According to Singapore’s geological map, the island’s strongest rock formation is found at the Gombak Norite, where its rock is tested to be more than ten times stronger than concrete. During its heydays, there were nine quarries operated at Gombak Norite. The Bukit Timah granite formation, on the other hand, covers an area of 200 square kilometres and stretches from Woodlands and Sembawang to Bukit Batok. The rock formation in this vast region is about six times stronger than concrete.

Gombak Norite also contains some rock formations that are millions of years old, although Singapore’s oldest rock is found at Pulau Tekong’s Sajahat Formation, which is estimated to be 300 million years old.

Little Guilin

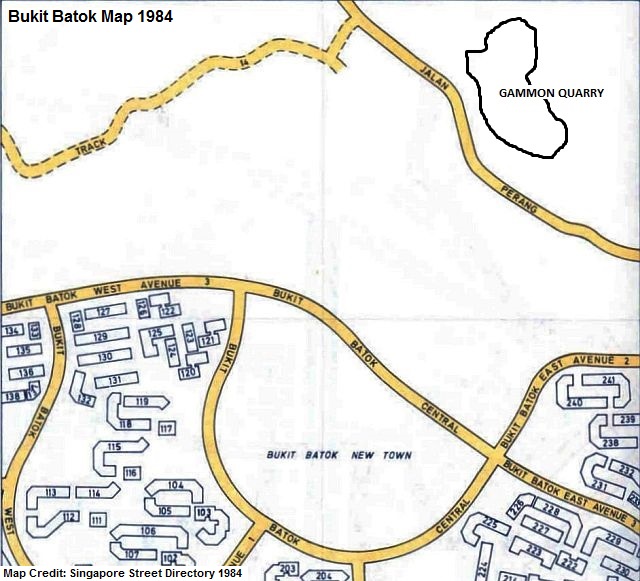

It is here at Gombak Norite where the former Gammon, Seng Chew, Lian Hup and Poh Hin Quarries once operated. By 1984, the Gammon Quarry was disused, and a year later, the authorities decided to convert it into a park. Hence, Little Guilin, with its tranquil lake and towering rock cliffs, was born, named after the famous natural granite formations in Guilin, China.

Little Guilin’s highest point reaches 133m, making it the second tallest hill in Singapore after Bukit Timah Hill, which is also a huge block of granite, standing at 163.63m above sea level.

The Little Guilin project was in-charged by the Housing and Development Board (HDB), which initially wanted the abandoned quarry to be filled and a road built over it. Before the preservation decision was made, the board surveyed the site and faced two difficult problems – preventing the place from becoming a safety hazard to the residents of the new town, and making sure it would not develop into a stagnant, mosquito-breeding ground.

By then, the water-filled quarry was one or two metres above the “safe” depth, and there were suggestions to lower the water level, but this would result in the water losing its shifting lights and sparkle. Hence, a low granite retaining wall was built at the edges of the quarry. In this way, visitors could be prevented from getting too close and falling into the waters while the water level was retained.

The second problem was more difficult in solving. As the land around the quarry slopes away from it, rainwater tends to flow away rather than into it. But HDB’s engineering team in the end managed to locate a small quarry at a higher ground to supply Little Guilin with an adequate supply of fresh water.

The development of Little Guilin was completed by the mid-eighties. Part of Jalan Perang, a long narrow road that was once the only accessible way to Gammon Quarry, was rebuilt as Bukit Batok East Avenue 5. In 1990, the Bukit Gombak Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) Station was opened, providing additional convenience to the new scenic spot.

In the vicinity also lies the the former Seng Chew Granite Quarry, sitting on a small hill about 500m north of Little Guilin. Like the former Gammon Quarry, it was also previously accessible only by Jalan Perang. After its abandonment, rainwater filled it up and the former quarry became a lake.

The development of Bukit Batok Town Park saw one side of the once-heavily forested hill trimmed to become the contoured slopes today. A drainage system is also built to allow excessive water from Seng Chew Quarry, especially during the thunderstorms, to flow down along the slopes to the underground canals.

Granite in Demand

A search with the Registry of Companies (ROC) shows that the company operating Seng Chew Quarry had existed from 1949 to 1960. The period between the fifties and seventies was indeed the golden era for local granite quarrying industry; numerous quarry companies were set up in Singapore due to the increasing demand for granite, such as Koko, Malaya, Jurong, Lian Moh, Chih Yee, Asia, New Asia, Eng Kee, Lam Eng, Atlas and Gim Huat.

In 1950, there were calls to tap the granite resources at the Bukit Timah Hill. Approving the proposal would be disastrous, as sections of the hill would be blown up and its virgin forest destroyed. Fortunately, the government carried out a series of studies, assisted by a University of Malaya geologist, and concluded that the Mandai and Pulau Ubin quarries would be able to supply sufficient granite for Singapore for another hundred years.

For the other existing Bukit Timah quarries, the Commission of Enquiry into Granite Resources and Nature Reserve recommended their closures to prevent their encroachment into the forest reserve. However, behind strong economic forces, their quarrying activities would continue until the late eighties.

But by 1995, the major Singapore Quarry, Hindhede Quarry and Gali Batu (“to dig for rocks” in Malay) Quarry had ceased in their operations and became part of the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve.

Kampong Quarry

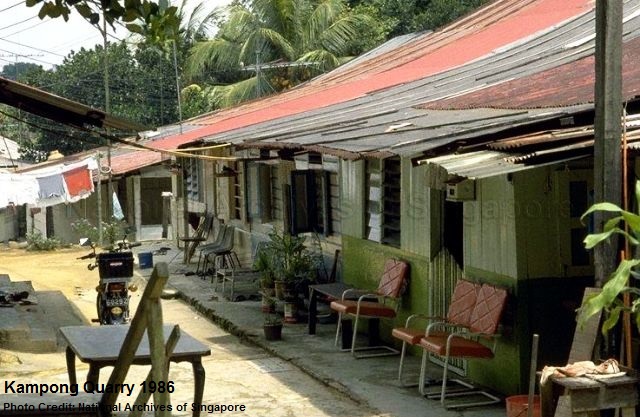

A small village called Kampong Quarry once flourished at Hindhede Road, near Bukit Timah Road 8th milestone. The Hindhede Granite Quarry had already been in existence when the village was built during the Japanese Occupation. The kampong, by the mid-fifties, had expanded to about 200 Malay residents living in 24 attap-and-zinc houses.

As the village grew in size, it became sub-divided into Kampong Quarry Bawah (“lower quarry village” in Malay), Kampong Quarry Tengah (“middle quarry village”) and Kampong Quarry Hanyut (“lost quarry village”). The name “lost” village was derived in the fifties, when the residents living there, many of them new settlers, had no occupation licenses and their houses were unnumbered. As a result, their village was not “officially” considered to be in existence.

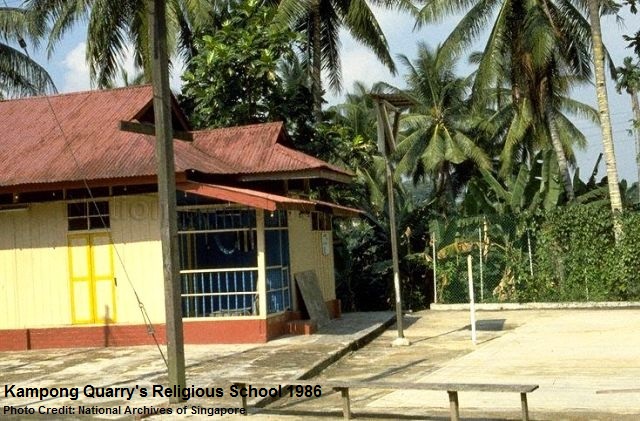

Life for the residents at Kampong Quarry was difficult, especially in the fifties and sixties. The community was basically a fringe railway settlement, and the settlers who arrived there were taking refuge from one thing or another. The small humble village had no market, cinema, clinic or primary and secondary schools. A religious school, though, was available for the children.

Things would only improve for Kampong Quarry, as common amenities were added, in the seventies and eighties .

The track to Kampong Quarry was full of potholes, which filled with water whenever it rained. Dozens of granite-laden trucks plied daily past the village to Hindhede Quarry, stirring up a flurry of dust that polluted the houses.

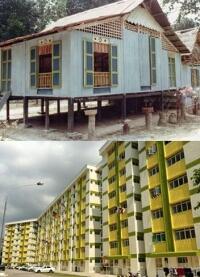

By the mid-eighties, it was clear that the village would be affected by Bukit Timah’s redevelopment. For many residents, the nights of drinking coffee and chit chatting under the coconut trees would soon be over. And so was the familiar sound of the siren warning twice a day, at 11.20am and 4pm, before the blasts in the quarry.

By the late eighties, Kampong Quarry was almost vacated, after most villagers had left and resettled at the HDB flats.

Ubin’s Quarries

Other than mainland Singapore, Pulau Ubin was another rich source of granite. Granite quarrying was once a major industry on the island, supporting Singapore’s construction sector and providing ample employment opportunities for the locals. There were once five quarries at Pulau Ubin – the Kekek Quarry, Balai Quarry, Ubin Quarry, Pekan Quarry and Ketam Quarry.

The island’s first quarrying might have started as early as the 19th century. It was reported that about 3,300 tons of granite were shipped from Pulau Ubin to mainland Singapore in 1910.

The Ubin granite, over the decades, had been used extensively for the building of public flats, roads and canals, as well as many local landmarks such as the Horsburgh Lighthouse, Raffles Lighthouse, Istana and Paya Lebar Airport. The construction of the Causeway and Sembawang Naval Base, in the 1920s and 1930s respectively, made use of the granite supplies from both the Pulau Ubin and Mandai quarries (Mandai Quarry, Seng Kee Quarry and Resource Development Corporation Quarry).

Ketam Quarry, otherwise known as Aik Hwa Quarry, was in operation between 1964 and 1999. Producing almost 180 tonnes of granite every month, it made up 30 to 40 percent of Singapore’s demand for the construction and reclamation projects. At its peak, the company hired more than 100 workers, many of them residents of Pulau Ubin. When the quarry shut down in May 1999, many of its staff chose to retire. Others remained on the island as fishermen, farmers and shopkeepers.

Pekan Quarry was another quarry on Pulau Ubin, formerly named Ho Man Choo Quarry. Located at the middle of the island, it was renamed as a reflection of its proximity to Pulau Ubin’s main village (pekan refers to “town” in Malay). After its closure, its two quarry pits were filled up with rainwater, and merged to form a scenic lake. A lookout point at the top of the quarry was built in 2007, and has been popular among the visitors.

The Pulau Ubin quarries ceased their operations after the granite had been mined to below sea level. Some of the pits were as deep as 40m. The island’s quarries were shut down one after another by the nineties. Ketam Quarry was the last surviving quarry until 1999. With the departure of the quarry workers, the population of Pulau Ubin dwindled from 1,200 in 1980 to about 400 by 1995.

The quarries, abandoned for years, have been gradually reclaimed by nature. Lush greenery and thick vegetation surround the pits that have been filled with rainwater, and become new homes for different species of birds and fish.

In April 2007, however, due to the disruption of granite supply from Indonesia, Kekek Quarry was reopened for limited quarrying works.

Dangers and Risks

Besides the tough manual work, the workers at the granite quarries were constantly subjected to high risks, particularly before the sixties when the concept of safety was often neglected or not taken seriously. Every year, there were dozens of reports of quarry workers killed by plunging rocks, falling off the cliffs or dynamite explosions.

Working conditions in the sixties and seventies remained extremely poor for the quarry workers. The work sites often suffered serious air pollution that was made up of white granite powder in the air produced by the blasting and grinding operations. Many quarry workers simply used towels to cover their faces, even though masks were provided by their companies.

By the early seventies, silicosis – a lung disease caused by inhaling silica dust – had became the chief disease among industrial workers. The quarry workers were especially affected due to the nature of their jobs.

Other Quarries

While there were granite quarries at Bukit Batok, Bukit Timah, Mandai, Jurong, Choa Chu Kang and Pulau Ubin, Tampines and Loyang were better known for their sand quarries. The Tampines sand quarries were started as early as 1912, but the sand quarry boom occurred much later – during the sixties – when sand was in high demand due to the development of many areas in Singapore.

At its peak, Tampines had more than 20 sand quarries. Many farmers and fishermen in the vicinity, attracted by the booming industry, joined to become sand quarry workers. The sand quarrying eventually stopped in the later years, and one of the quarries, the Tampines Quarry, was filled up with water to become a lake today.

Published: 30 July 2017

Updated: 05 June 2019

Could I check if the Seng Kee Quarry and Seng Chew Quarry are accessible?

Seng Chew Quarry is accessible but please be very careful as the water in the quarry is very deep especially after a heavy thunderstorm

Oh, that is great! You do seem to be someone knowledgeable about quarries in Singapore. I am actually doing a small research project on quarries in Singapore, specifically the Bukit Timah area. Is there any way that I can contact you privately?

Hi, you can send an email to yesterdayom@gmail.com 🙂