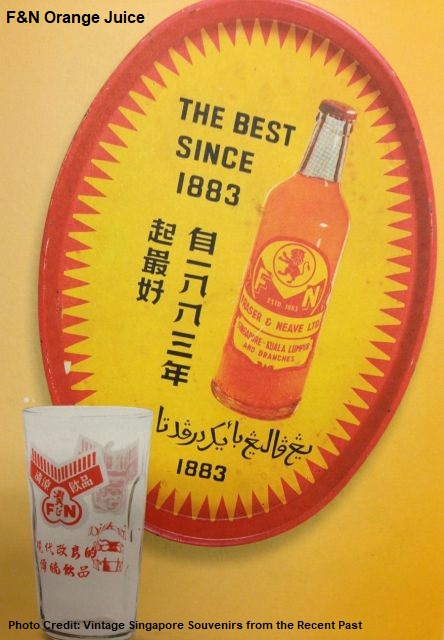

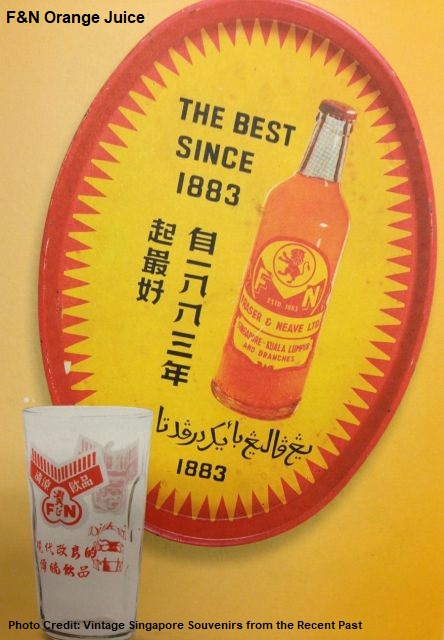

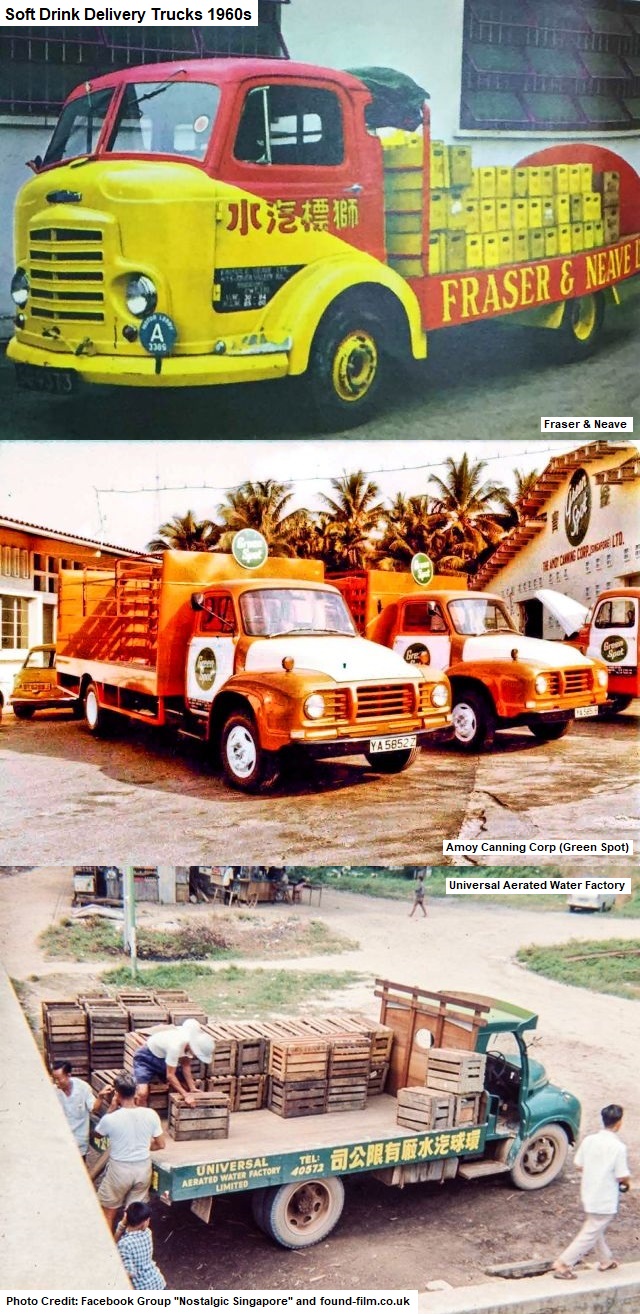

We used to call our favourite soft drinks bok zwee or hor lan zwee (“bottled water” or “Holland water” in Hokkien), or ang sai that refers to Fraser & Neave (F&N) orange juice (“red lion” in Hokkien; referring to the F&N logo displayed on their glass bottles).

For most of the ordinary folks, soft drinks in the past were not an everyday item, but a luxurious treat reserved only for the festivals, weddings, birthdays or other joyous occasions. It delighted the kids most, who would look forward to have their favourite fizzy or orangey taste of the soft drinks.

In general, soft drinks refer to non-alcoholic drinks, particularly those that are carbonated (or “aerated” before the mid-20th century). Coca Cola was introduced to the world in the 1890s, and still remains as one of the most popular soft drink brands today.

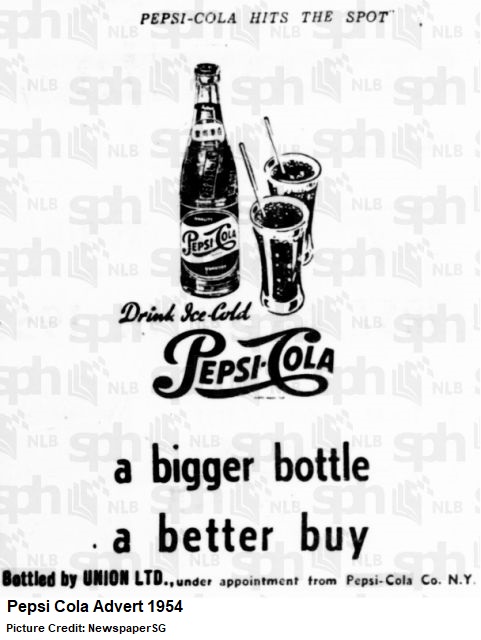

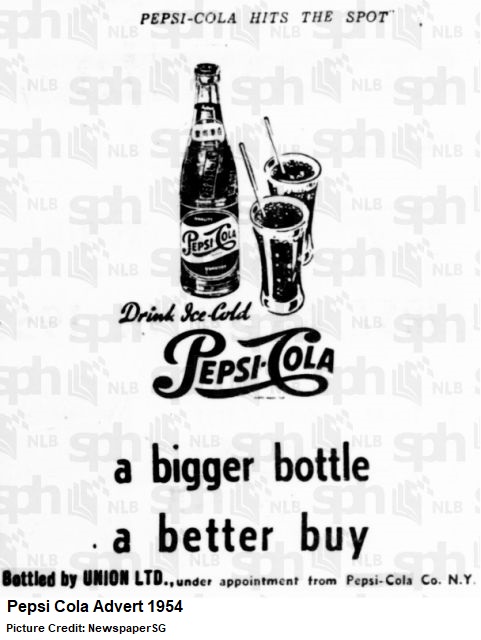

In Singapore, the range of soft drinks varied from the colas (Coca Cola landed in Singapore before the Second World War and Pepsi Cola in 1953) and fruit-based carbonated drinks (for example F&N Orange, Framroz, Sinalco, Green Spot) to the non-carbonated traditional drinks (such as Yeo Hiap Seng’s chrysanthemum tea, Dixon soyabean milk, herbal tea).

Some strong brands have flourished for decades, and remain successful till this day. Some were popular for only a few years, while a number had already vanished into history.

In 1980, the total manufacturing output of soft drinks in Singapore reached 130 million litres, almost doubled from the 77.6 million litres recorded a decade earlier in 1970. In the 1987 data collection by the Economic Development Board (EDB), Singaporeans gulped down an incredible 235.6 billion litres of soft drinks in that year, almost 2,000 times more than the 1980’s figure in the manufacturing output volume of soft drinks.

The popularity of these soft drinks, however, peaked between the eighties and 2000s, before many Singaporeans became health conscious enough to voluntarily cut down on the intake of these sweetened drinks.

Early Aerated Water Manufacturers

Prior to 1880, there were no manufacturers in Singapore producing soft drinks on a large scale. In 1883, John Fraser (1843-1907) and David Chalmers Neave (1845-1910) cofounded The Straits Aerated Water Company, which was converted into a limited liability company in 1889 known as Fraser & Neave (F&N). F&N’s long and successful legacy continues till this day.

In the early 20th century, the Seletar Springs was discovered and this led to the formation of The Singapore Hot Spring Limited that produced aerated waters for a number of years. The company, together with the springs, was then bought over by F&N to produce their star products in Vichy Water and Zom.

A couple of short-lived aerated water manufacturers, such as Harbour Aerated Water Factory (at Middle Road) and Oriental Aerated Water Factory, existed in the 1910s.

Three major aerated water manufacturers rose to challenge F&N during the pre-war period. They were Framroz, Popular Aerated Water Works and Phoenix Aerated Water Works.

Framroz was cofounded in 1904 by Phirozshaw Manekji Framroz (1877-1960) and Navroji Rustamji Mistri (1885-1953). Both of them were Parsi who came to Singapore from Bombay in the early 20th century. The Framroz brand lasted until the seventies (more information about Framroz below).

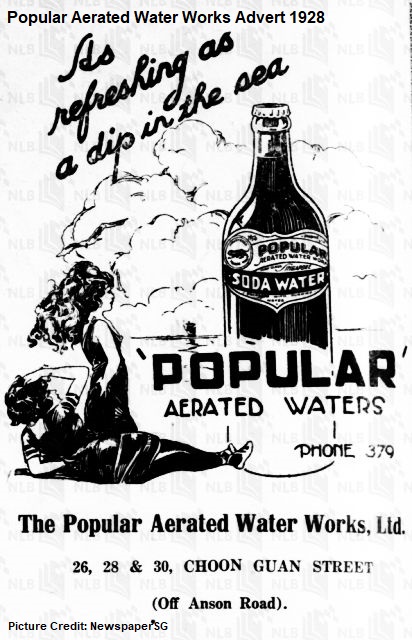

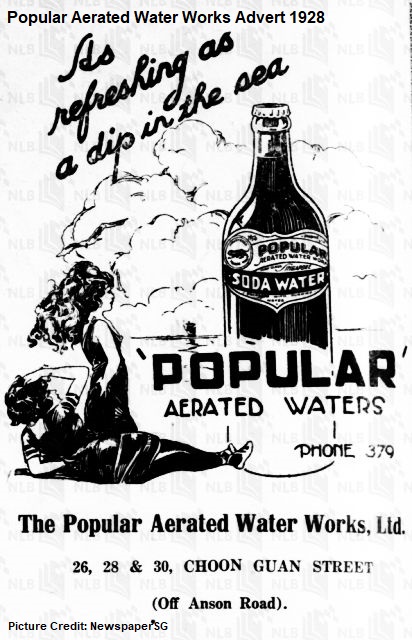

In 1924, a Chinese firm named The Imperial Aerated Water Company was established. It shifted to a larger premises at Tanjong Pagar’s Choon Guan Street in 1928 and was renamed The Popular Aerated Water Works Ltd. Under its new “Popular” name, its soda water was advertised with catching slogans such as “as refreshing as a dip in the sea“, “when the night’s devilish hot” and “knock the spots out of old sol (sun)“.

The company, however, went into liquidation and was acquired by prominent businessman and community leader Lee Choon Seng (1888-1966) in 1933.

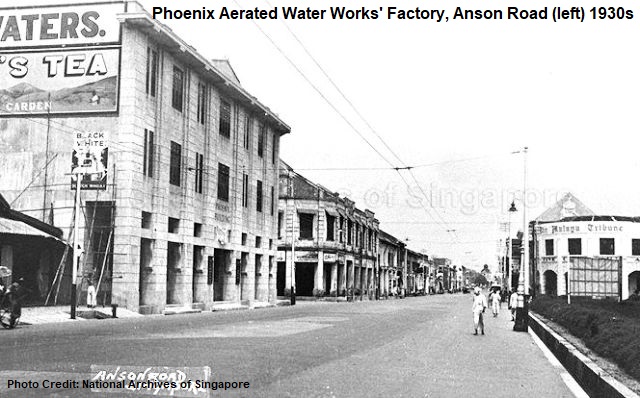

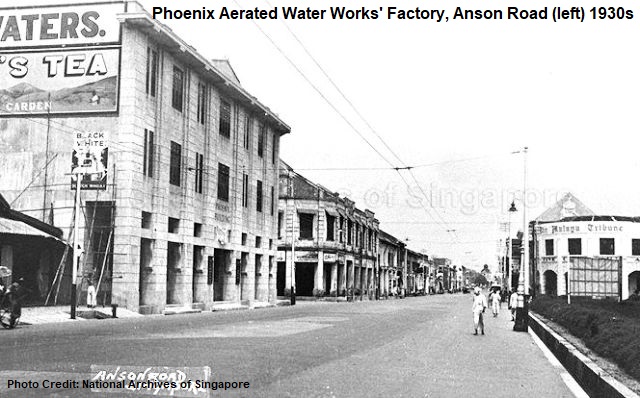

The Phoenix Aerated Water Works was started by Navroji Mistri in 1925 at Anson Road. This soured his relationship with Framroz and resulted into a years-long court case that ultimately ruled in Mistri’s favour.

In just a few years, Phoenix Aerated Water Works’ business expanded and began exporting its soda water, mineral spring waters, flavoured sweet drinks and fruit beverages to Malaya, Java, Sumatra, Borneo and India. The company lasted for almost half a century, before it was eventually wound up in 1972.

By the 1930s, there were as many as nine registered aerated water manufacturers in Singapore, with a large portion of the market shares dominated by F&N, Framroz, Popular and Phoenix. Together, the aerated water manufacturers in Singapore produced an estimated 25 million bottles of aerated waters a year in the 1930s.

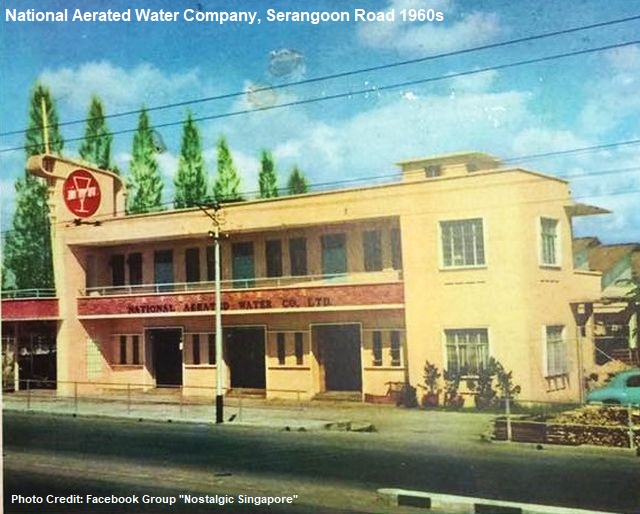

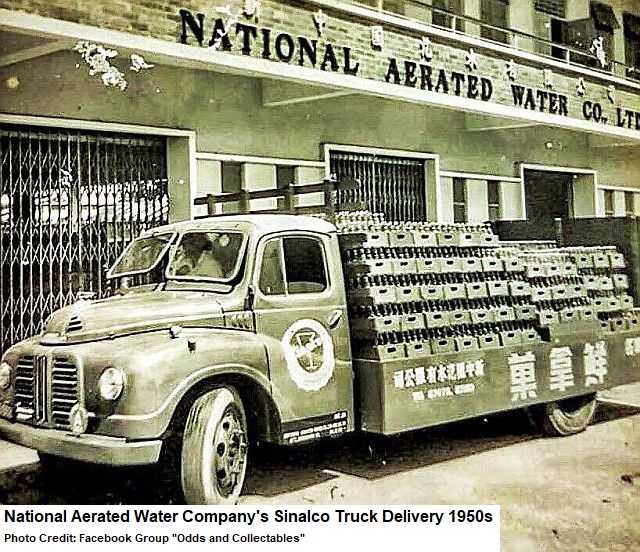

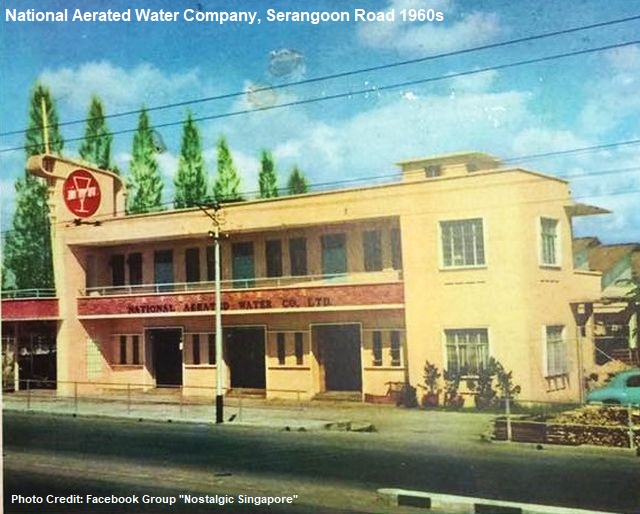

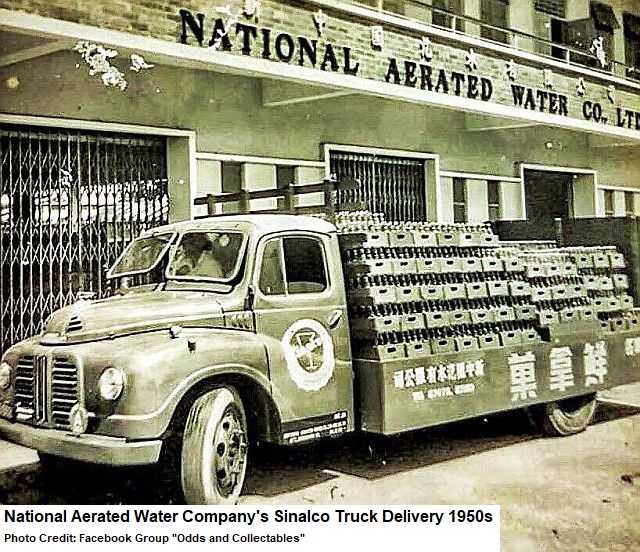

One smaller aerated water manufacturer that later grew to become the largest Chinese manufacturer of aerated water products in Singapore was the National Aerated Water Company. Started in 1929, it was able to produce popular orange juice, pineapple juice and sarsaparilla (root beer) after years of research.

By 1950, National Aerated Water Company’s daily production rose to more than 30,000 bottles, sold mostly to local consumers. Its Art Deco-style factory, built in 1954, was an iconic landmark along Serangoon Road for more than 60 years. The building was conserved in 2017 to become part of the new private condominium named Jui Residences.

Another major player in the local soft drink industry was the Eastern Aerated Water Company. The company had eight delivery trucks and more than 100 employees in 1950.

By 1951, Eastern Aerated Water Company’s Geylang Road factory was able to ramp up its production to 1 million bottles a month (or about 33,000 a day), similar to National Aerated Water Company’s daily production. It sold 16 kinds of soft drinks, including its house brands of Eastern Cola and Eastern Aerated Water, in both Singapore and Malaya in the fifties and sixties.

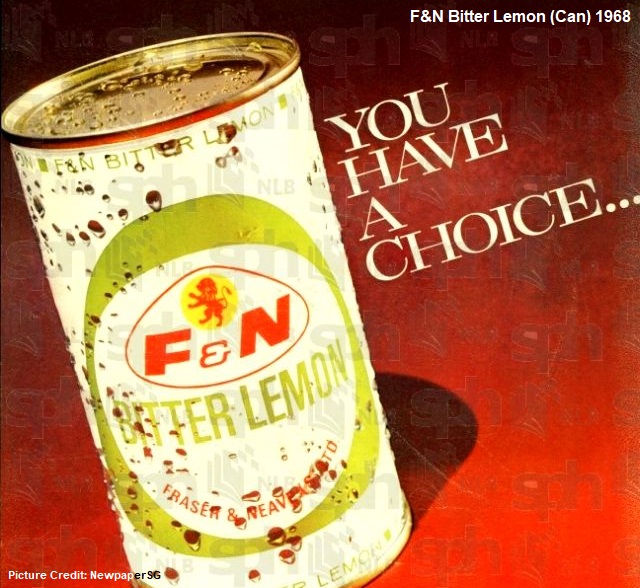

Singapore’s economy gradually recovered after the war, and this helped to lift the local soft drink industry. The bottling of soft drinks also evolved; while many of the drinks continued to be produced in glass bottles with metallic caps, aluminum cans were beginning to be widely used in the sixties.

Consumers were spoiled for choice when competitive soft drink brands, both local and foreign, flooded the Singapore market in the sixties and seventies. Among the popular ones were F&N, Coca Cola, Pepsi Cola, Framroz, Eastern Cola, Eastern Aerated Water, Long Bros, Suka, Sinalco, Kickapoo Joy Juice, Royal Crown Cola, 7-Up, Bubble Up, Mirinda and Green Spot.

Popular Soft Drink Brands

Framroz

Framroz was manufactured by Framroz Aerated Water Factory, first located at Cecil Street and later shifted to Telok Ayer Street. In the 1930s, the soft drink manufacturer claimed to be one of the first in Singapore to sell fruit juice in aerated form, including its popular Orange Smash, Pineapple Smash, Strawberry Smash and Raspberry Smash.

Framroz’s products were exported regionally to Malaya, Java, Sumatra and Borneo. Locally, its largest customers were the British military, institutes, and civil and military hospitals in Singapore.

In 1952, Framroz moved again, this time to Jalan Besar’s Allenby Road where it stayed until the end of its business in the seventies. Its Crown Orangia and Crown Pine Smash were heavily marketed as part of its carbonated and non-carbonated drinks made from imported fruits from California.

The company and brand peaked in the fifties and sixties, selling as many as 16 types of soft drinks with 11 flavours. Framroz’s fortune, however, declined in the late sixties and, despite an acquisition attempt in 1972 by another local food company Ben Foods, it was not able to survive past the seventies.

Sinalco

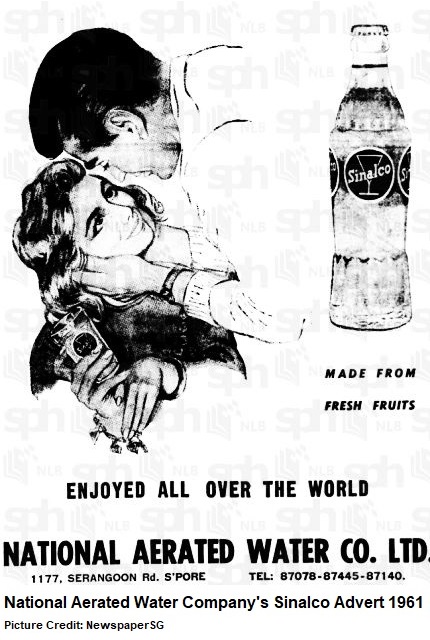

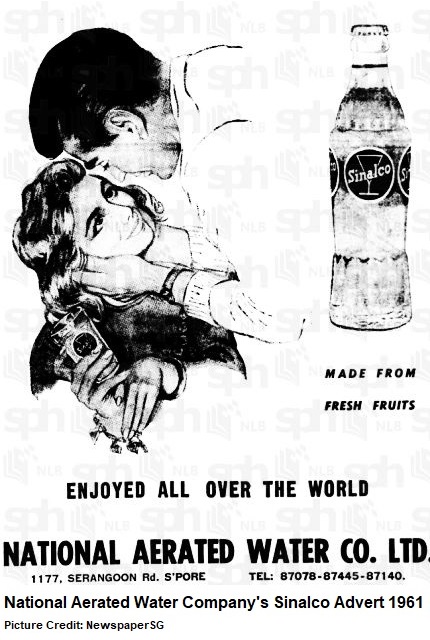

Famous German soft drink Sinalco was introduced in Singapore in the early 1950s and quickly gained popularity among Singaporeans with its unique taste that resembles a mixture of orange, lemon, blackberry, raspberry, strawberry and pineapple juices.

The name Sinalco is derived from the combination of the Latin words sine (“without”) and alcohole (“alcohol”), indicating that its drinks are non-alcoholic. Its Chinese name “鲜拿果” literally means fresh fruits.

Bottled by the National Aerated Water Company, the soft drink made its debut in 1953 at the Sinalco booth in the Great Eastern Trade Fair. The company’s $500,000 Serangoon Road factory was upgraded in 1954 with new machinery and technologies imported from Britain and the United States for more efficient bottling process.

National Aerated Water Company built another $350,000 factory at Kuala Lumpur in 1964 to bottle Sinalco. This production was solely to meet the Malaysia market’s increasing demands.

In 1965, a new variation of Sinalco, called Sinalco-Kola, was introduced globally. Another new version Sinalco Special was launched in the late seventies. Sinalco remains the oldest soft drink brand in Europe today, although its popularity in Singapore has considerably waned since the nineties.

Kickapoo Joy Juice

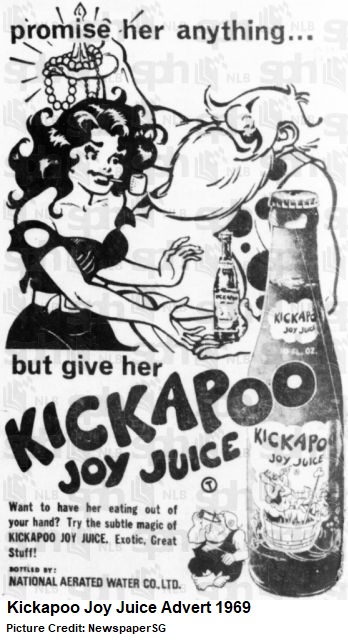

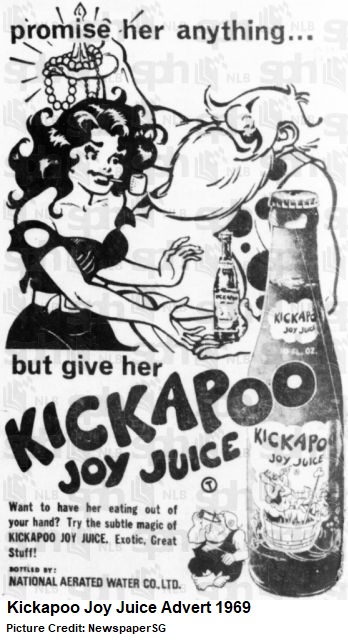

Kickapoo Joy Juice, a citrus-flavoured soft drink, was another popular product bottled by the National Aerated Water Company.

The name first appeared in Li’l Abner, an American comic strip that ran from 1934 to 1977. The Straits Times carried this comic strip in its papers during the sixties and seventies, raising public awareness of the name and drink (although it was depicted as an alcoholic drink in the comic). Some of the comic characters printed on the drink bottles became a recognisable part of the brand.

Kickapoo Joy Juice was introduced to the Southeast Asian markets after the mid-sixties. In Singapore, its refreshing taste was generally well-liked, making it a popular must-have drink during festivals or on a hot day.

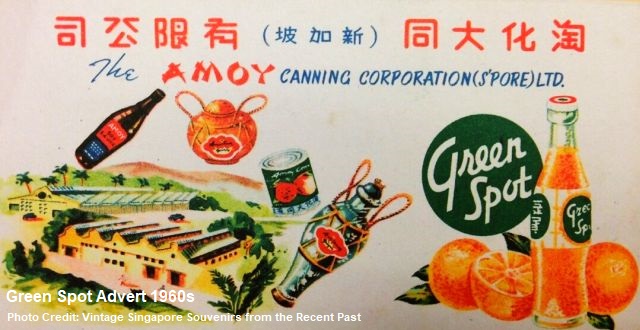

Green Spot

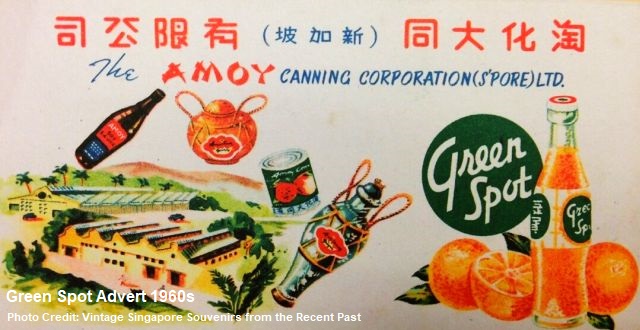

Green Spot was created as an American orange-flavoured soft drink in 1934. Making its debut in Singapore in 1939, it was sold at the luxurious hotels and cafes and advertised as a refreshing and invigorating drink made from “cane sugar and pure juice of fresh sun-ripened oranges“.

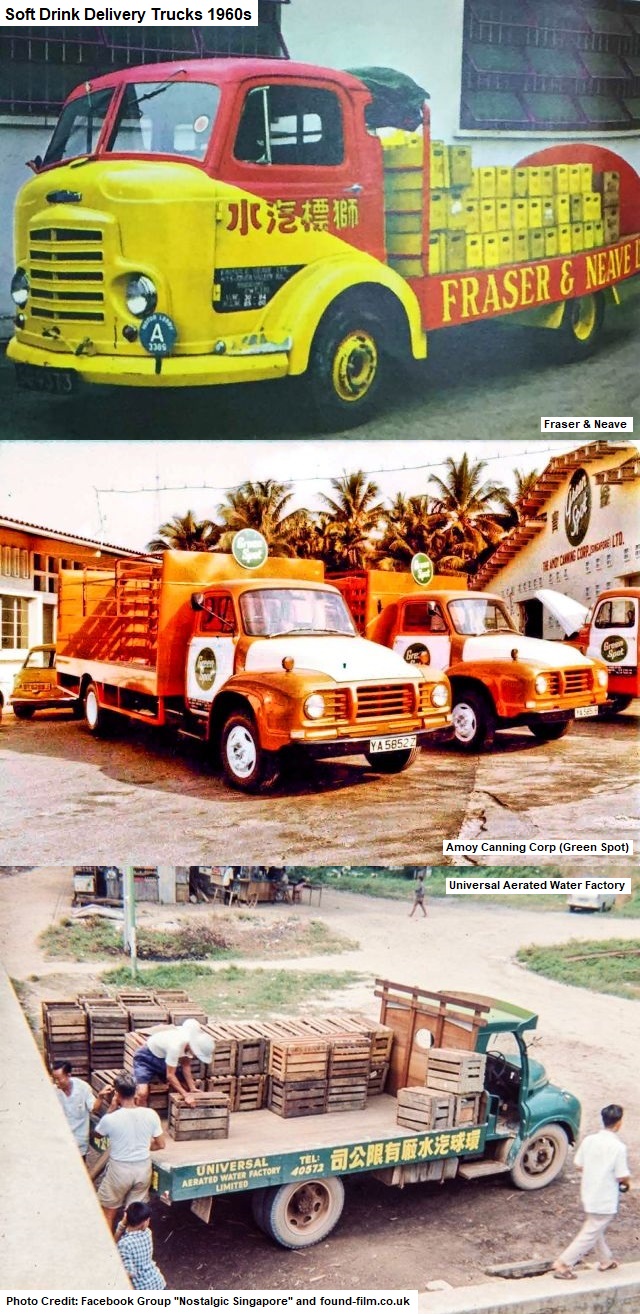

Green Spot became readily available to the common folks after the war, when Amoy Canning obtained the franchise rights to bottle the soft drink on a massive scale.

Founded in Amoy (Xiamen) of China in 1908, Amoy Canning started with soya sauce made from its home-made recipes. In 1949, the company expanded to Singapore with the building of a $1.5 million factory at Bukit Timah Road 8th milestone. Equipped with a modern bottling machine known as the premix gravity filler, Amoy Canning was able to produce 8,000 cases, or 192,000 bottles, of Green Spot everyday.

Besides Green Spot, Amoy Canning’s star products were Bubble Up, a lemon-lime-flavoured soft drink, and Dixon, a non-carbonated soya bean drink. Bubble Up was brought into Singapore from the United States in the sixties.

In 1994, Amoy Canning relocated its factory to Chin Bee Avenue in Jurong. It then shifted to its current premises at Bukit Batok in 2016. The century-old company is currently helmed by the fourth generation of the founder’s family.

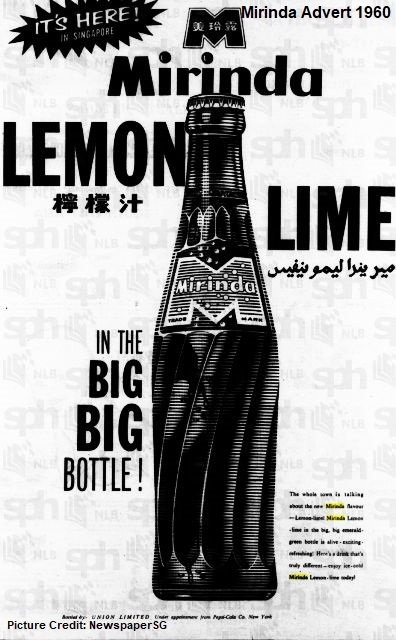

Mirinda

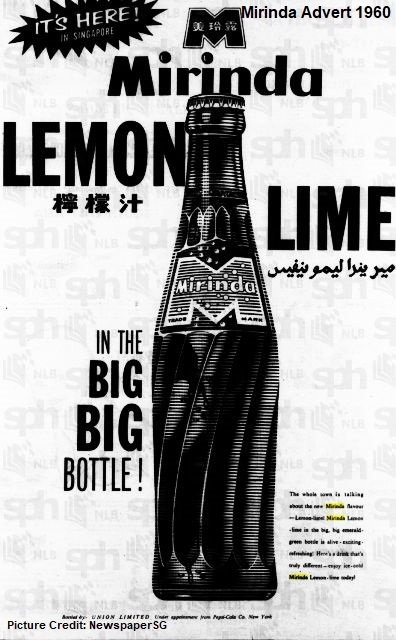

Mirinda, originated from the United States and introduced by Pepsi Cola International, made its debut in Singapore in 1957. Three years later, the company worked with local franchised bottler Union Pte Ltd, established at Havelock Road in 1950, to supply Pepsi Cola, Schweppes and Mirinda to the Singapore and Malaya markets.

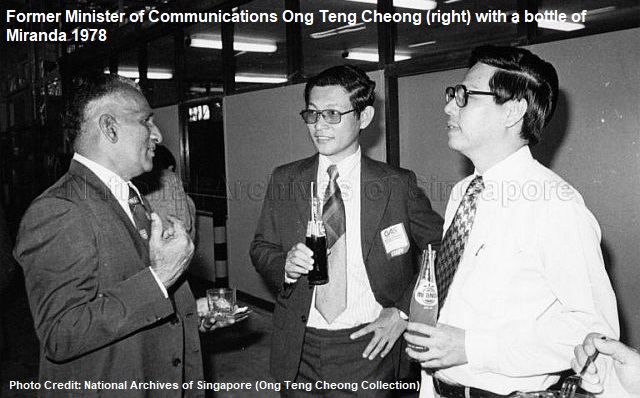

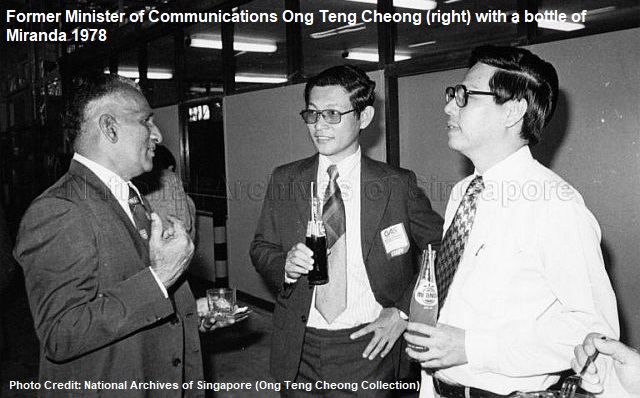

In 1969, Union moved to a new factory at Woodlands. Occupying a large area of 6,500 square metres, the factory was equipped with modern pre-mix machinery that were able to produce as many as 60 million bottles each year. Former Education Minister Ong Pang Boon (born 1929) officiated the opening of Union’s factory on 1 July 1969.

Mirinda Orange and Mirinda Lemon-Lime were sold in the sixties. In 1975, Pepsi Cola introduced a new flavour in Mirinda Strawberry. An aggressive one-month campaign was launched, with almost $180,000 worth of the new soft drink given away at several major public places such as supermarkets, swimming pools and the National Stadium.

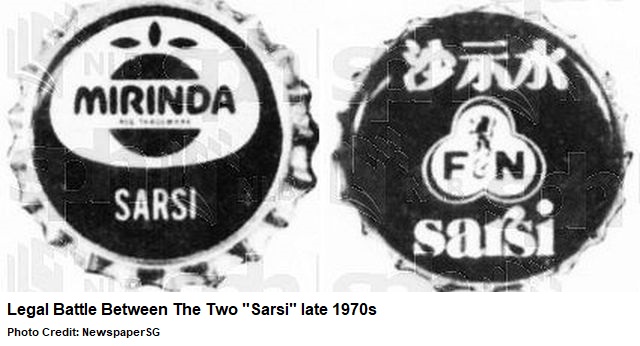

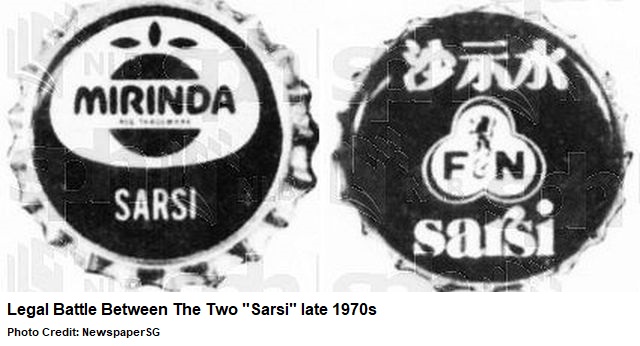

The local bottling of Pepsi Cola and Mirinda was taken over by Yeo Hiap Seng in the late seventies. A fourth taste – Mirinda Sarsi – was introduced to the local market in the late seventies.

This, however, led to a legal battle between Yeo Hiap Seng and F&N over the use of the name “sarsi“. The High Court eventually ruled in Yeo Hiap Seng’s favour in August 1980.

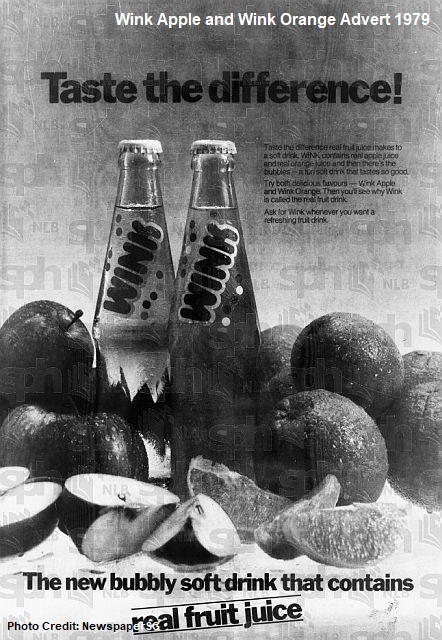

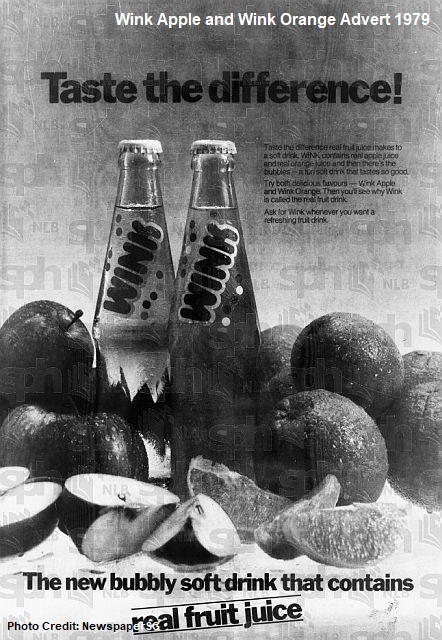

Other than Mirinda, Yeo Hiap Seng also brought in two more soft drinks for the local market in the late seventies. They were the Canada Dry, a Canadian soft drink well-known for its ginger ale, and Wink, an American soft drink that offered two flavours in apple and orange.

Fanta

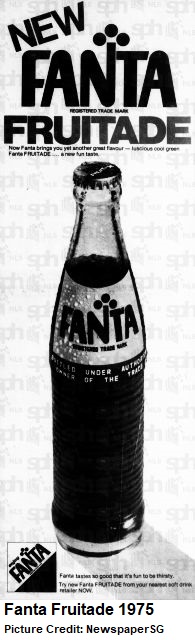

Carbonated fruity soft drink Fanta originated from Germany in 1941 during the Second World War. Due to the United States’ trade embargo of Nazi Germany, Fanta was created by Coca Cola’s German factory as an alternate option to the popular Coca Cola. After the war, Coca Cola took back the factory as well as Fanta’s trademarks.

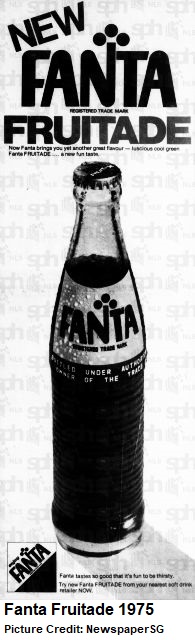

Fanta’s most popular flavour Fanta Orange was created in 1955. By the sixties, the soft drink had landed in Singapore and its bottling rights went to F&N, which already had been bottling for Coca Cola since 1936. Fanta introduced more flavours – grape, strawberry and fruitade – in the seventies.

In 1992, F&N and Coca Cola entered a joint venture to become F&N Coca Cola, with F&N holding 75% of the shares. To strengthen the new brand, F&N considered dropping Fanta Orange so that it could concentrate in selling only one orange drink – F&N Orange – to the local and regional markets. The plan did not materialise and Fanta Orange continued to be a popular soft drink in Singapore for the rest of the nineties.

Coca Cola vs Pepsi Cola

In the mid-eighties, the fierce rivalry between Coca Cola and Pepsi Cola, dubbed as the Cola War, spilled over from the United States to Singapore.

Coca Cola in the early eighties had introduced a new taste that became known as the new Coke. This move did not go too well with the consumers, and it forced Coca Cola to bring back the original taste under the name Coca Cola Classic. Pepsi Cola took the opportunity to mock their rival, claiming “it took us 87 years to beat the old Coke, but it only took us 87 days to beat the new Coke.“

In Singapore, things would turn out to be quite different. Coca Cola seemed to gain the upper hand when McDonald’s, established here since 1979, switched from Pepsi to Coke in 1985.

Other major fast food chains in Singapore that served Coke in the eighties were Kentucky Fried Chicken, Burger King, Wendy’s, Hardee’s, Orange Julius and A&W. In comparison, only Pizza Hut, Milano’s Pizza, Long John Silver’s and Big Rooster served Pepsi.

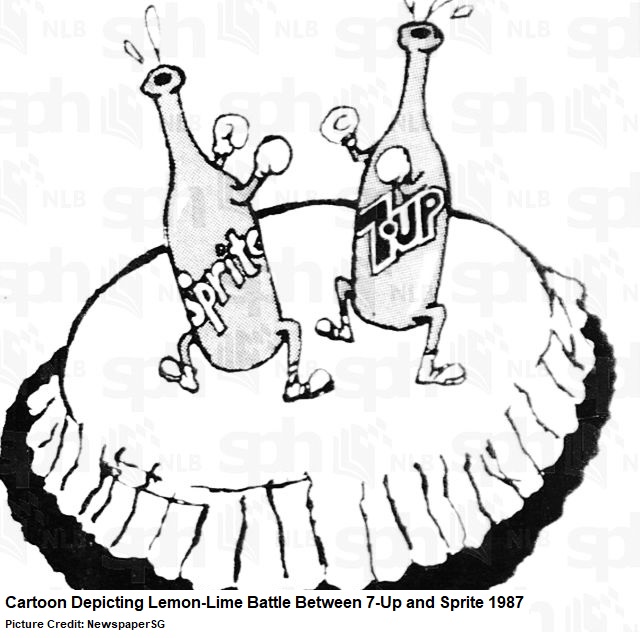

7-Up vs Sprite

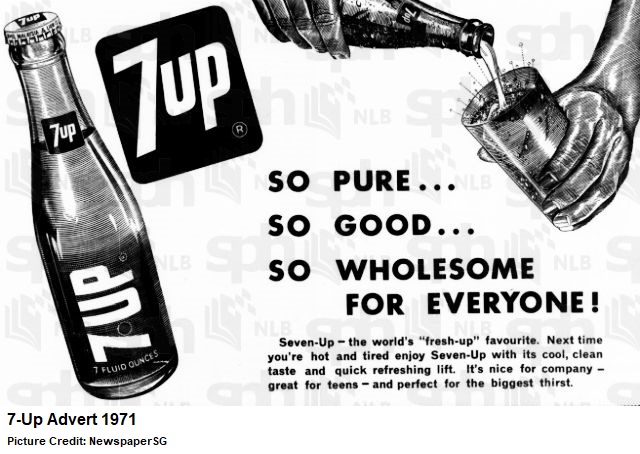

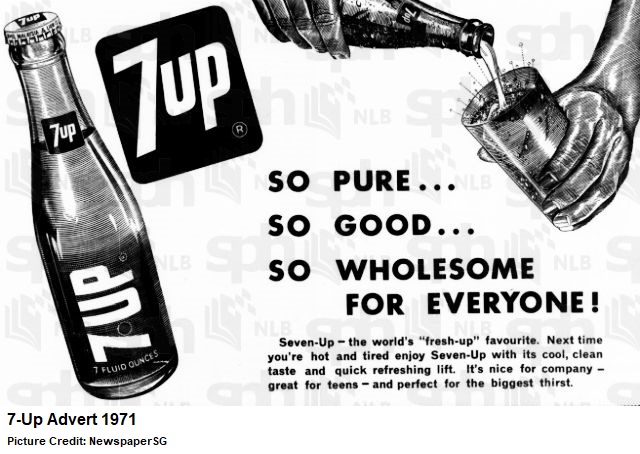

A major shakeup happened in 1986 when Yeo Hiap Seng was awarded the 7-Up franchise by Pepsi Cola. First introduced in Singapore in 1960 by Lion Ltd, a subsidiary of F&N, 7-Up grew to become Singapore’s leading lemon-lime soft drink brand in the eighties.

F&N then went on to take over the Sprite franchise previously under Cold Storage. Sprite was owned by the Coca Cola company. The late eighties witnessed the intense “lemon-lime battle”, as F&N’s Sprite competed with Yeo Hiap Seng’s 7-Up and Mirinda Lemon-Lime for the market shares. The “lemon-lime battle” was considered an extension to the Cola War between Coca Cola and Pepsi Cola.

In 1991, Pepsi Cola collaborated with Warner Bros and superstars to market its soft drinks. Pepsi Cola was endorsed by the likes of Michael Jackson, Madonna and Tina Turner, whereas Bugs Bunny and Looney Tunes characters were used to promote Mirinda, and 7-Up represented by popular cartoon character Fido Dido.

Change of Taste

Not all soft drinks enjoyed success in Singapore. In the eighties, Cold Storage, franchised bottler for Sprite, A&W Root Beer and Magnolia, introduced a mint drink that did not go down well among the Singaporeans. In 1982, an orange-flavoured barley drink was withdrawn from the market after only three months.

Meanwhile, more Singaporeans had become health conscious. There were concerns about the soft drinks’ sugar level, use of artificial sweeteners and the effect of caffeine on children.

In 1992, the major drink manufacturers in Singapore pledged to reduce the sugar content of their drinks in order to fight obesity in schools. The sugar level in their drinks would gradually be reduced from 10% to 8%. In the same year, the canteens of the schools, technical education and tertiary institutes in Singapore were instructed to stop selling Coca Cola, Pepsi Cola and other soft drinks with more than 10% sugar level.

The nineties and 2000s saw more beverage choices for the local consumers, such as isotonic drinks, ice blended coffee and bubble tea. On the other hand, soft drinks, despite the availability of sugar-free versions such as Diet Coke and Diet Pepsi, never quite shook off their unhealthy image and reputation. This led to a general consensus that soft drinks should not be consumed on a regular basis.

A list of popular soft drinks in Singapore throughout the years:

|

Soft Drink

|

Debut in Singapore

|

|

|

F&N

|

1883

|

F&N was established to produce carbonated soft drinks

|

|

Zombun

|

1909

|

Made by Singapore Hot Spring Ltd using Sembawang Hot Spring water

|

|

Zom

|

1920s

|

Introduced by F&N using Sembawang Hot Spring water

|

|

Vichy Water

|

1920s

|

Introduced by F&N using Sembawang Hot Spring water

|

|

Popular

|

late 1920s

|

Introduced by Popular Aerated Water Works

|

|

Lemonpop & Orangepop

|

1930

|

Lemon and orange juice-based soft drinks by Phoenix Aerated Water Works

|

|

Squeeze

|

1931

|

Orange juice-based soft drink by Popular Aerated Water Works

|

|

Marquisa

|

1932

|

Mixed fruit juice-based soft drink by Phoenix Aerated Water Works

|

|

Kasi Kola

|

1937

|

Bottled by Phoenix Aerated Water Works

|

|

Green Spot

|

1939

|

US orange-flavoured soft drink bottled by Amoy Canning Corp

|

|

Vimto

|

1930s

|

Advertised by F&N as a health fruit tonic that fought work weariness. Sold by Phoenix Aerated Water Works in the 1950s

|

|

Framroz

|

1930s

|

Known for its popular fruit juices in aerated form, such as Orange Smash, Pineapple Smash, Strawberry Smash and Raspberry Smash

|

|

Coca Cola

|

1930s

|

Popular US cola brand, bottled by F&N since 1936

|

|

Diet Coke

|

|

1985

|

Sugar-free Coca Cola, rebranded as Coke Light in the late 1990s

|

|

Cherry Coke

|

|

1986

|

Advertised with slogan of “Cherry Coke turns your world upside down”

|

|

Vanilla Coke

|

|

2003

|

Said to contain vanilla planifolia from South America

|

|

Coke Zero

|

|

2008

|

Sugar-free Coca Cola

|

|

Eastern Cola

|

1950

|

Introduced by Eastern Aerated Water Company

|

|

Pepsi Cola

|

1953

|

Popular US cola brand, advertised as “Tree of Life” beverage in the 1950s and bottled by Union Pte Ltd

|

|

Diet Pepsi

|

|

1985

|

Sugar-free Pepsi Cola

|

|

Pepsi Twist

|

|

2002

|

Lemon flavoured cola

|

|

Sinalco

|

1953

|

German soft drink bottled by National Aerated Water Company

|

|

Mirinda

|

Lemon-Lime

|

1957

|

US soft drink first bottled by Union Pte Ltd, then by Yeo Hiap Seng

|

|

Orange

|

1960s

|

|

Strawberry

|

1975

|

|

Sarsi

|

late 1970s

|

|

Kool-Aid

|

late 1950s

|

US soft drink in 4 flavours (orange, cherry, lemon, grape) and available in packet form for self making of soft drink

|

|

Suka

|

1960

|

US strawberry-flavoured non-carbonated soft drink bottled by Birely’s Ltd

|

|

7-Up

|

1960

|

US lemon-lime flavoured soft drink first bottled by Lion Ltd, then by Yeo Hiap Seng

|

|

Bubble Up

|

1960s

|

US lemon-lime flavoured soft drink bottled by Amoy Canning Corp

|

|

Kickapoo Joy Juice

|

1960s

|

Citrus-flavoured soft drink bottled by National Aerated Water Company

|

|

Fanta

|

Grape

|

1970

|

German soft drink bottled by F&N

|

|

Strawberry

|

1972

|

|

Fruitade

|

1975

|

|

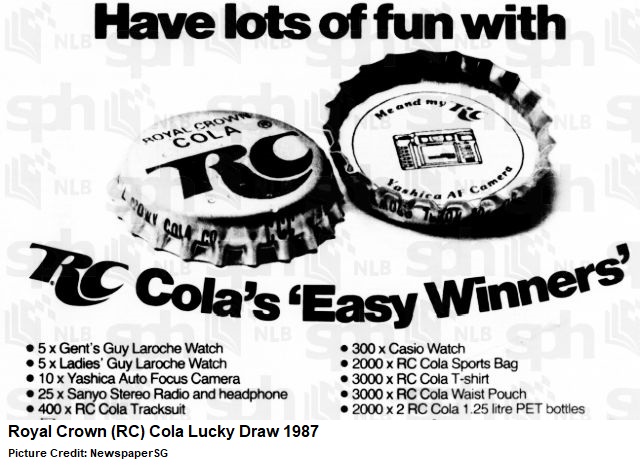

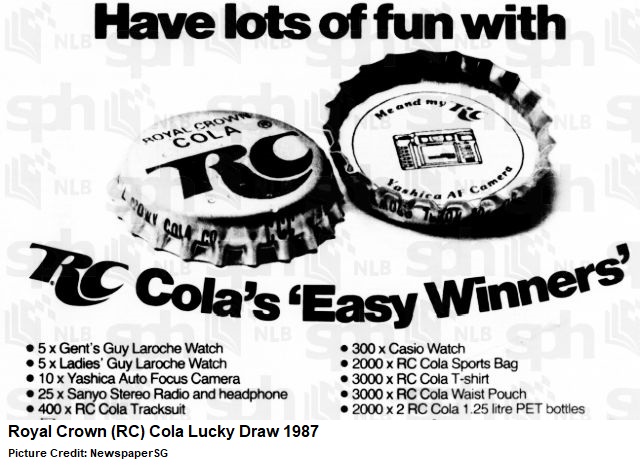

Royal Crown (RC) Cola

|

1972

|

Bottled by National Aerated Water Company

|

|

Wink

|

1979

|

US apple and orange flavoured soft drink distributed by Yeo Hiap Seng

|

|

Sprite

|

1980

|

First distributed by Cold Storage, then by F&N

|

|

100 Plus

|

1983

|

Launched by F&N as part of its 100-year commemoration

|

|

Ferrarelle

|

1992

|

Italian sparkling mineral water distributed by Yeo Hiap Seng

|

Published: 7 September 2024

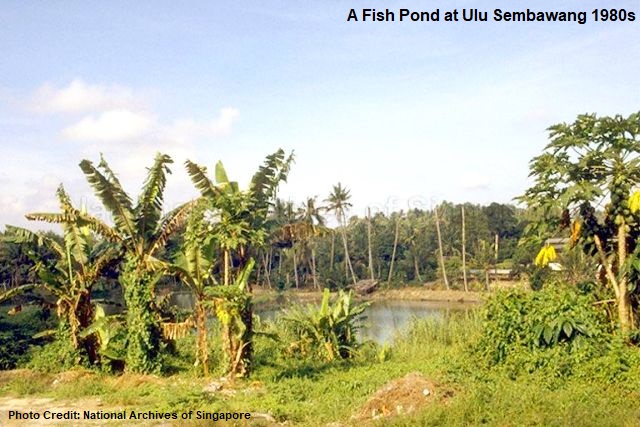

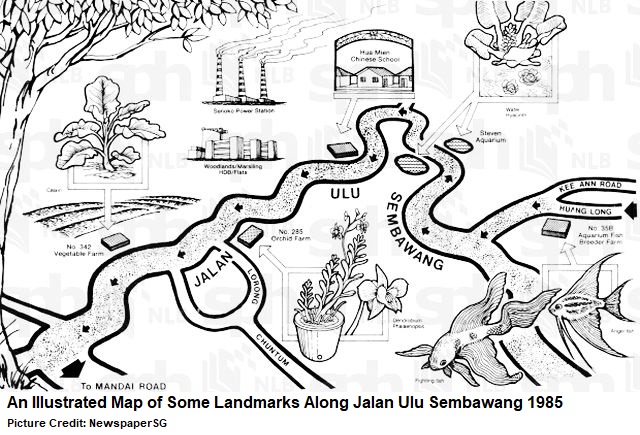

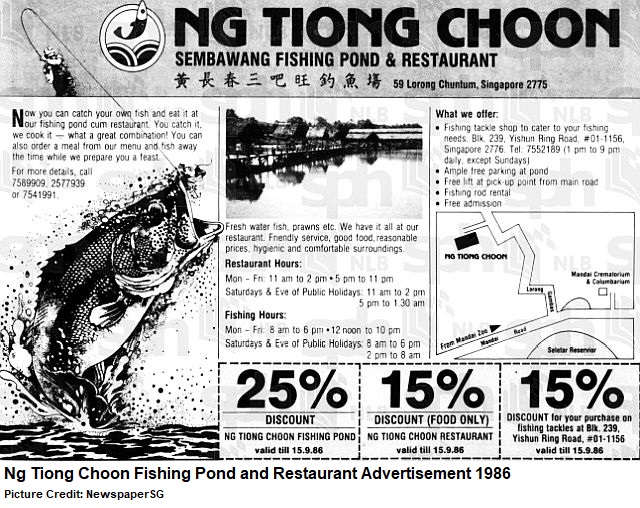

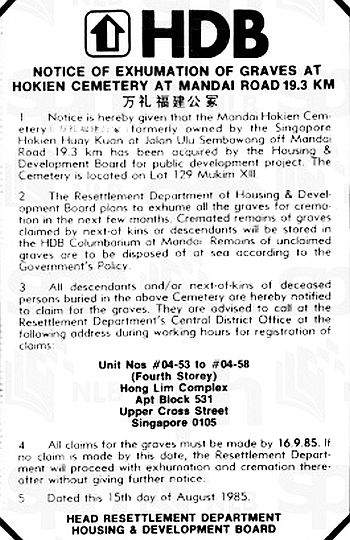

The Mandai Hokkien Cemetery at Jalan Ulu Sembawang was also

The Mandai Hokkien Cemetery at Jalan Ulu Sembawang was also

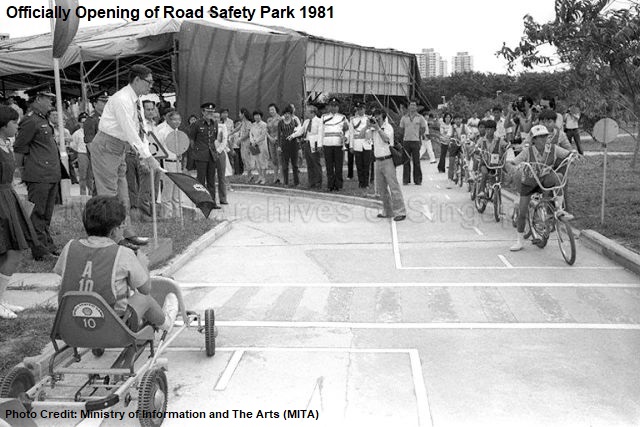

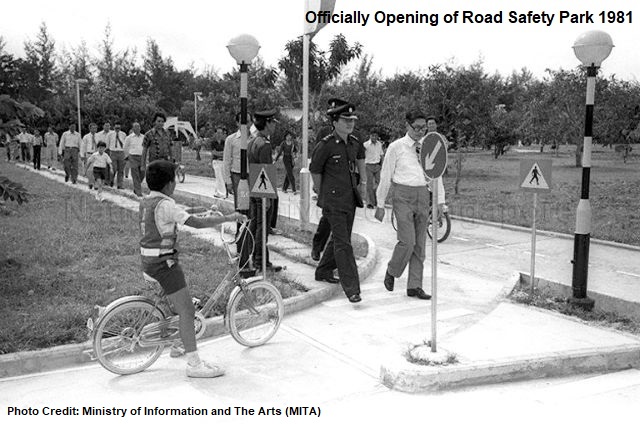

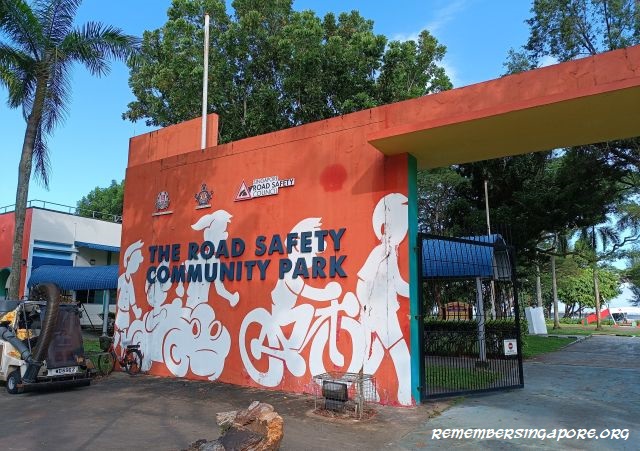

The Traffic Police unveiled a

The Traffic Police unveiled a

The Municipal Commission and Registry of Vehicles (ROV) did a trial run of motorised trishaws (nicknamed “trixis” or “trishaw-taxis”) in 1950. “Trixis” were commonly found elsewhere in Bangkok, Saigon, Hong Kong and Indonesia.

The Municipal Commission and Registry of Vehicles (ROV) did a trial run of motorised trishaws (nicknamed “trixis” or “trishaw-taxis”) in 1950. “Trixis” were commonly found elsewhere in Bangkok, Saigon, Hong Kong and Indonesia.