The Formula One Singapore Grand Prix has been in the headlines lately. There is a possibility that Singapore will end the race after 2017, after statistics show that its most recent ticket sales and attendance are declining. The three-day weekend race, held at the Marina Bay Street Circuit every September since 2008, is the world’s only full night race so far.

The Early Days of Racing

The Formula One Singapore Grand Prix is not Singapore’s first motorcar race. The first Singapore Grand Prix was held 55 years ago, in 1961, at the Thomson Road Circuit. It was then organised, by the Singapore Motor Club (SMC) and sponsored by the Ministry of Culture, in an event named “Visit Singapore – The Orient Year”. The sport event was part of a campaign in promoting and boosting Singapore’s tourism sector in the sixties.

The Singapore racers, however, had an even earlier start. In 1948, a group of local motor sports enthusiasts founded the Singapore Motor Club, and organised races at South Buona Vista, Lim Chu Kang and Farrer Road. Some early local racers, such as Lim Peng Han and Osman Abbas, also competed at the Johore Grand Prix, a 3.7km long circuit running through the Johor Bahru town, in the early fifties. The Johore Grand Prix, first held in 1940 and ended in 1969, was one of the oldest races in Malaya.

Then came 1957, when an one-day race was organised by the Forces Motoring Club at the Royal Air Force (RAF) Changi’s 3.2km-long circuit. The 5-lap motorcar and 10-lap motorcycle races attracted 106 participants and almost 100,000 spectators. In the motorcar racing event, the winner Chan Lye Choon and his Aston Martin DB3S sprinted well ahead of the other contestants.

The 1957 race attracted much interest and fanfare but it turned out to be an one-off event. The Forces Motoring Club and Singapore Motor Club wanted other suitable sites for regular racing competitions, and the Sembawang circuit at the Old Upper Thomson Road, belonged to the War Department during that time, was one of the favourite choices. But the authorities would approve the circuit to be used only for motorcycle races, as it was deemed too tight and dangerous for motorcar racing.

Hence, the initial plan of a Singapore Grand Prix in the early sixties was to use a road circuit looping via Thomson Road, Whitley Road, Dunearn Road and Adam Road. But this would affect thousands of residents living in the vicinity. The Sembawang Circuit remained as the best choice, but it would have to be expanded to include the New Upper Thomson Road. Certain stretches of the roads that were narrow and bumpy would also have to be resurfaced and improved by the authorities.

Singapore’s First Grand Prix

Finally, the first Singapore Grand Prix was held over a weekend in mid-September 1961, promising entertainment and excitement for the spectators, both local and foreign. The Grand Prix kicked off on Saturday – the first day was more of an amateur and leisure contest, with motorcycles, vintage cars and saloons taking part in various races.

The main attraction came on Sunday, when two competitive races – one for the motorcycles and the other for motorcars – were hosted. Among the participating racing cars were established brands like Volvo, Lotus, Lola, Saab and Cooper, driven by famous Singaporean and Malayan racers such as Rodney Seow, Chan Lye Choon, Peter Cowling, Saw Kim Thiat and Yong Nam Kee.

Via the Old Upper Thomson Road and Upper Thomson Road, the competing drivers had to race in the 4.8km-long Sembawang Circuit that had several challenging bends with interesting nicknames such as Circus Hairpin, The Snakes, Long Loop and the Devil’s Bend.

The famous but dangerous Devil’s Bend, located near the entrance to the Upper Peirce Reservoir, was the most challenging of all. Shaped like the letter V, the chicane tested the skills and reactions of the qualified 30 racers, who had to complete 60 laps and a distance of approximately 286.5km, and the capabilities of their vehicles.

The first Singapore Grand Prix was a major success. Tickets, priced at nine ringgits for grandstand seats and one ringgit for general stands, were snapped up fast. Almost 20,000 spectators turned up for the first day’s races. On the second day, a 100,000-strong crowd packed along the sides of the roads to watch the speeding cars and motorbikes. Due to Grand Prix’s enormous success, Singapore’s tourism sector in 1961 posted a record revenue and number of tourists.

The Singapore Grand Prix gained global prominence and recognition in the subsequent years. The motorcycle racing event was listed in the international racing calendar since 1963, followed by the motorcar race three years later (although it was not considered a world championship).

By the early seventies, the races were telecast, with live commentary, across Asia, Australia and New Zealand. Over the years, the competitions of Singapore Grand Prix had improved to higher standards with professional racers from Japan, Indonesia, Thailand, Britain, The United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand participating together with the Singaporeans and Malaysians.

The old Singapore Grand Prix lasted 13 years between 1961 and 1973. In between, it was renamed as Malaysian Grand Prix from 1962 to 1965, when Singapore joined the Federation of Malaysia as a state. After independence, the racing event was named once again as Singapore Grand Prix.

End of the Races

In 1973, Singapore officially ended the Singapore Grand Prix. After the 13th annual race, the Singapore Sports Council (SSC) informed the Singapore Motor Sports Club, the event’s organiser, of the sudden decision. Safety concern was the main reason given, since there were several high profile fatal accidents occurred in the races over the years. As many as seven racers had died between 1963 and 1973. Many fans, however, believed it was a move by the authorities to discourage illegal motor racing.

After the ban of the Singapore Grand Prix, most of the local racers went over to Malaysia to train and compete. In 1974, star rider Gerry Looi led a team of Singaporean motorcycle racers to compete in the Selangor Grand Prix at the Batu Tiga Circuit.

Meanwhile, there were calls from the public to revive the popular races. The Singapore Motor Sports Club actively looked for sponsorship to build a complete circuit at Mandai, but the plan was called off due to the potential high construction cost of $5 million. Other alternatives were proposed, such as making use of a driver training circuit at Sembawang or a runway at Changi Airbase, but they were all rejected by the authorities. The Singapore Grand Prix did not make a comeback in Singapore until 35 years later.

List of Winners of Singapore Grand Prix (Motorcars)

1961 (1st Singapore Grand Prix) – Ian Barnwell, Britain (Aston Martin DB3S)

1962 (1st Malaysian Grand Prix) – Yong Nam Kee, Singapore (Jaguar E-Type)

1963 (2nd Malaysian Grand Prix) – Albert Poon, Hong Kong (Lotus 23)

1964 (3rd Malaysian Grand Prix) – race cancelled after 5 laps due to downpours

1965 (4th Malaysian Grand Prix) – Albert Poon, Hong Kong (Lotus 23)

1966 (1st Singapore Grand Prix) – Lee Han Seng, Singapore (Lotus 22)

1967 (2nd Singapore Grand Prix) – Rodney Seow, Singapore (Merlyn F2)

1968 (3rd Singapore Grand Prix) – Garrie Cooper, Australia (Elfin-Ford)

1969 (4th Singapore Grand Prix) – Graeme Lawrence, New Zealand (McLaren-Cosworth F2)

1970 (5th Singapore Grand Prix) – Graeme Lawrence, New Zealand (Ferrari V5)

1971 (6th Singapore Grand Prix) – Graeme Lawrence, New Zealand (Brabham BT30)

1972 (7th Singapore Grand Prix) – Max Stewart, Australia (Mildren)

1973 (8th Singapore Grand Prix) – Vern Schuppan, Australia (March 722)

List of Winners of Singapore Grand Prix (Motorcycles)

1961 – (1st Singapore Grand Prix) Chris Proffit-White, Singapore (Honda 4)

1962 – (1st Malaysian Grand Prix) Teisuke Tanaka, Japan (Honda)

1963 – (2nd Malaysian Grand Prix) Chris Conn, Britain (Norton Manx)

1964 – (3rd Malaysian Grand Prix) Akiyasu Motohashi, Japan (Yamaha)

1965 – (4th Malaysian Grand Prix) Akiyasu Motohashi, Japan (Yamaha)

1966 – (1st Singapore Grand Prix) Mitsuo Ito, Japan (Suzuki)

1967 – (2nd Singapore Grand Prix) Akiyasu Motohashi, Japan (Yamaha)

1968 – (3rd Singapore Grand Prix) Akiyasu Motohashi, Japan (Yamaha)

1969 – (4th Singapore Grand Prix) Tham Bing Kwan, Malaysia (Norton)

1970 – (5th Singapore Grand Prix) Ou Teck Wing, Malaysia (Yamaha)

1971 – (6th Singapore Grand Prix) Geoff Perry, New Zealand (Suzuki)

1972 – (7th Singapore Grand Prix) Geoff Perry, New Zealand (Suzuki TR 500)

1973 – (8th Singapore Grand Prix) Bill Molloy, New Zealand (Kawasaki)

Today, the Old Upper Thomson Road is a quiet winding road, where people use it mainly for jogging and cycling. Half a century ago, this was the venue that hosted one of Singapore’s most popular annual events.

Published: 26 November 2016

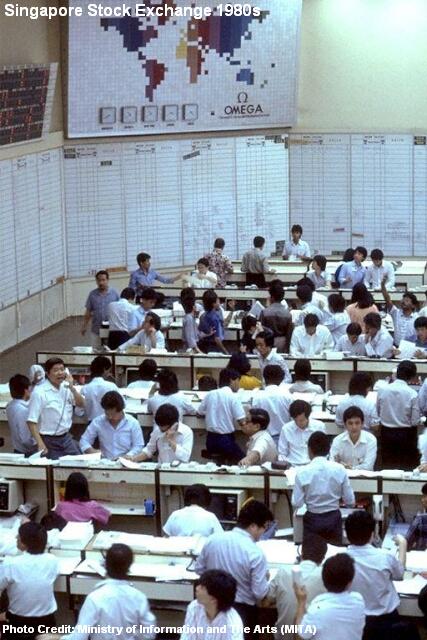

By end of November 1985, it almost spelt the death of the company as it went into receivership. Thousands of small shareholders had their investments and savings wiped out. Rumours of “white knights” rescuing the company gave hopes to the shareholders, but all optimisms were dashed in February 1986 when the liquidation proceedings of Pan-Electric commenced.

By end of November 1985, it almost spelt the death of the company as it went into receivership. Thousands of small shareholders had their investments and savings wiped out. Rumours of “white knights” rescuing the company gave hopes to the shareholders, but all optimisms were dashed in February 1986 when the liquidation proceedings of Pan-Electric commenced.

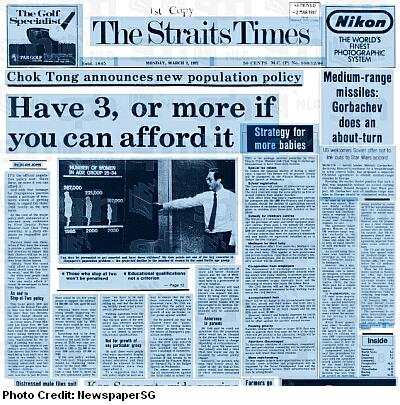

The Singapore government in 1986 switched from anti-natalist schemes to pro-natalist policies. Incentives such as childcare subsidies, tax rebates, allocation priorities in Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats were implemented.

The Singapore government in 1986 switched from anti-natalist schemes to pro-natalist policies. Incentives such as childcare subsidies, tax rebates, allocation priorities in Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats were implemented.

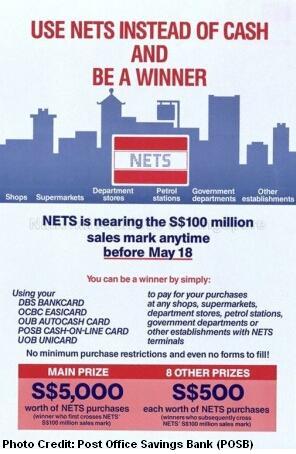

18 January – The Network for Electronic Transfers (NETS) was officially launched, as Singapore aimed to move towards a cashless society. The electronic payment service enabled more than 1 million users to make transactions through the NETS terminals at restaurants, shopping malls, petrol stations and government departments.

18 January – The Network for Electronic Transfers (NETS) was officially launched, as Singapore aimed to move towards a cashless society. The electronic payment service enabled more than 1 million users to make transactions through the NETS terminals at restaurants, shopping malls, petrol stations and government departments. After investigations, the police deduced the boys were unlikely to have run away from homes as they were both well looked after by their families. It was not kidnap either, since the families had never received any ransom demands. There were also no known cases of illegal trades then, and illegal traders would have taken more than two boys. In addition, the police did not think it was a murder or drowning case as the bodies of the two boys were not found.

After investigations, the police deduced the boys were unlikely to have run away from homes as they were both well looked after by their families. It was not kidnap either, since the families had never received any ransom demands. There were also no known cases of illegal trades then, and illegal traders would have taken more than two boys. In addition, the police did not think it was a murder or drowning case as the bodies of the two boys were not found.

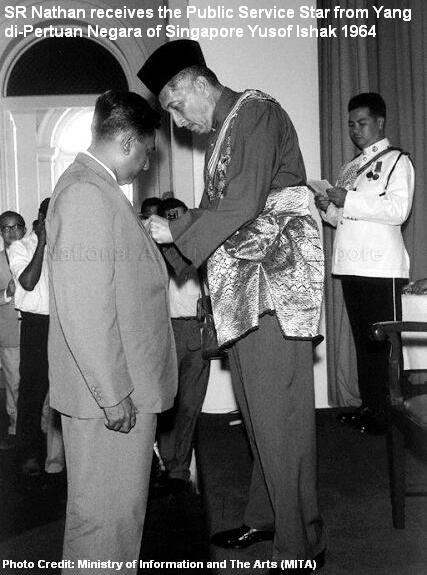

It was the early 1940s, and the impacts and horrors of the Second World War had reached Singapore. During the Japanese Occupation (1942-1945), Nathan, in a twist of fate, managed to master the Japanese language with the help of an English-Japanese dictionary. At age 18, he started working as an interpreter and translator to a high-ranking officer in the Japanese civilian police.

It was the early 1940s, and the impacts and horrors of the Second World War had reached Singapore. During the Japanese Occupation (1942-1945), Nathan, in a twist of fate, managed to master the Japanese language with the help of an English-Japanese dictionary. At age 18, he started working as an interpreter and translator to a high-ranking officer in the Japanese civilian police. After graduation, S.R. Nathan began his 40-plus-year career at the civil service, until the late nineties, taking on numerous roles at the Marine Department, Labour Research Unit, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Defence.

After graduation, S.R. Nathan began his 40-plus-year career at the civil service, until the late nineties, taking on numerous roles at the Marine Department, Labour Research Unit, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Defence.