Located along Balmoral Road at the prime district 10 vicinity, Sloane Court Hotel became the latest hotel in Singapore to end its business. It was recently acquired by Tiong Seng Holdings and Ocean Sky International for $80 million; its site is expected to be developed into a 12-storey, 80-unit condominium.

The humble hotel, which began in 1962, was initially plain-looking, as it was used as a 26-room boarding house exclusively for British soldiers and their contractors. However, when the British armed forces pulled out of Singapore in the early seventies, the hotel had to open up to a bigger market for its business to survive.

Some of its guests in the seventies included Indonesian and Thai businessmen, and Japanese engineers, who were hired to come to Singapore to develop the Jurong industrial estate.

In the late seventies, the hotel’s Hainanese owners, a Chiam family, decided to give the hotel’s facade a facelift. They sought opinions from Stanley Foster, a family friend and Englishman who had opened a smokehouse named Fosters at the Cameron Highlands. The Chiams eventually chose the Tudor style due to its timeless and classic nature, and it became the iconic feature of the hotel until now.

Stanley Foster also helped the Chiam family in naming the new-look hotel Sloane Court. Inspired, the Chiams went on to open two more Tudor-style houses serving food and drinks – Pavilion and Tangle Inn – although both did not survive past the eighties.

Beside the Tudor-style colonial building, another attraction of Sloane Court Hotel was its Berkeley Restaurant, which served traditional Western cuisine in Hainanese style. Some of the restaurant’s best-known specialties were its English Porterhouse steak, Penang-style Inche Kabin chicken and English devilled chicken, which was cooked in mango chutney with a touch of white vinegar.

The caterers managing Berkeley Restaurant also owned other eateries in the eighties – the Captain’s Cabin at Serangoon Gardens and Balmoral Steak House at Holland Road.

The hotel was later renovated to expand to 32 rooms, and its old English charm continued to attract many guests, among them European tourists, especially the British, and Singaporeans who had studied or lived in Britain, well into nineties. Its relatively low room charges and short distance away from the booming Orchard Road shopping belt also played a big part in its positive occupancy rate.

Singapore’s first hotel was started as early as 1839, 20 years after the founding of Singapore. Opened by a British businessman called Gaston Dutronquoy, the hotel, known as London Hotel or Dutronquoy’s Hotel, was located between High Street and Coleman Street, and had rooms, restaurants, theatre and a photography studio.

The Colonial Hotels

Singapore experienced a tourism boom in the late 19th century and 20th century. Many hotels, particularly the luxury ones, were built during this period. Some have flourished till this day, such as the Raffles Hotel (since 1887) and Goodwood Park Hotel (since 1929), which have cemented their legacies as Singapore’s iconic landmarks.

Other colonial hotels did not survive as long, and many had their businesses wounded up after decades of operation. Some of the renowned examples were Adelphi Hotel (1850s-1973), Grand Hotel de l’Europe (1857-1932), Hotel de la Paix (1865-1914), Bellevue Hotel (1901-1951), Caledonian Hotel (1904-1910s), Hotel van Wijk (1905-1931) and the old Sea View Hotel (1906-1964).

Before its closure in 1973, Adelphi Hotel was the oldest hotel in Singapore, claiming a history that had spanned more than 120 years. Today, that honour belongs to the Raffles Hotel, which just celebrated its 130-year establishment in 2017.

There were hundreds of hotels, large and small, established in Singapore since the 19th century. Some were well remembered and had left their marks in the history, while many others were forgotten.

Below were some of the iconic ones that were demolished in the past 30 years (the list of former hotels is not in any order).

Marco Polo Hotel, Tanglin Road (1968-1999)

Located at the junction of Tanglin Road and Grange Road, Marco Polo Hotel, or officially Omni Marco Polo Hotel, was a famous 10-storey 300-room hotel landmark built in 1968. It was owned by the Goodwood Group, and was first known as Hotel Malaysia when it was completed.

Well-known for its luxurious furnishings and high quality services, the hotel, by the eighties, was voted as one of the best hotels in the world. It became a top choice hotel for many foreign leaders and international celebrities during their stays at Singapore.

Many locals as well as tourists would also remember the iconic fountain at Tanglin Circus that formed a picturesque scene with the hotel. The fountain was built and commissioned in 1966 by the Public Works Department (PWD), but was demolished a decade later in 1977.

In the mid-eighties, the ownership of the hotel changed hands and Hotel Malaysia was renamed Omni Marco Polo Hotel in 1989. The owners, however, had to fold up the hotel business in the late nineties after its finances were badly affected by the Asian Currency Crisis. In 1999, Marco Polo Hotel officially walked into history, when it was demolished and replaced by a luxury condominium named Grange Residences.

Katong Park Hotel, Meyer Road (1953-2002)

Opened in 1953, the former landmark at Katong Park had many names – Embassy Hotel, Hotel Ambassador, Duke Hotel, and eventually Katong Park Hotel – before it made way for a condominium in the early 2000s.

First called Embassy Hotel, the hotel was officially opened on 26 April 1953 as a modern building that had air-conditioned rooms and other modern facilities. Also boasting to be the largest hotel in British Malaya after the Second World War, it had splendid views of Katong Park and the seafront.

The following decades saw the hotel’s ownership changed hands several times, first in 1960 when it was rebranded as Hotel Ambassador. The hotel was badly affected by the Konfrontasi crisis in late 1963, when Indonesian saboteurs set off explosions at Katong Park, causing its windows to be shattered by the strong blasts.

In 1982, Hotel Ambassador was renamed again, this time as Duke Hotel. The hotel was then sold and reopened as Katong Park Hotel in 1992. Like Marco Polo Hotel, Katong Park Hotel was dragged down by the Asian Currency Crisis. Its operations ran into deficit, and had to call it a day in 1998. A condominium called View@Meyer was built at its site in 2006.

Copthorne Orchid Hotel, Dunearn Road (1969-2011)

The six-storey Copthorne Orchid Hotel was first started in 1969 as Orchid Inn by local magnate and chairman of Hong Leong Group Kwek Hong Png.

The six-storey Copthorne Orchid Hotel was first started in 1969 as Orchid Inn by local magnate and chairman of Hong Leong Group Kwek Hong Png.

The hotel would later be renamed Novotel Orchid Inn before becoming part of the group’s Copthorne Orchid hotel chain in Singapore and Malaysia.

The hotel’s reddish facade was a once familiar sight along Dunearn Road. It had been frequently patronised by both local and foreign celebrities, and among the hotel’s long serving staff, the most popular topic was perhaps the marriage of Hong Kong star Chow Yun Fat and his Singaporean wife Jasmine Tan, who once worked at the hotel as a receptionist.

In 2011, Copthorne Orchid Hotel was closed after more than four decades of existence. It was subsequently demolished and replaced by a luxury freehold condominium called The Glyndebourne.

Oberoi Imperial Hotel, Jalan Rumbia (1971-1999)

Located at Jalan Rumbia, off River Valley Road, and just a short distance away from the iconic National Theatre, the former Oberoi Imperial Hotel started in the 1950s as a residential block to house the British military officers. It underwent extensive renovations in the late sixties and was converted into a luxury hotel that was officially opened in 1971.

The 13-storey hotel had more than 500 rooms, coffee houses, a swimming pool, lounge and three restaurants serving Chinese, Indian and international cuisine. Popular in the seventies and eighties, the hotel boasted a list of distinguished guests that included Tonga’s King Taufa’ahau Tupou IV.

The hotel was sold to the Hind Group in 1977 for about $37 million, and was renamed as Imperial Hotel. In the late nineties, the group announced plans to redevelop the hotel. By 1999, the hotel was demolished, and in its place, a new luxury condominium called The Imperial was erected in the early 2000s.

MayFair City Hotel, Armenian Street (1950-2000s)

The former Mayfair City Hotel (also known as Mayfair Hotel in its early days) was housed in two Art Deco-style shophouses at Armenian Street. The hotel was four-storey tall; its ground level was occupied by a restaurant, lounge and bar, while the second to fourth level were made up of 26 air-conditioned rooms that had two beds, bath tubs, teak furniture and radio relay speakers.

When the hotel was opened in 1950, it was fully booked by the Qantas Empire Airways-British Overseas Airways Corp (QEA-BOAC) to accommodate its crews. The hotel’s popularity peaked in the sixties, but by the seventies, it was no longer considered a luxury hotel. In 1971, its rooms ranged between $30 and $40 per night as compared to the $45 rate and above charged by other luxurious hotels.

In 1976, the hotel suffered from poor occupancy rate and had to close down, although its cocktail lounge and restaurant remained opened for business. Three years later, the hotel made a comeback under a new management team. The hotel then operated till the late-2000s. This time, it was shut down for good, and its premises was converted into a foreign worker dormitory. The shophouses were subsequently vacated in 2011 for renovation projects.

Great Southern Hotel, Eu Tong Sen Street (1936-1994)

The Great Southern Hotel, or popularly known as Nam Tin (Southern Sky in Cantonese), was a well-known landmark along Eu Tong Sen Street. Completed in 1936, the boutique hotel was the holder of many records, including the tallest building at Chinatown, and the first Chinese hotel to be equipped with a lift.

Housed in a building owned by Lum Chang Holdings, the Cantonese-themed Great Southern Hotel was largely catered to rich Chinese from China and Hong Kong. The elaborate hotel was six storeys tall, and featured shops at its ground level and a Chinese restaurant on its fourth floor. There was a tea house at its rooftop garden, and its fifth level was previously home to the famous Southern Cabaret nightclub.

The fifties and sixties were arguably the hotel’s golden era, when its popularity and high standards, particularly in its entertainment and services provided, earned a fine reputation as the “Raffles Hotel of Chinatown”.

In 1994, the Great Southern Hotel was converted into a department store called Yue Hwa Chinese Products, after the hotel was sold to Indonesia-born Hong Kong businessman Yu Kwok Chun (born 1951) for $25 million. The preservation of the hotel’s facade and unique features helped its owner win the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s (URA) Architectural Heritage Award in 1997.

Sea View Hotel (new), Amber Close (1969-2003)

The old Sea View Hotel, a nearby hotel of the same name, was a famous hotel in the first half of the 20th century, being dubbed as Singapore’s leading hotels along with Adelphi Hotel and Raffles Hotel. The hotel, located off Meyer Road, ceased its operation in 1964.

The new 18-storey Sea View Hotel was opened at Amber Close five years later in 1969.

Some of the memorable features of the new Sea View Hotel, well remembered by its former guests and the Katong residents, was its coffee lounge serving delicious Western food dishes and the unobstructed view of East Coast, before the land reclamation, at its highest floors.

Sea View Hotel was eventually closed down in 2003. Amber Close was expunged, and the site was redeveloped into a condominium named The Seaview.

Boulevard Hotel, Cuscaden Road (1973-2000)

Located at Cuscaden Road, the hotel was known as Cuscaden House Hotel before it was bought over in 1973 by Khoo Teck Puat (1917-2004), a well-known local banker and hotelier, and, at one point, Singapore’s richest man.

Located at Cuscaden Road, the hotel was known as Cuscaden House Hotel before it was bought over in 1973 by Khoo Teck Puat (1917-2004), a well-known local banker and hotelier, and, at one point, Singapore’s richest man.

The hotel was renamed Hotel Malaysia (there were two Hotel Malaysia in Singapore in the late seventies and early eighties) in 1975, and again to Boulevard Hotel in 1983 after a series of renovation works.

The Hong Leong Group bought the property for $410 million in 1997, and subsequently demolished the hotel in 2000 for the development of the Cuscaden Residences condominium.

Garden Hotel, Balmoral Road (1971-2009)

The Garden Hotel, designed like a courtyard with gardens and fitted with air-conditioned rooms and a large swimming pool, began its business in 1971 at a construction cost of $3 million. It was situated along Balmoral Road, just opposite of Sloane Court Hotel.

The hotel was bought over by the Chua family of the Cycle and Carriage in 1981, when they spent $25 million in an acquisition from Vun Lee Pte Ltd. In 1999, property developer City Development Ltd purchased the property for more than $100 million. The Garden Hotel continued to operate until 2009, when it was closed to make way for the development of luxury condominium Volari at Balmoral.

Lion City Hotel, Tanjong Katong Road (1968-2011)

Owned and operated by the family of Wee Thiam Siew, a local property tycoon, the 10-storey 166-room Lion City Hotel was opened at a cost of $4.2 million in 1968 at the junction of Tanjong Katong and Geylang Roads. The hotel caught up with the fast-growing tourism industry after Singapore’s independence, when there was a period of hotel shortage to meet the increasing demands.

On 2 August 1968, the Lion City Hotel had a grand opening officiated by Dr Goh Keng Swee, then-Minister for Finance. Modernly designed, the hotel, at its highest floor, offered a panoramic view of the city area. Its rates in the late sixties and early seventies stood at $30 and $40 per night for single room and double room respectively. A deluxe suit would cost $90.

In 2011, UOL Group bought Lion City Hotel and the adjoining former Hollywood Theatre, which had stopped screening movies since the nineties, for $313 million. Today, the site of the former hotel was occupied by OneKM Mall.

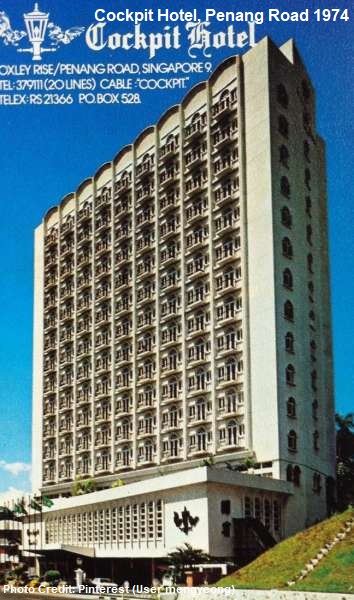

Cockpit Hotel, Penang Road (1972-1997)

Completed in 1972, the Cockpit Hotel was built at the former site of another luxury hotel called Hotel de L’Europe (not the same Hotel de L’Europe of the 19th and early 20th century).

Completed in 1972, the Cockpit Hotel was built at the former site of another luxury hotel called Hotel de L’Europe (not the same Hotel de L’Europe of the 19th and early 20th century).

The Hotel de L’Europe, established in 1947, became known as the Cockpit due to the frequent stays of the Dutch airline KLM crews and passengers.

Indonesian businessman Hoo Liong Thing started the new 13-storey 230-room Cockpit Hotel in 1972, but the hotel changed hands several times, first in 1980 and again in 1983.

It was sold a final time in 1996 to property developer Wing Tai, which ceased the hotel operation a year later. The building was then left vacated for a long period of time, leading to numerous paranormal stories about the “abandoned” hotel.

Today, a condominium called Visioncrest Residence stands at its site.

Century Park Sheraton Hotel, Nassim Road (1979-2004)

Located at Nassim Road, one of Singapore’s most expensive districts and near the Orchard Road shopping belt, the Century Park Sheraton Hotel was opened in 1979 as a luxury hotel.

The 465-room hotel was owned by the All Nippon Airways (ANA), which bought the property for $59 million in 1977 as part of the international Sheraton hotel chain. For years, the hotel was famous for its luxurious furnishings, Europa Ridley nightclub and the Cafe-in-the-Park coffee house.

Century Park Sheraton Hotel was renamed as ANA Hotel in 1990, and lasted until 2004. Capitaland, after its acquisition of the hotel, demolished and replaced it with Nassim Park Residences.

Cairnhill Hotel, Cairnhill Close (1979-1999)

Famous for its Coffee Garden and buffets in the eighties, the Cairnhill Hotel, at Cairnhill Close, began in the late sixties as Regency Hotel which was converted from a block of luxury flats. However, the construction of the hotel was incomplete due to financial issues, and remained so for the next decade.

It was not until 1979 when Tan Kim Hai, a Malaysian property developer, acquired the property and injected funds for the hotel to be fully built. Named Cairnhill Hotel, the newly-completed hotel was 11 storey tall and had more than 180 rooms.

Cairnhill Hotel was taken over by Wing Tai Holdings in 1996. It survived for another three years before the hotel was closed for good. The building was then torn down and replaced by a condominium named The Light at Cairnhill.

Singapura Forum Hotel, Orchard Road (1962-1985)

The $5.5 million Singapura Forum Hotel was one of the first hotels to be established at Orchard Road, and also the first hotel in Singapore to be managed by an international hotel chain – the Intercontinental Hotels group. The hotel, located at Orchard Road towards the Tanglin area, was opened in 1963, just one day after the formation of the Federation of Malaysia.

Forums and workshops by private organisations were regularly held at the eight-storey 200-room hotel, but the hotel’s profits in the early seventies were affected due to the intense competition with other new luxury hotels in the vicinity.

In 1972, Ng Teng Fong, a well-known property magnate, bought over the hotel. Initially wanted to demolish and replace it with shopping complexes, he instead sold it to a Dubai-based investment company in 1982 for $178 million.

Singapura Forum Hotel was eventually shut down in July 1983. It was replaced by Forum Galleria shopping and office complex that was opened in 1986. Even though they had long gone, the hotel’s popular Sentosa Restaurant and Pebbles Bar were still well-remembered by its former guests.

New 7th Storey Hotel, Rochor Road (1953-2008)

Despite its name, the New 7th Storey Hotel was actually nine storey tall. When it was completed in 1953, it was briefly the tallest building at the Rochor vicinity, and many taxi drivers and motorists used it as a landmark for their directions.

Despite its name, the New 7th Storey Hotel was actually nine storey tall. When it was completed in 1953, it was briefly the tallest building at the Rochor vicinity, and many taxi drivers and motorists used it as a landmark for their directions.

The New 7th Storey Hotel, founded by Wee Thiam Siew, began as a high end hotel, frequently patronised by European guests for stays in Singapore as well as British officers for tea parties.

But the hotel’s status declined by the late nineties, when it gradually became a budget hotel for backpackers.

In 2008, the half-century old New 7th Storey Hotel was demolished to make way for the new Downtown Line’s Bugis MRT Station.

Reborn Hotels – A New Lease of Life

Instead of demolition and redevelopment, some of the older hotels were sold, renovated and rebranded as new hotels. These include:

Ming Court Hotel (1970-1991), Tanglin Road, present-day Orchard Parade Hotel

Hotel New Hong Kong (1971-1979), Victoria Street, present-day Hotel Grand Pacific

Merlin Hotel (1971-1981), Beach Road, present-day Plaza Parkroyal Hotel

Apollo Hotel (1971-2004), Havelock Road, present-day Furama Riverfront Singapore

Paramount Hotel (1983-2010), Marine Parade Road, present-day Village Hotel Katong

Crown Prince Hotel (1984-2005), Orchard Road, present-day Grand Park Orchard

Dai-Ichi Hotel (1985-1999), Anson Road, present-day M Hotel

Published: 11 January 2018

In 1968, First Toa Payoh Secondary School (FTPSS) became Toa Payoh’s first secondary school, located at Toa Payoh Lorong 1. Initially made up of students from the nearby Kim Keat Vocational School and Thomson Secondary School, FTPSS was officially opened in May 1969 by Eric Cheong Yuen Chee, Member of Parliament (MP) for Toa Payoh, as an English and Chinese fully-integrated school.

In 1968, First Toa Payoh Secondary School (FTPSS) became Toa Payoh’s first secondary school, located at Toa Payoh Lorong 1. Initially made up of students from the nearby Kim Keat Vocational School and Thomson Secondary School, FTPSS was officially opened in May 1969 by Eric Cheong Yuen Chee, Member of Parliament (MP) for Toa Payoh, as an English and Chinese fully-integrated school.