful Singapore.”

http://www.straitstimes.com/politics/history-of-harmony-along-telok-ayer-st

Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church unearths time capsule 100 years after it was laid

16 February 2024

The Straits Times

Among the stories passed down by generations of Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church members are those of the church’s role during World War II, when it provided shelter from bombs to people living in the area and beyond – including the relatives of a current church member.

Almost a century old, the church’s building in Telok Ayer has a storied past, having witnessed several milestones in Singapore’s history.

But one story about the building containing a time capsule had circulated over decades with seemingly no substantiation or conclusion until Feb 7, when a century-old steel box was pulled from the church’s wall.

Opened at the church’s second building in Wishart Road, Telok Blangah, on Feb 14, the capsule contained a Bible, a hymnal and meeting minutes, among other items.

Mr Tan Chew Lim, 74, a lay leader of the church and a retired professor in computer science, said regular churchgoers had heard by word of mouth that the church contained a time capsule, but no concerted effort was made to recover it over the years.

That changed about two months ago, when members of the church’s archives committee – which is currently curating materials for a heritage gallery to be launched in celebration of the church building’s 100th anniversary in 2025 – discovered an article from The Malayan Saturday Post that detailed the laying of the church’s foundation stone on Jan 9, 1924, and the placement of the time capsule under it.

Mr Goh Yat Teck, who heads the church building’s centennial celebration committee, pursued the lead in the 1924 article and worked with other church leaders and consultants for the church’s ongoing restoration works to locate and extract the time capsule.

The 72-year-old said he had envisioned laying a time capsule as part of the upcoming celebration, and was pleasantly surprised to be able to retrieve one placed by the church a century ago.

“I’m very excited, now we have something to display during the church building’s 100-year exhibition,” quipped Mr Goh, adding that the church building’s centennial celebrations have “suddenly become a big event” with the discovery, arousing even the curiosity of The Methodist Church in Singapore, which oversees Methodist churches here.

Founded in 1889, Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church is the first Chinese Methodist Church in Singapore, established about four years after Methodist missionaries arrived in 1885.

Its Telok Ayer building – gazetted a national monument in March 1989 – was completed in 1925 and is currently closed for extensive restoration works, which are slated to be done in January 2025.

The building last underwent major restoration works in the early 1990s.

Among the artefacts from the capsule that might offer clues about the evolution of the Methodist faith here is a Chinese translation of the original 1784 Book of Discipline of the Methodist Episcopal Church – a “rule book” for Methodist churches, which had its first version published in the United States.

While Methodist churches in Singapore have since 1976 been governed by a Book of Discipline published and regularly reviewed by the local Methodist governing body, a comparison of the capsule’s rule book with one presently used is likely to yield insights on historical changes in the church.

The capsule also contained minutes of a 1923 meeting by the Finance Committee of the Malaysia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, which bore the names of Anglo-Chinese School and Methodist Girls’ School, reflecting the ties these institutions have to the Methodist movement in Singapore.

Overseeing an about six-hour-long extraction procedure on Feb 7 was Mr Wong Chung Wan, technical director of material specialist Maek Consulting.

Church leaders both on-site and online watched on, with about 20 of them joining in at any point of time to observe the proceedings virtually via videoconferencing platform Zoom.

Mr Wong’s team started by using a surface penetrating radar to identify the exact position of the capsule underneath the church’s marble foundation stone, which was laid on a wall facing Telok Ayer Street.

Once the position was confirmed, contractors removed the wall layer by layer, cutting through plaster and other materials to expose the time capsule.

But they encountered several challenges as they dug.

First, a portion of the time capsule was directly underneath the foundation stone when accessed from the side of the wall facing Telok Ayer Street.

As extracting the capsule from this side of the wall would increase the risk of damaging the stone, a decision was made to instead remove the capsule from the other side of the wall.

Second, there was no cavity surrounding the time capsule, which would have allowed it to be easily removed when exposed.

Instead, the capsule had been embedded into the wall, within what seemed like a concrete cradle that was created to hold it, then covered with bricks and mortar.

The tight construction made it as if the capsule was one of the bricks forming the wall, Mr Wong said.

As such, cuts had to be made according to the outline of the box in the brick-and-mortar portions of the wall that surrounded it, leading to a protracted extraction that took about twice as long as initially predicted.

At about 5.10pm on Feb 7, Reverend Gregory Goh, president of The Methodist Church in Singapore’s Chinese Annual Conference – a grouping of 17 of the 46 churches under the larger Methodist body – removed the capsule, which measured 30cm by 30cm by 5cm.

To avoid damaging the capsule and its contents, those handling it had to put on gloves.

The box was left to rest on acid-free paper in an environment with a humidity of about 50 per cent, prior to being opened.

Rev Goh said he felt a sense of reverence and awe when he held the capsule for the first time.

“I felt connected to our forefathers, and encouraged that their act of faith has stood for 100 years,” he said.

In front of about 100 church leaders and members on-site, and about 150 online, Mr Wong unpacked the box on Feb 14, prising its lid open with a screwdriver before carefully removing each item in it.

Occasionally, a cloud of dust emerged from the box as each artefact was pulled out, and when they were flipped open.

Onlookers gasped as he presented each item to them, many amazed by the good condition the paper artefacts were found in – prints were legible, despite some rust and mould damage.

Mr Tan Hua Joo, chairman of the Local Church Executive Committee, said the church intends to display the time capsule’s contents in its new 2,345 sq ft heritage gallery come January 2025, and that it will be free for all to visit.

Reverend Edmund Koh, Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church’s pastor-in-charge, said he hopes the capsule’s discovery and extraction will inspire the church’s current generation of members to, like their forefathers, “leave a beautiful legacy for those who come behind us”.

https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/telok-ayer-chinese-methodist-church-unearths-time-capsule-100-years-after-it-was-laid