Futsal enthusiasts would be familiar with Jalan Benaan Kapal. But for others, even those who frequently visit the Singapore Indoor Stadium, Leisure Park Kallang or Decathlon (Kallang), it is easy to miss this quiet stretch of road.

Jalan Benaan Kapal was constructed in the mid-sixties, located at the edge of the former premises of old Kallang Airport. On its opposite, separated by Sungei Geylang, were Kampong Kayu Road and Kampong Arang Road, an area well-known for their charcoal/firewood businesses and twakows/tongkangs repair shops between the fifties and eighties.

In the early sixties, the Singapore government planned to expand the shipbuilding, ship repair and marine engineering industries. Sungei Geylang, with its suitable width and depth, was one of the choices for the upcoming industry. The former Kallang Airport had closed in 1955, and the vicinity had been converted into a recreation park reserved for future redevelopments.

In 1963, a section of the Kallang Park, along Sungei Geylang, was made available. Within a couple of years, some 22 shipyards and 19 workshops of various sizes set up their businesses here. A road called Jalan Benaan Kapal – its name means “ship building road” (kapal refers to ship and benaan (binaan) is construction in Malay) – was built to provide better accessibility to the firms and its workers. The area also became known as the Shipyard Row.

In 1967, local ship repair and engineering giant Eagle Engineering Co. Ltd invested in a new dry dock and slipway at Jalan Benaan Kapal. Designed and constructed by local engineers and technicians, the dock and slipway could accommodate ships of up to 200ft (61m) in length and 1,000 DWT (dead weight tonnage), and enable repair works to be carried out in dry conditions. Opened by former Finance Minister Lim Kim San, the new facilities were hailed as a major milestone in Singapore’s progress in the ship repair and marine industry.

Beside their $500,000 investment in the dry dock and slipway, and a further $1 million in new machinery, Eagle Engineering also built two $150,000 buildings at Jalan Benaan Kapal. This equipped their 300 workers to operate round the clock for the ship inspections, servicing and repair works. Just a month after the completion of the dry slipway, the company received their first customers for ship inspection and servicing. They were the Slamet Tiga, a 840 DWT Norwegian tanker, and La Ponda, a 667 DWT Indonesian cargo vessel.

The thriving industry and large number of workers meant that food would be in great demand. Hence, by the late sixties and early seventies, Jalan Benaan Kapal was lined by rows of street hawkers selling various kinds of local food and drinks. The increasing poor hygienic conditions and clogged drains at Jalan Benaan Kapal became a concern, prompting the Public Health Division to send officers there to educate the hawkers in proper food waste disposal.

A small canteen also emerged to cater for the daily needs of the shipyard workers. Built in 1968, it has 10 stalls offering drinks, noodles, nasi lemak, mee rebus and others. The small food venue, popularly known as Jalan Benaan Kapal Hawker Centre, continues to survive today. Seems to be forgotten in the passage of time, the food centre is among some of the remnants left behind after the industry in the vicinity had closed and relocated in the mid-eighties.

Besides concerns of poor hygienic conditions, safety and security were also issues for the companies at Jalan Benaan Kapal. Break-ins were not uncommon, and news of thefts often hit the headlines in the newspapers. In 1973, there was also a serious explosion incident at one of the warehouses, resulting in one death and a dozen injuries. The incident was investigated and later determined to be caused by illegal explosives brought in by one of the coppersmiths, ruling out a work-related safety lapse.

Jalan Benaan Kapal’s ship repair firms, in the early seventies, came under the management of the Jurong Town Corporation (JTC) which was branched out from the Economic Development Board (EDB) in 1968 as a specialist agency for Singapore’s industralisation.

In the mid-seventies, however, the shipyards were concerned by the government’s plan to link Tanjong Rhu to the City, which would cut off Kallang Basin from the sea and turn it into a storage reservoir. The authority even went to the extend to study the feasibility of a drawbridge in order not to disrupt the maritime traffic at the basin and Kallang and Geylang Rivers.

But the uncertainty was enough to put many Jalan Benaan Kapal companies to shelf their expansion plans, as a low level bridge or link between Tanjong Rhu and the city area would block the larger vessels from entering the Kallang Basin and their facilities. Prior to the rumours, several shipyards at Jalan Benaan Kapal had planned to upgrade their docks to accommodate ships of up to 2,000 DWT.

The link did take place in 1981 in the shape of the tall majestic Benjamin Sheares Bridge, part of the East Coast Parkway (ECP), that connect Tanjong Rhu to the city. The once narrow strip of Tanjong Rhu was vastly expanded through land reclamation in the seventies, allowing the construction of the ECP. At the site of the former Kallang Airport runway, a new National Stadium was constructed and completed in 1973, making Kallang a major sporting venue in Singapore.

But it was not the bridge nor the nearby redevelopment projects that led to the downfall of the ship repair industry at Jalan Benaan Kapal. In the late seventies, the Singapore Government embarked on a massive project to clean up the polluted water passageways in the city area, including the Singapore River, Kallang Basin and Sungei Geylang.

The charcoal and firewood trading firms and bumboat repair workshops at Tanjong Rhu, which had flourished for more than two decades, were among the first to be affected. Due to their heavy pollution to the Geylang River, they had to be phased out and demolished.

The Jalan Benaan Kapal ship repair companies, on the other hand, were given the choice to merge into larger shipyards, so that they could pool the resources and reinvent themselves with cleaner and more efficient work systems that comply to the Ministry of Environment’s new set of stringent anti-pollution measures. Otherwise, they would have to be relocated to other sites at Jurong, Woodlands or Senoko.

The companies – many of them were family businesses – rejected the merger proposal in 1982. As their leases would be expiring in mid-1983, some agreed to relocate their trades to the new premises at Penjuru Lane, along Sungei Jurong. Others chose to cease their operations and shut down the businesses. By the mid-eighties, the glorious days of Jalan Benaan Kapal’s Shipyard Row were no more.

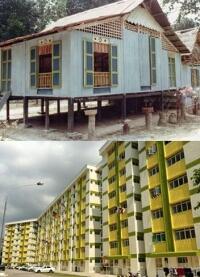

What were left behind are the little hawker centre, shophouses and the former buildings of warehouses and workshops. In the mid-2000s, the vacant buildings were given a new lease of life. Named The Cage, they were refurbished, painted with bright colours and converted into futsal courts.

Since then, many young futsal lovers have visited this place and utilised the facilities, but perhaps only a few will know that Jalan Benaan Kapal was once the pioneering ship repair and servicing hub of Singapore.

Published: 07 September 2020

I don’t know how long will the little hawker centre will last. If you are in the area, feel free to drop by and support the stallholders.

Not to mention they have one of the most affordable kopi/teh in Singapore, at only 60-70c!

A beautiful piece of history preceding the old national stadium. Thank you for sharing and reminding us.

Jalan Benaan Kapal, brought a lot of memories. My late dad leased one of the factory lot( those now painted in red) opposite of the shipyards in 1968 from JTC and returning it when the lease expired in 1998. The small factory casted molds and parts supplying to the shipyards. I had spent a lot of time there in the 70s before and after school. ( in the 70s we had afternoon session)

I knew at Jalan Benaan Kapal there was a shipyard. I drove passed, on the way to the hawker centre. In mid 1974 the hawkers were without water and electricty supply within their stalls. There was a common wash area with a water stand-pipe fronting the hawker centre. On the opposite side of the drive way was a block of double storey shophouse The shops catered to the shipyard, selling bolts and nuts, ropes, paints, pulleys, anchors, etc. The upper floors lived Myamar migrant workers who worked at the shipyard.