Not many people are aware that there is a Japanese cemetery in Singapore, situated in the middle of a high-end residential estate along Chuan Hoe Avenue, off Yio Chu Kang Road. Probably to avoid in stirring up any bad memories of the older Singaporeans whose forefathers had suffered or perished during the Second World War, there is little publicity of the cemetery park.

The Japanese Cemetery Park was established in 1891 as a burial ground mainly for the Japanese merchants and prostitutes that had lived in Singapore in the late 19th century and early 20th century. It was then a chaotic period in the eastern Asia, where the Empire of Japan, in the midst of Meiji Restoration, underwent rapid modernisation and military expansion. In a space of 30 years, it had defeated Qing Dynasty (1895) and Russian Empire (1905) in major battles, and had annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom (in 1879), Taiwan (1895) and later, Korea (1910).

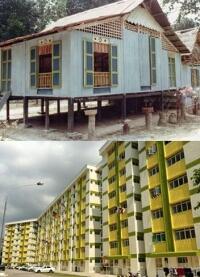

Occupying a land-size of 7 acres (more than 28,000 square metres), it was the largest Japanese cemetery in Southeast Asia. The land was donated by three brothel owners Futaki Takajiro, Shibuya Ginji and Nakagawa Kikuzo, who also owned rubber plantations in the vicinity. The request of building a Japanese cemetery was approved by the British colonial government on 26 June 1891, and its management was handed by the Japanese-run Mutual Self-Help Society.

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the majority of the Japanese population in Singapore was prostitutes, or karayuki-san, from the rural prefectures of Japan. They mostly plied their trades at Boon Tat Street (near Telok Ayer Market) and Malay Street (near present-day Bugis), which was the reason why these two streets were given colloquial names of “ji poon koi” (Japanese Street) in the older days.

Initially, almost half of the tombstones at the cemetery belonged to those Japanese prostitutes who never made it back to Japan. After the First World War, as more Japanese merchants and traders arrived at Singapore, the Japanese population generally became more well-off. Many of the merchants and traders, after their deaths, were buried or cremated at the cemetery with detailed and elaborated tombstones and memorial plaques.

The cemetery came under the control of the Japanese forces after the fall of Singapore. A Shonan Patriotic Service Association was established to be in charge of all burial services of the Japanese military casualties. When Japan surrendered in 1945, the soldiers who committed suicide or executed were also cremated here. Many memorials were erected; one of the most famous belonged to Field Marshall of the Japanese Forces in Southeast Asia Hisaichi Terauchi (1879-1945).

When the British returned after the end of the Second World War, they repatriated the entire Japanese population in Singapore. No Japanese was allowed to return to Malaya until the signing of the peace treaty in 1951. With neglect and lack of maintenance, the cemetery soon fell into disrepair. It was not until 1952, when Ken Ninomiya, the first Japanese Consul-General posted to Singapore after the war, requested a search for the war remains.

By then, the identifications of the dead were almost impossible as all the remains and ashes were enshrined together. Moreover, the efforts in the erection of the various memorials were also appreciated by the Japanese government, who decided to fund the restoration of the cemetery instead.

One of the most famous person to be buried in the cemetery was Yamamoto Otokichi (1817-1867), recognised as the first Japanese resident of Singapore. Otokichi’s life was filled with adventures, started at age 14 when he went sailing to North America. The Japanese crews were captured by the native tribe, but were rescued by a British trader John McLoughlin, who later brought them to England.

In the 1830s, Otokichi wanted to return to Japan but was rejected by the Tokugawa Shogunate. He then travelled to Macao and other parts of East Asia before settling at Singapore as a British citizen. By then, he had changed his name to John Matthew Ottoson, married a Eurasian lady called Louisa Belder and converted to Christianity. When he died of tuberculosis in 1867, Otokichi was first buried at Bukit Timah Christian Cemetery, and then moved to the Japanese cemetery. In 2005, his ashes were retrieved and brought back to Onoura, the hometown where he had left more than 170 years ago.

In 1969, the Singapore government handed the ownership of the cemetery back to the Japanese Association, which was originally the caretaker of the cemetery since 1917. In exchange for 2 acres of land in the vicinity, a Japanese school was built in Clementi at the request of the association. By 1973, no further burials were accepted by the cemetery, as part of the government’s plan in limiting the expansion of the 42 cemeteries islandwide. Saiyuji (Temple of the West), the main shrine of the cemetery with a history dated back to 1911, was given a restoration in 1986. A year later, the cemetery was officially renamed as Japanese Cemetery Park.

Published: 09 July 2013

Updated: 28 July 2017

The Japanese cemetery in the mid-1980s, before its restoration and renaming as Japanese Cemetery Park

(Photo Credit: National Archives of Singapore)

A neat article…

http://news.asiaone.com/news/singapore/ghost-town-roads

SECRET JOURNEYS SINGAPORE

Ghost-town roads

Yio Chu Kang, with its Japanese cemetery, remains elusive to David Ee

David Ee

The Straits Times

Sunday, Aug 11, 2013

SINGAPORE – When I was a boy, if prata was on the dinner menu, there was only one place to go – Jalan Kayu.

The ramshackle lane in the north-east in Yio Chu Kang has long been a favourite with Singaporeans as the place to eat roti prata, after roadside eateries sprang up there when the British built the Seletar airbase in the 1920s.

But for me two decades ago, the lane existed in my imagination as a solitary place secreted away, found only in the deep of night.

Delirious with expectation, we would pile into the family car at night and head off. The road name would flash by as we exited the Tampines Expressway, conjuring up images of greasy delights in what felt like a “cowboy town” far away.

Even today, Jalan Kayu, and indeed Yio Chu Kang, retains this aura of remoteness. The area remains elusive to me and perhaps to many more Singaporeans.

Ask people to point out Yio Chu Kang on a map, and I wonder how many can. Its namesake road meanders from Upper Serangoon Road to Upper Thomson Road, sandwiched between Ang Mo Kio and Hougang.

At 9.4km, it is perhaps the country’s longest road (if you consider Bukit Timah and Upper Bukit Timah roads as separate entities). But it has no eponymous mall. No “hub”. Its MRT station delivers you into a maze of nondescript Ang Mo Kio avenues.

Chances are, you drive down Yio Chu Kang Road and chart your position by the new towns that cloister it. But trail off either side and at last the elusive suburb begins to emerge, the one that only its denizens tend to know. Even if, as I discover, they too struggle to articulate their geographical bearings.

Across the road from Serangoon Gardens, ringed by crammed suburbia, is a Japanese cemetery that has been there since the late 19th century.

It is the final resting place for early Japanese, including prostitutes, who made Singapore their home, as well as war dead from World War II.

A prayer hall takes pride of place, and bougainvillea trellis corridors and an old lychee tree have drawn residents seeking rest alongside the dearly departed. Students turn it into a study spot. Others simply nap under the hall’s gently curved eaves.

I come across local resident Chester Tan as he walks home. The 20-year-old remembers running around the tombstones as a child with his cousins on the Mid-Autumn Festival night, lanterns and sparklers aglow.

Where does he tell people he lives, I ask. “Serangoon.” He shrugs. “They wouldn’t know if I said Yio Chu Kang. The road is just one whole stretch, it doesn’t seem like a place.”

Today, he is not headed to the cemetery but a nearby exercise area. “There’s nothing to do there. Just look at things.” His friends, he says, think likewise.

Other residents feel the same way about Yio Chu Kang as a whole, where the nearest mall can seem an endless bus ride away.

But others, with years behind them and memories of a gentler time, love precisely that dearth of “purpose” they find here.

When Madam Jamie Pang and her husband opened Seletar Hill Restaurant at Jalan Selaseh in 1991, she thought the area so ulu (Malay for remote) that she replaced its glass doors with wooden panels so she wouldn’t have to stare out at its “ghost-town” roads all day.

More than two decades later, it is its very “ulu-ness” that keeps her here, especially as her family lives in hectic Ang Mo Kio Central.

“We spend more time here than at home,” she says. Her favourite drive from home takes a detour down the Thomson end of Yio Chu Kang Road. “It’s just trees all the way,” she says.

I know what she’s talking about. One mesmerising stretch of road, just beyond the right turn to Jalan Kayu, opens up into a majestic boulevard. Giant Khaya trees with trunks the width of small cars line the central divider.

In our greener-than-green “City in a Garden”, we sometimes fail to see the trees for the forest. Here, you cannot but notice them, dwarfing all of modernity beneath them.

At Jalan Selaseh late on one rare chilly evening, a chatty grandma tells me how, back in the old days, British airmen from the nearby airbase would gather for drinks at the now long-gone Chusan bar. They would stock up at the provision store her late husband ran.

Today, while the Brits have gone, a provision store remains on the lane. Regulars down pints at The Lazy Lizard next door.

Little, it seems, has changed, even as it has. But as with elsewhere in Singapore, changes are evident and everywhere.

No one but the residents might remember, but where the spanking new Greenwich Village condo-mall hub now stands, there used to be a beloved wet market and food centre.

All the old-timers I speak to detest the new pretender, which smugly masquerades as the “village” store it unceremoniously replaced (across the road, an upcoming condo swankily touts itself as The Topiary).

But none question it, and all dutifully eat at its cookie-cutter, over-priced food court, and find newer, yet already familiar comforts in Gong Cha, Toast Box and Awfully Chocolate.

“It’s possible that in 50 years, all this greenery and ulu-ness may be gone,” says retiree Lee Boon Kee, who lives on a quiet cul-de-sac near Upper Thomson.

I can still see the old kampung road, now overgrown, skirting the adjacent forest. Rambutan and durian trees still stand where the kampung used to be. And residents, he says, still venture into the forest from time to time to harvest fruit.

A cement-mixer roars past, heading to a nearby construction site.

The nearby former clubhouse of the Singapore Teachers’ Union is being re-developed into a condo, he says. His next-door neighbour is doing much the same, adding extra floors to tower over the modest terrace houses.

As storm clouds gather, I make haste to a cafe I frequent. It is one of my favourite places in the area, I realise as I walk, along with the Japanese cemetery park and the Seletar Hills estate with its wide boulevards. Except that the cafe probably technically lies in Thomson, while the cemetery, according to Chester, is in Serangoon. And Seletar Hills estate, well.

Where does all this leave Yio Chu Kang? For a district boasting a road so long, it remains a nebulous one but refreshingly so.

In order-obsessed Singapore, where most things have their exact place and purpose, it is telling when a place appears not to be that, and not to matter.

Jalan Kayu, when I think of it now, is located just where it is.

No one really needs to know exactly where Yio Chu Kang is. But go there and you’ll discover it.

Just don’t expect to find much to do, which is much the point of the place.

Singapore’s Japanese prostitute era paved over

18th June 2005

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/

Clean, safe and green, Singapore is one of the most favored destinations for modern Japanese women who want to work and play hard.

In Japan, women often find it difficult to get into key corporate positions and face pressure to quit once they get married or give birth. So the city-state’s female-friendly working environment is quite attractive to them.

“In Japan, it’s almost impossible for women aged over 30 to find a full-time position. But it’s easier to get one here,” said Mayo Omura, a 32-year-old accountant at the local unit of Hewlett-Packard Co.

She and many other Japanese women interviewed for this article seemed well-informed about present-day Singapore — who to speak to for business, where to go for leisure, and what to buy at which shops.

What an overwhelming majority of them don’t know about Singapore, however, was the countless Japanese women who worked here as prostitutes between the late 19th century and early 20th century, women who were referred to simply as “Karayuki-san.”

“I suspect the days of Karayuki-san have become distant history,” said Kazuo Sugino, secretary general of the Japanese Association in Singapore.

Karayuki-san were Japanese peasant girls — mostly from the Shimabara Peninsula in Nagasaki Prefecture and Amakusa Islands in Kumamoto Prefecture — who were sold into the flesh trade in colonial Singapore and other parts of Southeast Asia.

Japan, the world’s second-largest economy, was a poor country a century ago, and women were one of its major exports, along with silk and coal.

Karayuki-san, together with other Japanese women who served as prostitutes elsewhere, including Siberia, Hawaii, Australia and some parts of India and Africa, were said to be the third-biggest foreign currency earner for Japan at the turn of the 20th century.

The existence of Karayuki-san in Singapore dates back to 1877, when there were two Japanese-owned brothels on Malay Street with 14 Japanese prostitutes, official Japanese data show.

Malay Street and the nearby streets of Malabar, Hylam and Bugis later grew into a big red-light district.

Singapore’s official records suggest 633 Japanese women were operating in 109 brothels in 1905. The number is believed to have been well over 1,000, if unlicensed prostitutes are included.

Combined with the far larger Chinese-dominated red-light district and other similar districts catering to different ethnic groups, Singapore was known as one of the centers of the sex industry in Asia in those days.

As Singapore started to develop around the 1870s, immigrants — mostly men — rushed in from China and India to toil at rubber plantations and tin mines or as rickshaw pullers. To maintain social order, British colonial rulers tolerated prostitution at designated brothels, bringing in Chinese and Japanese women in droves.

As Japan’s international profile rose with victories in the Sino-Japanese War in 1894, the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 and its having sided with the victors of World War I, Japan began to view Japanese prostitutes working overseas as a national shame.

In addition, successful Japanese business operations in British-ruled Malaya, now Malaysia, lessened the need for foreign currency earned by Karayuki-san. So the then Japanese Consulate General in Singapore banned Japanese brothels in 1920.

Consequently, many Karayuki-san were forcefully repatriated to Japan. But many others managed to stay in Singapore or move to other parts of Malaya, illegally selling themselves.

Four decades later, a young Japanese woman who settled here after marrying a Singaporean one day encountered a former Karayuki-san by chance and was shocked to learn about the tales of Japanese women working abroad.

“I was saddened to realize that I had known nothing about Karayuki-san,” said Yuko Gan, who later became a charismatic tour guide well-versed in Singapore’s history.

She has since found more former Karayuki-san, listened to them and told the stories of their lives to Japanese tourists.

“I believe I grew as a human, thanks to the encounter with former Karayuki-san. Thinking about their plight fills me with courage,” she said. “Up until 15 to 20 years back, four or five former Karayuki-san survived in Singapore. But not any more.”

Gone with the Karayuki-san is the Japanese red-light district. Ironically, the entire district is now a giant commercial complex that houses a department store run by Seiyu Ltd. and a shopping center operated by Parco Co., both Japanese companies.

Malay, Malabar and Hylam streets remain, but they are now merely passages under the roof of a structure called Bugis Junction, a popular spot with young Singaporeans that also houses movie theaters and the Hotel Inter-Continental.

Traces of Karayuki-san are more evident at Japanese Cemetery Park, where countless — and largely nameless — Karayuki-san are buried along with other Japanese.

Rumiko Motoyama, a 37-year-old bridal consultant who spent her early teens in Singapore, came back in the late 1990s to what she calls her “second hometown.” She visits the cemetery every summer during Bon, the Buddhist festival for the dead, to pay tribute to the deceased Japanese in Singapore, including Karayuki-san.

“I respect the Karayuki-san. They lived hard in unfamiliar places where they couldn’t understand local languages. They must have been so strong,” she said.

“As a Japanese living in Singapore, I’m grateful to the Karayuki-san, because I feel their hardships form a cornerstone in my mind on which I can live happily now,” Motoyama said.

This year, which marks the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II, is a good opportunity for Japanese to hark back to the past and look to the future.

One can draw a lot of lessons by taking a glance at the history between Japan and Singapore, especially Japan’s 1942 invasion and occupation up to 1945.

Ordinary Japanese know little about the killings of ethnic Chinese in Singapore by the Imperial Japanese Army during the war years.

Sugino of the Japanese Association wants Japanese to face up to history involving their own country and other parts of Asia in order to strengthen friendly ties.

“It is important that those planning to live in Singapore from now study the present and past of Singapore and develop a clear understanding of Singapore, including Karayuki-san and the war,” he said.

Where is the exact location off Yio Chu Kang

I m a resident of Seletar Est. for more than 40 years. I have not heard of this Japanese Cemetry. Can u pls let me know the exact location for me to visit this historical site of Singapore.

NG ENG HUA

Tel: 96-250337

Hi, the address is 825B Chuan Hoe Ave, 549853

(Source: Google Map)

Wanna recce…

Roland Schoon remembers the Japanese Cemetary very well as I used to live in Rosyth Road. As a youngster I and my friends used to play ‘hide and seek’ and ‘paper chase’ at night in the area.good old days never to return.i am 87 years old and would welcome any news from friends still around.

COMMENT: Should the ashes of Japanese war criminals in Singapore cemetery be removed?

Yahoo News Singapore 18 July 2017

In a tranquil neighbourhood near Hougang lies a 126-year-old cemetery with a grim past etched on a granite pillar. Measuring less than a metre in height, the pillar marks the final resting place of 135 Japanese war criminals.

These war criminals were executed in the former Changi Prison for committing atrocities in Singapore during World War II, such as the Sook Ching Massacre. Their ashes ended up being buried in the Japanese Cemetery Park at 825B Chuan Hoe Avenue, with the memorial for them paid for by the Japanese government in 1955. The Japanese inscription on the pillar describes them as martyrs.

Another pillar at the park marks the burial spot of 79 Japanese war criminals who were hanged in then Malaya. A separate memorial contains the ashes of 10,000 Japanese war dead collected from two bygone Shinto shrines in Bukit Batok and MacRitchie.

At the other end of the park is the tombstone of the most senior-ranking Japanese commander who fought in the Southeast Asia theatre of war. Field Marshal Count Hisaichi Terauchi, the Supreme Commander of the Japanese Expeditionary Forces in the Southern Area, also happened to be a suspected war criminal. Terauchi died in Johor in 1946 while the British were still investigating his alleged war crimes.

On any given day, a small number of mostly Japanese tourists and Singaporeans would visit the park to place flowers and burn joss sticks for the dead.

The continuous presence of the ashes of war criminals over the decades at the cemetery, declared as a memorial park by the Singapore government in 1987, is perplexing. With the 30-year lease of the park ending in 2019, there should be a discussion about the future fate of the ashes.

Should the ashes be repatriated back to Japan for reburial? Another option can be gleaned from the immediate period after the war, when there were intense debates among British officials over what would happen to the ashes of Japanese war criminals. According to one source, the authorities in Singapore sometimes would burn the corpses of war criminals and dispose the ashes at sea to prevent them from being honoured at a gravesite.

The repatriation of the remains of Japanese war criminals would be consistent with a longstanding policy of the Japanese government. Addressing both houses of the Japanese parliament in February 2015, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said, “I will work to ensure that the remains of Japanese soldiers, many of whom still remain resting in other countries, are repatriated as quickly as possible.”

The Syonan Gallery debacle

The park is not just a burial ground for Japanese soldiers and war criminals. Built in 1891 by three Japanese brothel owners, the cemetery was originally populated by the remains of mostly young Japanese prostitutes working in Singapore. It also houses the remains of Japanese civilians who had lived here. In all, there are 910 tombstones at the park, which spans about 30,000 square metres.

Nonetheless, it is the military aspect of the park that is controversial. The majority of Singaporeans today may not be able to relate to the harsh realities of life under the Japanese Occupation but for wartime survivors, the wounds still run deep.

In February, the Singapore authorities unveiled a new exhibition called Syonan Gallery: War and its Legacies at the former Ford Factory, where the British forces surrendered to the Japanese on 15 February 1942. The exhibition’s name was in reference to the renaming of Singapore to Syonan-to by the occupying Japanese forces.

Many Singaporeans, including civilian survivors of the war, protested against the name given the anguish and suffering of the country’s wartime generation. The controversy prompted the exhibition to be renamed Surviving the Japanese Occupation: War and its Legacies. Minister for Communications and Information Yaacob Ibrahim did the right thing by apologising to Singaporeans about the original naming just two days after the launch of the exhibition.

Puteh Mahamood was just 11 years old when Singapore fell to the Japanese. Speaking to Yahoo News Singapore in Malay recently, Puteh said he had to stop schooling to support his family and life was hard under the “heartless” Japanese military authorities.

One day, a boy stole from a store that Puteh was working at, and was captured by Japanese soldiers. The boy was taken away to the old YMCA building, where the headquarters of the Japanese secret police Kempeitei were located, and was never heard from again, Puteh said.

When told about the burial spot of the war criminals at the park, Puteh, now 86, expressed surprise that it exists. “The war criminals’ ashes should be brought back to Japan for reburial so that their souls can rest in peace,” he said.

A war memorial service at the park?

Kazuo Sugino, the former Secretary-General of the Japanese Association of Singapore, which has been managing the park since 1969, said the Singapore government has agreed in principle to a lease extension.

In an interview with Yahoo News Singapore on Monday (17 July), Sugino claimed that most of the ashes of the war criminals had been sent back to Japan many years ago. While Sugino acknowledged the “sensitive nature” of the military memorials, he stressed that the park’s history should not be overshadowed by what happened during the war.

“The cemetery is not just for the military dead. The majority are (the remains of) civilians. The Japanese community’s history is reflected at the park. We feel it is important to learn about it,” Sugino said.

Yahoo News Singapore has sent queries about the status of the cemetery as a memorial park to the National Heritage Board and has yet to receive a reply on the park’s status and the agency in charge.

If the Singapore authorities were to formally agree to the lease extension and the ashes of the war criminals remaining at the park, the Japanese community can consider commemorating the occupation years, in part as a sign of appreciation for the park’s continuous presence.

A memorial panel can be erected at the park to chronicle the war crimes committed by Japanese soldiers in Singapore. This is pertinent as many visitors to the park are Japanese, whose post-war governments have angered several Asian countries over the decades for their repeated attempts to whitewash Japan’s wartime history.

Past commemoration services to mark the Fall of Singapore were typically held annually at the Civilian War Memorial and the Kranji War Memorial in remembrance of the civilians and Allied military personnel, respectively, who lost their lives during the war. Crucially, these services overlooked the poignant symbolism of the belligerent that started the war. As such, a similar service can also be held at the park every 15 February to hope for peace to be sustained in Singapore and the broader region.

The erstwhile Syonan Gallery triggered a fierce national debate about the Japanese Occupation over a name. But an even more potent symbol of the brutal occupation, in the form of the ashes of war criminals, merits a separate discussion among Singaporeans, the Japanese community and the authorities.

An extension of the lease of the park beyond 2019 would exemplify the postwar spirit of reconciliation between Singapore and Japan. Such a decision, however, should not be undertaken at the expense of educating the current and future generations of Singaporeans and the Japanese people about the war at the very burial spot of the fallen who were part of an invasion force responsible for the deaths of as many as 50,000 civilians in Singapore.

– translation of interview with Puteh Mahamood by Safhras Khan

https://sg.news.yahoo.com/comment-ashes-japanese-war-criminals-singapore-cemetery-removed-041516752.html

Thank you for this very informative and well researched article. It was mentioned that Taiwan was annexed by Japan in 1845. It is only in the Treaty of 1890 that the Qing Government handed Taiwan over to Japan. The colonisation of Taiwan by Japan then last till the end of the Pacific theatre of WWII.

Thanks for pointing out the typo error. Qing ceded Taiwan to Japan in 1895 after its loss in the Sino-Japanese War.

Chuan Hoe Avenue was often known as “jit boon tiong” (日本塚) by the residents living in the nearby kampongs in the past.