“Training to be soldiers

To fight for our land

Once in our life

Two years of our time

Have you ever wondered

Why must we serve?

Coz we love our land

And we want it to be free, to be free

Looking all around us

People everywhere

While they’re having fun

We are holding guns

Have you ever wondered

Why must we serve?

Coz we love our land

And we want it to be free, to be free

Stand up!

And be on your guard

Come on every soldier

Do your part

Do it for our nation

Do it for our Singapore”

After almost 18 years of active National Service (two-and-a-half years of full-time NS plus ten cycles of In-Camp Trainings), I finally received my precious MR (Mindef Reserve) certificate. Looking back, the unforgettable experiences were both fun and siong (tough). There were good and bad memories, as well as absolute nightmares in the confinements, devilish trainings and tekan by sadistic instructors. Memories of NS may be nostalgic to some, but most, if not all, will not want to go through it again.

NS life is a favourite chit chatting topic among male Singaporeans. Many like to reminisce their NS days, and compare whose units were the most siong. There are always countless tales to tell; from outfields and trainings to supernatural stuff.

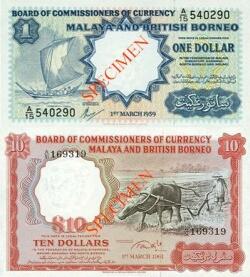

Pre-Independence Period

The British colonial government first mooted the idea of national service in 1952. The bill, named the National Service Ordnance, was passed by the Legislative Council and was supposed to come into effect in 1954. The new law required the local men of ages between 18 and 20 to be called up for trainings at the Singapore Military Force (SMF) or the Civil Defence Corps (CDC). Those who failed to register would be fined or jailed.

However, most locals rejected the new law. Thousands of local Indians left Singapore, while the Chinese middle school students organised aggressive protests. In May 1954, the National Service Riots broke out. As many as 2,500 students locked themselves at Chung Cheng High School. Police marched in to quash the riots, but the colonial government eventually backed down and “postponed” the bill.

Even though the students successfully forced the authority to reverse their decision, dozens of them were injured and arrested in the riots. The Chinese middle schools, in the later years, even became a breeding ground for pro-communist elements.

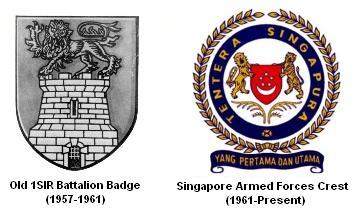

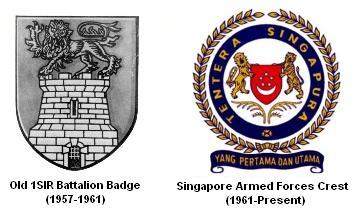

Singapore’s First Battalion

The history of local military regulars has gone a long way back. In April 1955, Singapore was given its first Legislative Assembly Election, with David Marshall (1908-1995) served as the First Chief Minister of Singapore. When Lim Yew Hock took over the partial self-government a year later, his hardline approach against the communists persuaded the British to grant Singapore more autonomy.

The history of local military regulars has gone a long way back. In April 1955, Singapore was given its first Legislative Assembly Election, with David Marshall (1908-1995) served as the First Chief Minister of Singapore. When Lim Yew Hock took over the partial self-government a year later, his hardline approach against the communists persuaded the British to grant Singapore more autonomy.

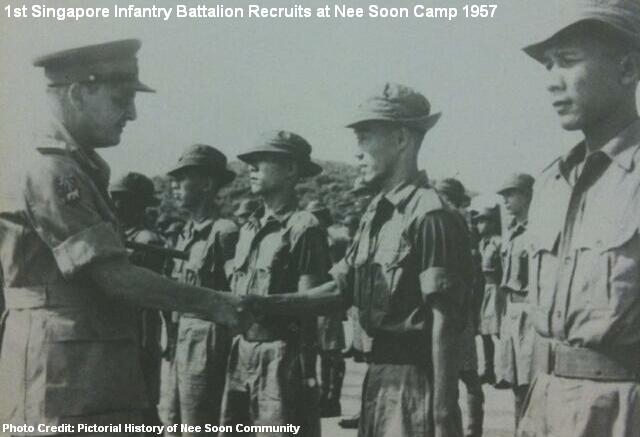

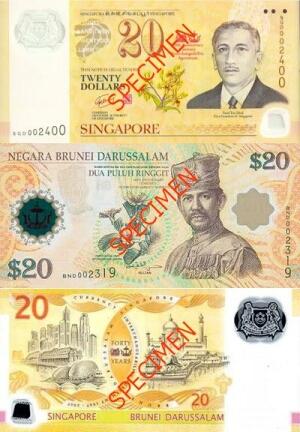

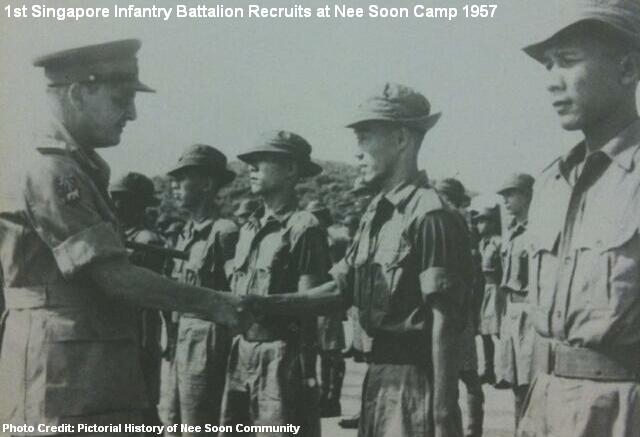

As the complete self-rule of the country became imminent, there was a need for Singapore to have its own military defence. On 12 March 1957, a total of 237 men born in Singapore was selected from an application pool of 1,420 to form the First Singapore Infantry Regiment (1SIR). Trainings of the new recruits were first carried out at Nee Soon Camp, which was still under the ownership of the British Army and was used to train their own forces.

The officers and men were later based at Ulu Pandan Camp, but it took six years before 1SIR reached its full battalion strength of over 800 men. The early roles of 1SIR was mainly to engage internal security and maintain civil order with the police.

The officers and men were later based at Ulu Pandan Camp, but it took six years before 1SIR reached its full battalion strength of over 800 men. The early roles of 1SIR was mainly to engage internal security and maintain civil order with the police.

During the merging with Malaysia and the Konfrontasi period against Indonesia (1963-1965), 1SIR was posted to Perak, Sabah and Johor for jungle trainings and defensive missions. The experienced battalion later produced many commanders to train the new enlistees when NS started in 1967.

Compulsory National Service

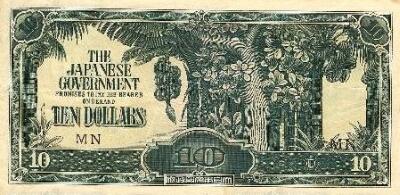

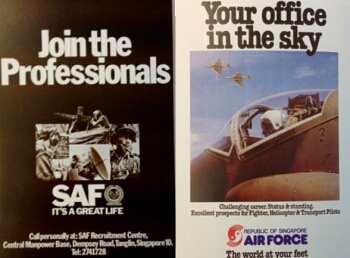

When Singapore attained independence in 1965, there was an urgency for the newly born nation to have its own defence force. Its two existing battalions of regulars were clearly insufficient, but any expansion of the army would cost a lot of money and put a strain on the economy.

Finance Minister Dr Goh Keng Swee (1918-2010) was appointed as the first Minister for Defence to work on the proposal in building up a sizable voluntary force to back up the regulars. However, when the British indicated their intention to reduce their forces in Malaysia and Singapore in 1966, the need for compulsory national conscription with reservist became the long term plan.

At the beginning, Singapore’s military development and directions were not determined. Several international case studies were conducted, and Switzerland was one of the considerations, based on the success of its economy and citizen army. In the end, Israel was deemed as a more suitable model. A secret pact with Israel was reached, with Israeli advisors flew in to train the first batch of graduates from the Singapore Armed Forces Training Institute in June 1967.

In the early days of Singapore’s independence, the military cooperation with Israel was never formally acknowledged, due to the sensitivity of a predominately Muslim region. The Israeli advisors, when arrived at Singapore, even had to take up the identities of “Mexicans” or “Indians”.

By January 1967, all new civil servants were required to undertake military training. A month later, the NS (Amendment) Act was passed in the parliament. On 28 March 1967, registration was first opened for all 18-year-old male Singaporeans. Only one tenth of the 9,000 applicants was selected for full-time NS due to the limited training facilities. The remaining was posted to part-time national service at the People’s Defence Force (PDF), the Special Constabulary and the Vigilante Corps.

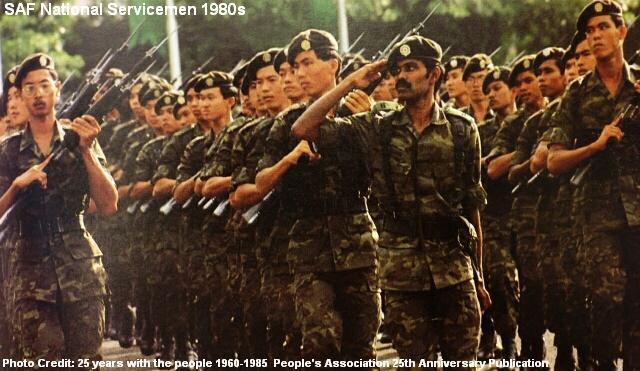

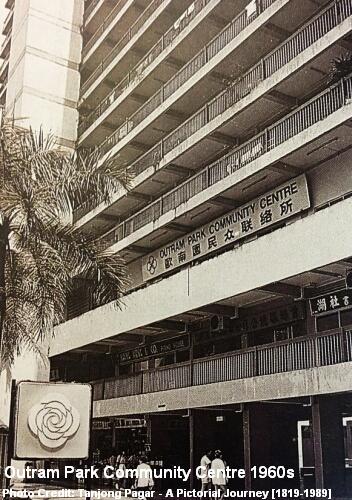

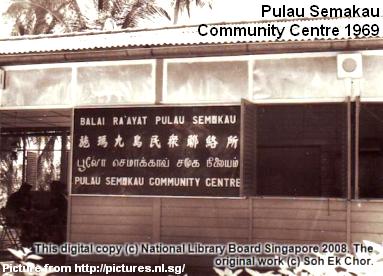

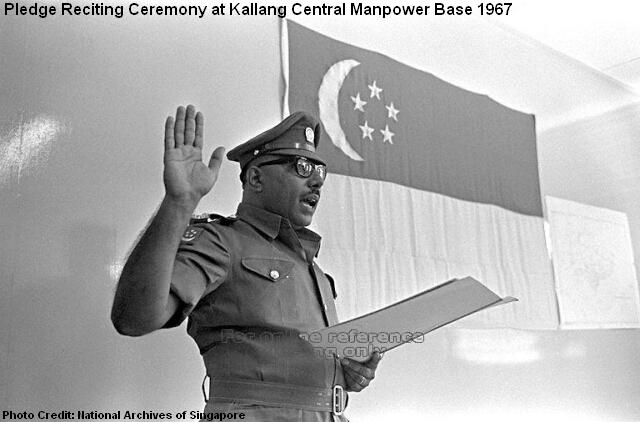

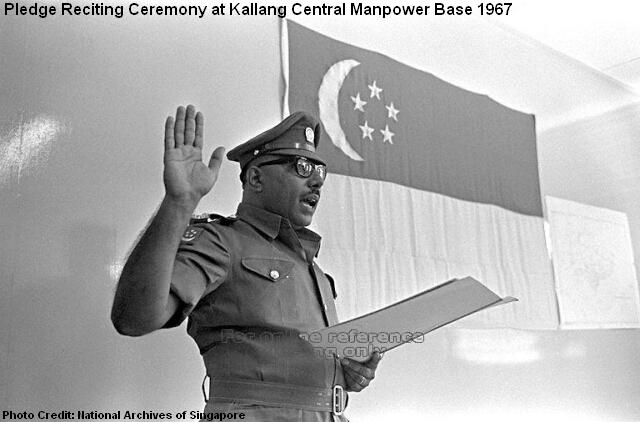

The 900 selected personnel were officially enlisted on 17 July 1967, added to the newly-formed infantry battalions of 3SIR and 4SIR after weeks of basic military training (BMT). Subsequent batches of fresh enlistees soon followed, reporting at the community centres or the Central Manpower Base.

In the late sixties and early seventies, send-off dinners and ceremonies were regularly organised at the community centres to boost the morale and the commitment of the new national servicemen, whose loved ones would line up along the roads to witness their departures on the three-tonner trucks.

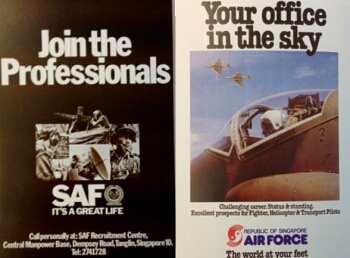

With the successful establishment of the additional infantry battalions and the new SAF Training Institute, other facilities such as the School of Artillery and School of Signals soon followed. In the late sixties, SAF also introduced its first scholarship program to attract the brightest talents to join the military as their careers. The university study fees and living expenses were offered in exchange for an eight-year bond with the armed forces.

With the successful establishment of the additional infantry battalions and the new SAF Training Institute, other facilities such as the School of Artillery and School of Signals soon followed. In the late sixties, SAF also introduced its first scholarship program to attract the brightest talents to join the military as their careers. The university study fees and living expenses were offered in exchange for an eight-year bond with the armed forces.

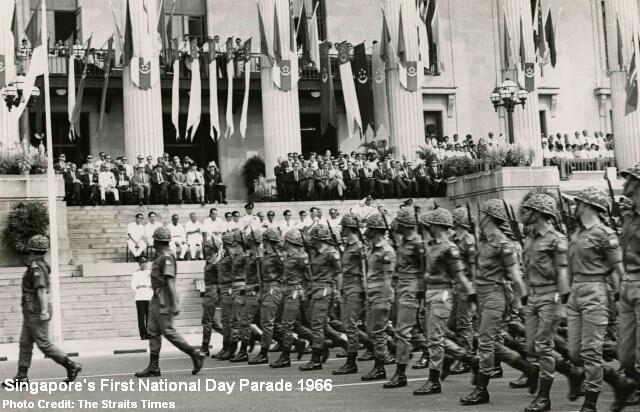

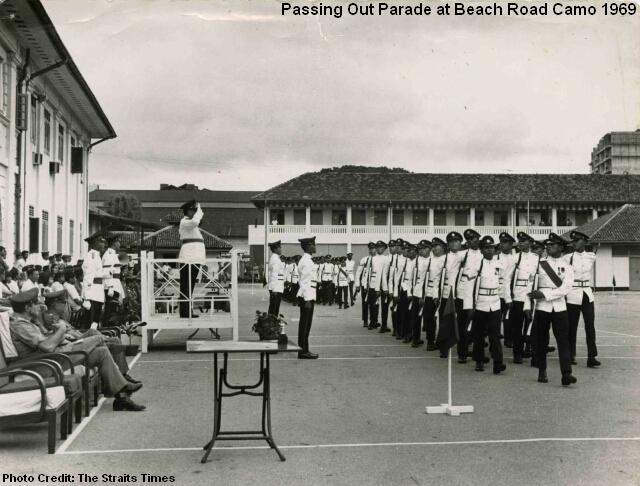

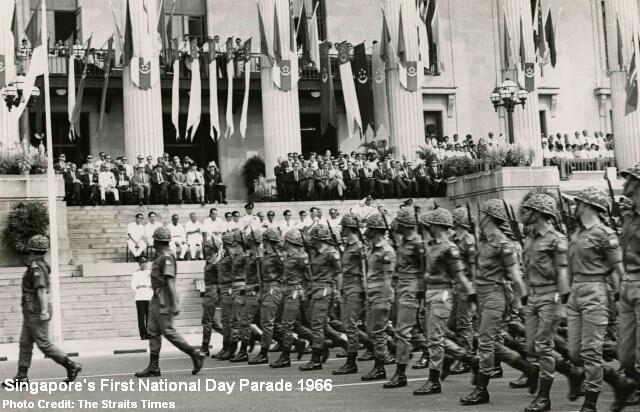

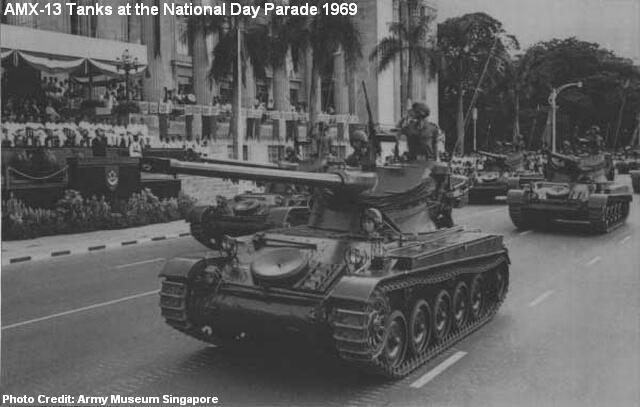

Singapore celebrated its first ever National Day on 9 August 1966. Six contingents, including the Singapore Infantry Regiment and the People’s Defence Force, marched past the building of City Hall, saluting then-President Yusof bin Ishak. Crowds of thousands cheered loudly as the troops continued their march to Chinatown and Tanjong Pagar. On 1st July 1969, Singapore also celebrated its first Armed Forces Day (SAF Day) to mark the armed forces’ loyalty and dedication to the nation. A 1,500-strong contingent of national servicemen and servicewomen was involved in the special day filled with parades and open houses.

The national servicemen of the sixties and seventies, beside trainings, took part in many gotong royong (helping out in the communities) such as tree planting, rivers’ clean-up, debris removal in flood-affected areas and road repairs at kampongs. Many were also activated for major rescue operations, notably the Laju Crisis in 1974, the Spyros Disaster in 1978, the Sentosa Cable Car Accident in 1983 and collapse of Hotel New World in 1986.

MINDEF and CMPB

Before its split into Ministry of Defence (MINDEF) and Ministry of Home Affairs in 1970, it was the Ministry of Interior and Defence (MID) which took charge of SAF. The ministry was established in 1965 with only a small office at Empress Place as its headquarters. It was then shifted to Pearl’s Hill Barracks in early 1966, sharing the premises with the Central Manpower Base (CMPB) and the Police Headquarters.

A year later, CMPB was moved to Kallang Camp. It was reunited with MINDEF at the Tanglin Barracks in 1972, after its buildings were left vacant by the departed British forces. This lasted 17 years until 1989, when MINDEF moved to its new headquarters at Bukit Gombak, while CMPB was relocated to Depot Road.

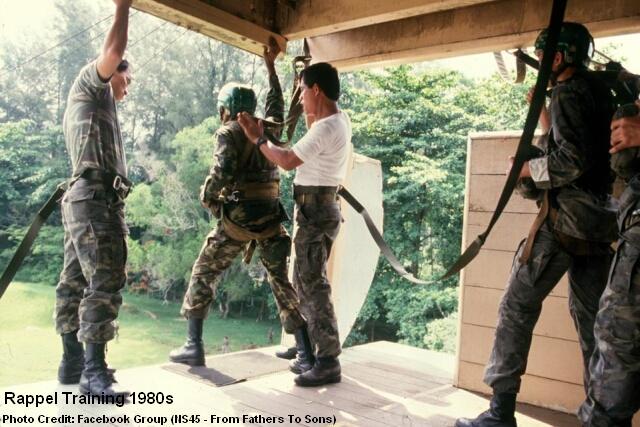

Training to be Soldiers

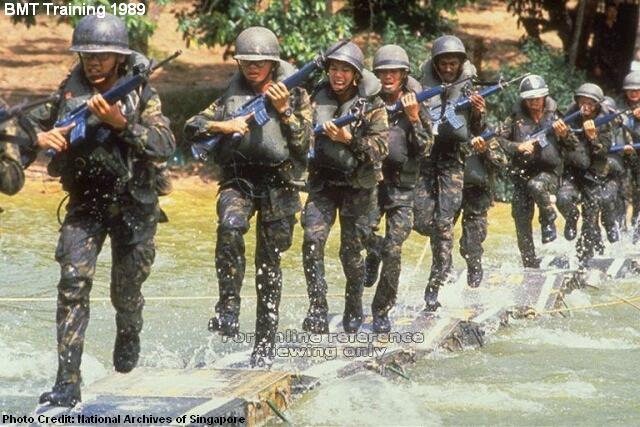

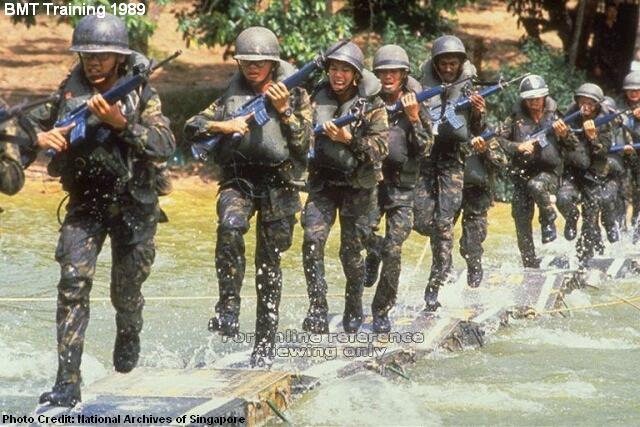

Before the official inauguration of the centralised Basic Military Training Centre (BMTC) in 1996, the recruits were trained in two major camps at Nee Soon and Pulau Tekong. A small number of other enlistees was recruited directly in units through the mono-intake system introduced since 1980.

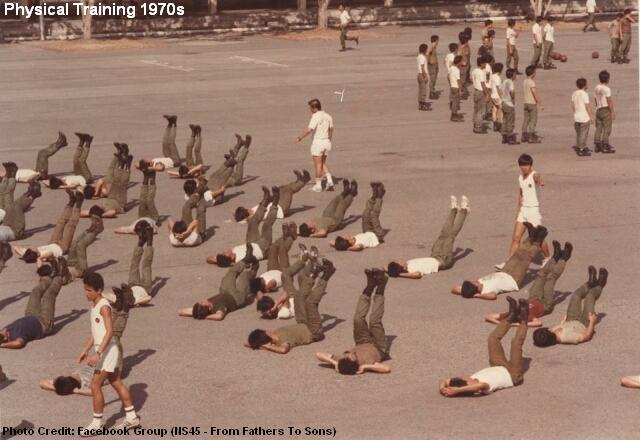

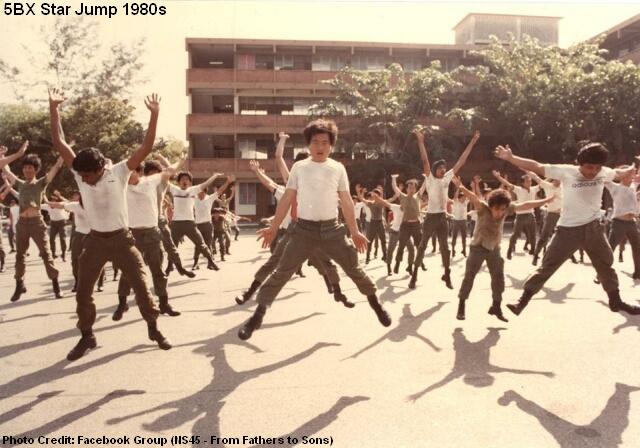

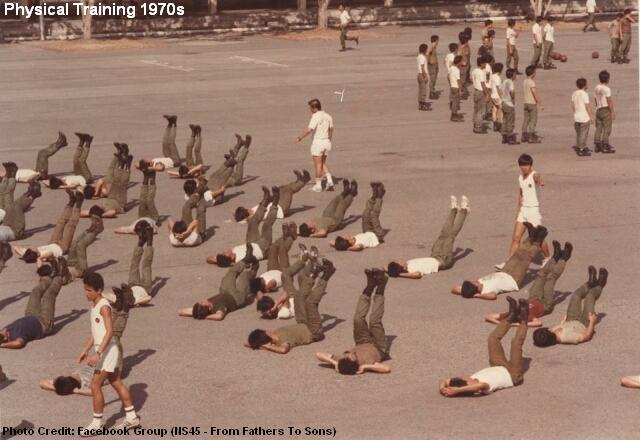

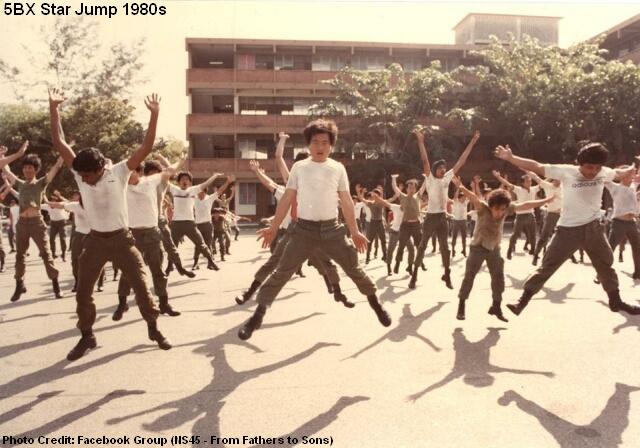

To many, the Physical Training Instructor (PTI) was a terror figure during BMT. Daily routine of morning exercises included jumping jack, burpees, star jumps, pushups, situps, half squats and others. Waking up at 5.30am, the recruits gathered at the parade square to do 5BX (5 Basic Exercises) in the darkness, followed by a short run before they could have their breakfasts.

To do more than 200 pushups in a morning session of physical training was a norm in the nineties. After the tekan, the body would ache so much that many could not lift their arms while changing shirts. Threading water for several minutes in the swimming pool was another gruelling exercise. Nevertheless, the tough physical trainings ensured the national serviceman was kept at his best fighting-fit condition.

Today, the likes of log PT and medicine ball are banned. Even the role of PTI is being outsourced to commercial fitness outfits.

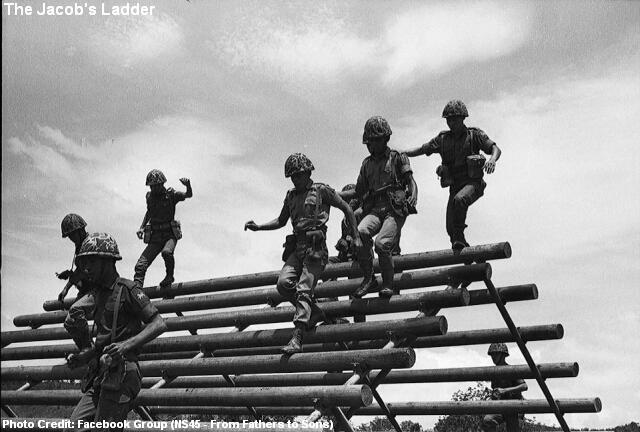

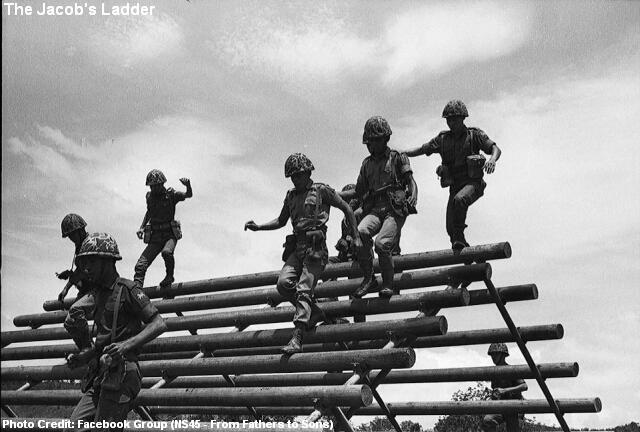

The Standard Obstacle Course, or SOC, was a nightmare for many.

Dressed in combat attire with SBO, helmet and rifle, this was one of the basic courses in BMT that a recruit must complete within 9 minutes.

A short 50m run was followed by a 1.83m low wall. Other obstacles were the monkey bars, stepping board, 3.5m rope, swinging bridge, balancing log, Jacob’s Ladder and a low ramp with concertina wires.

After clearing all the obstacles in this “military playground”, the recruit had to run another 600m before finishing the physically-demanding course.

The Battle Inoculation Course (BIC) was an interesting course a recruit had to go through in his BMT. It was a simulation of a battlefield environment during wartime, and the trainees had to get past barbed wires by doing leopard crawling and back crawling with live rounds flying above them. After an exhausting 90m of crawling and wiggling in the mud, the recruits would have to gather all their might to make a final charge at their “enemies”.

Many older Singaporeans would be familiar with the hand grenade training in BMT, influenced by the classic SBC drama The Army Series (新兵小传) in 1983, in which veteran actor Huang Wenyong played an acting role as a lieutenant who lost his life while saving a recruit during a hand grenade training.

In reality, the course was not as dangerous as it seemed. Trainees had to be familiarised through repeated throwing practices with a dummy grenade before they could actually try the real thing. Standing behind a concrete barrier, the recruit had to release the safety pin before throwing the live grenade and witnessing its explosion six seconds later.

The instructor must keep his calm at all time, but even the most experienced ones would be unnerved by three types of recruits, namely the blur sotongs, the gan cheong spiders and those with sweaty palms!

Chemical Agent Training used to be one of the courses in BMT. Trainees donned in masks and full body suits had to go through a tear gas-filled chamber. The worst experience was not the eye-burning sensation caused by the tear gas but the sight and smell of those stains of tears, saliva and mucus on the used mask!

The eight-week BMT was rounded off with a six-day field camp and a 24km route march in FBO (Full Battle Order). But it was not over yet! In fact, it was just the beginning of a two-year (two-and-a-half year previously) National Service. Different batches of national servicemen, depending on their vocations, went to experience different types of training courses.

Cheong sua, literally “means charging (up) the hill” in Hokkien, is a phrase used to describe basic infantry training. The tactical movement was by no means an easy feat. Many national servicemen could recall their exhausted days at the notorious Peng Kang Hill and Elephant Hill (at Pasir Laba) and Botak Hill (at Pulau Tekong).

In the 1970s, there were many small knolls at the training area between Woodlands and Mandai, such as Hill 180 and Hill 255, which were named according to their heights (in feet). The most famous was perhaps Hill 265 with its steep barren slopes covered with orange mud. Part of it was flattened in the nineties due to the construction of the Seletar Expressway (SLE).

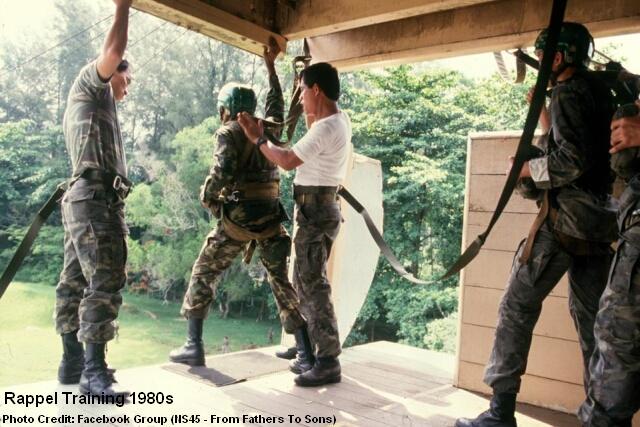

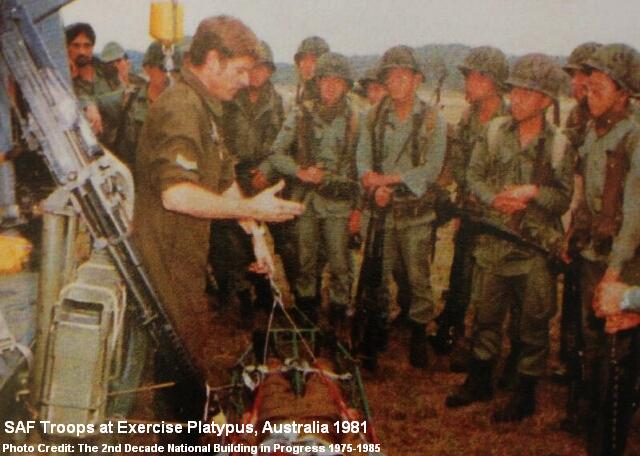

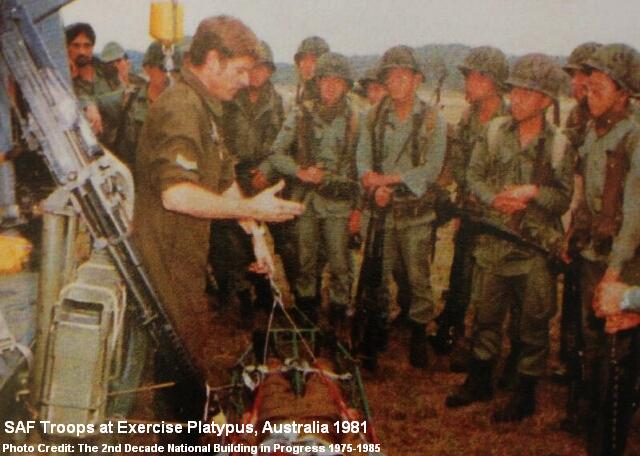

Not all national servicemen had the chance to experience it, but for those who did, the oversea exercises at Brunei were unforgettable experiences, or nightmares. Its thick and dense jungles made Singapore’s Mandai or Sungei Gedong look like playgrounds.

Wearing sweat-drenched No. 4 and carrying heavy weapons, the soldiers had to trek long distances over hilly areas filled with commando-trained mosquitoes, sand flies, armies of giant ants and, occasionally, some mean-looking centipedes. As if the physical toil was not enough, there were also rumours that the jungles contained many restless souls of previous National Servicemen who got lost in the thick vegetation and never made it back home.

Life in the Army Camps

Beside combat trainings and physical exercises, national servicemen had to learn to adapt to routine life in the army camps, sharing bunks with each other and working hand in hand to ensure the required disciplinary standards were met.

Unlike today, the past national servicemen had to do all the area cleanings themselves, taking turns to wash the toilets, empty the drains and clear the dry leaves on the carparks. Beds had to be made each morning with wrinkle-free bedsheets. The boots must be polished gilat gilat, and displayed neatly along with the shoes and slippers by the beds. The items in the cupboards should be placed in their orders, with the shelves kept dust-free.

Unlike today, the past national servicemen had to do all the area cleanings themselves, taking turns to wash the toilets, empty the drains and clear the dry leaves on the carparks. Beds had to be made each morning with wrinkle-free bedsheets. The boots must be polished gilat gilat, and displayed neatly along with the shoes and slippers by the beds. The items in the cupboards should be placed in their orders, with the shelves kept dust-free.

The two-week confinement period during BMT was perhaps the most restricted period for the national servicemen. In those days without internet or handphones, the connection with the outside world was basically cut off. At nights, the recruits queued up in long lines at the coin phones, while others tried to find pleasure listening to their walkman. Leisure time was short anyway, as the lights had to be off by 10pm.

Despite the authority’s denial, the existence of “white horse” was never in doubt. Those who had the “luck” to be part of a BMT platoon or company with a “white horse” would enjoy more canteen breaks and less punishments!

Life in the units was generally better, but new birds were likely to be tekan with constant stand-by-bed, turn-outs (in the middle of the night) and change parades in their first few weeks. The worst of all was the falling-in of beds’ and cupboards’ at the parade square. Imagine carrying those heavy and bulky cupboards up and down three or four levels. Luckily for the new national servicemen, this sadistic practice is banned today.

Rifles as Wives

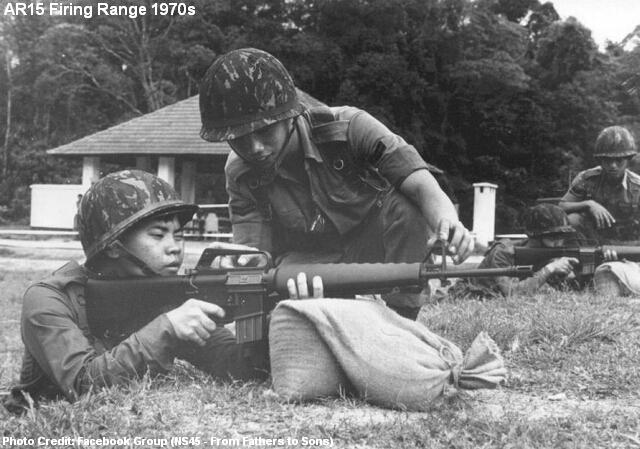

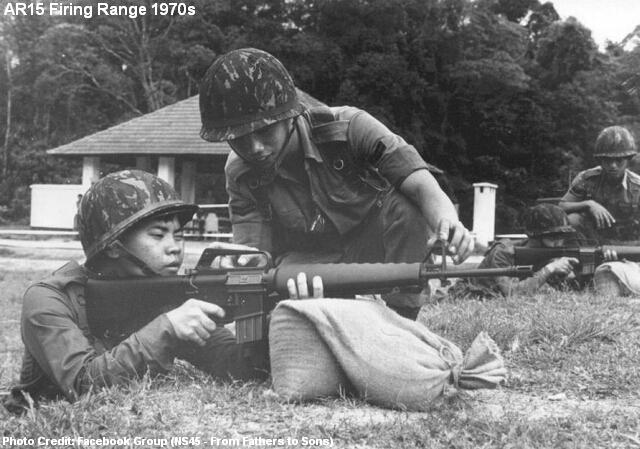

On the first day when M16 (or SAF21 today or AR15 before the 1980s) was handed to a recruit, he was taught that he must treat the 3.3kg weapon like his wife.

It was a grave mistake to lose one’s rifle. Without his weapon, a soldier was like a vulnerable sheep during the war. During an outfield exercise, the weapon must be slung by the side at all times, even during sleeping. The sergeants would not hesitate to “steal” the rifle from any careless soldier, and a “lost” weapon would mean extra confinement and burnt weekends.

It was a grave mistake to lose one’s rifle. Without his weapon, a soldier was like a vulnerable sheep during the war. During an outfield exercise, the weapon must be slung by the side at all times, even during sleeping. The sergeants would not hesitate to “steal” the rifle from any careless soldier, and a “lost” weapon would mean extra confinement and burnt weekends.

There were many M16-related trainings. For the fitness part, a M16 (or the heavier dummy weapon) was often used to train the endurance and the strength of the arms. In close combat trainings, a recruit also learned, in times of ammunition shortage, how to pierce the target with the bayonet fixed at the end of his M16, or hit the target with the rifle butt. In reality, it seems a better idea to lie low or retreat when your rounds are exhausted.

To many, shooting range was one of the most enjoyable activities in NS. But the excitement of firing live rounds and hitting the targets was often offset by the fear of punishment due to misfiring or other silly mistakes in the range. And not forgetting the exhausting moment during that 300m run down. A shooting range exercise usually took a day to complete. The difference between marksmen and bobo shooters became more obvious during the night shoot.

The arrival of the ninja van, with its fried bee hoon, nasi lemak and soft drinks, was perhaps the best consolation in an otherwise boring range where sections of trainees sat on long wooden benches waiting for their turns. The nickname of ninja van probably derived from its ability to find the starving troops in ulu camps and training grounds.

There were much to do after a shooting range exercise. Empty cartridges had to be picked up; rifles had to be cleared, cleaned, oiled and checked before returning to the armskote. By then, the soldiers were already shack out.

The Military Identity

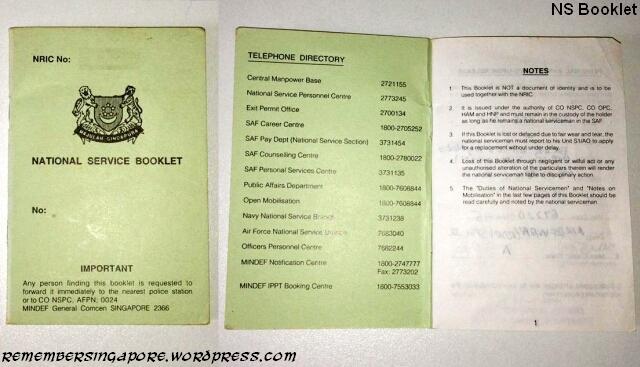

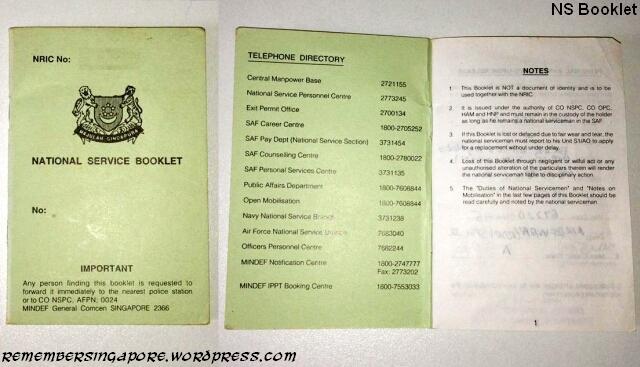

The SAF 11B is a military identification card all active national servicemen must possess. The predecessor of 11B was 11A, which was phased out two years after the introduction of 11B in 1981.

The little green NS Booklet was replaced by the convenience of the online NS Portal in the early 2000s. National servicemen no longer need to refer to their booklets on their total number of high-key and low-key ICTs.

The Defence Industry

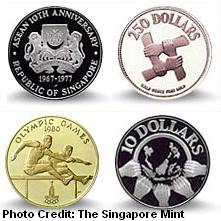

The first Minister for Defence Dr Goh Keng Swee was also the chief architect in the development of local defence-related companies to support SAF. One of its first in the industries, Chartered Industries of Singapore (CIS) was established in 1967 to supply 5.56mm ammunition rounds for the M16 rifles.

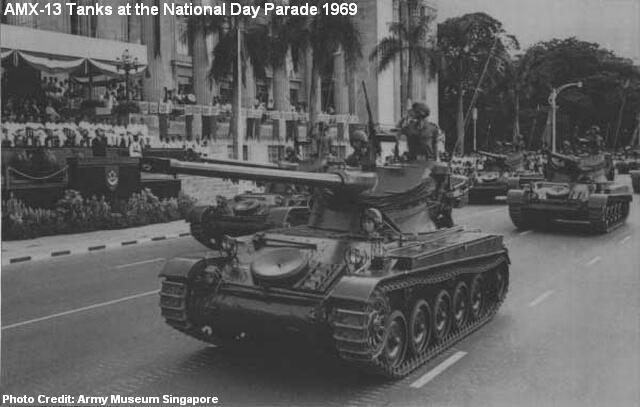

In 1969, Singapore bought 72 French-made AMX-13 tanks and 170 V200 armoured vehicles. The purchase was significant, as it kicked off a program of continuous upgradings in the history of SAF.

The late sixties and early seventies also saw the formation of Singapore Shipbuilding & Engineering (SSE), Singapore Electronic & Engineering Limited (SEEL), Singapore Automotive Engineering (SAE), Singapore Food Industries (SFI) and SAF Enterprises (SAFE).

These supporting companies provided SAF with maintenance services in communication and electronic equipment, military vehicle servicing, engineering and design, and even daily food supply to the SAF soldiers.

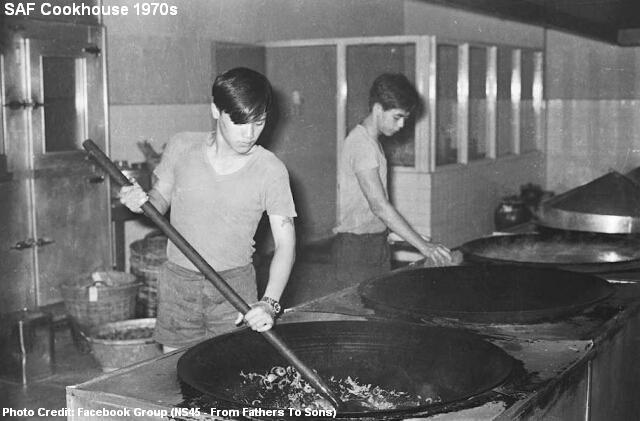

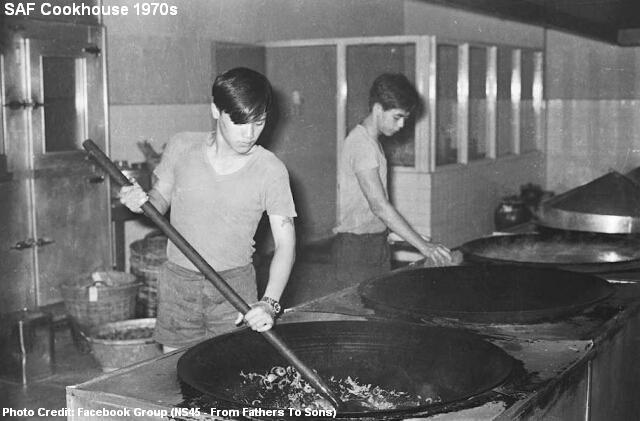

Evolution of SAF Cookhouses

The sight of military chefs, metal trays and green plastic mugs represented the days before the commercialisation of SAF cookhouses in 1997.

Hungry soldiers risked facing the wrath of cooks who were frustrated by long hours of work and oily environment, whose sweat would sometimes trickle down into the large pot while they were stirring the rice. A request for more vegetable? The emotionless cook would just dump a big load onto your tray, spilling over onto your fingers.

Daily meals of just rice, meat and vegetable were a norm. On occasional days, there would be fish ball noodles, but the noodles tasted more like rubber bands than anything else. During BMT, recruits had to take turns to wash the cookhouses and clear the garbage too. Canteen breaks became a valuable treat, as the national servicemen looked to avoid cookhouses at all cost.

The plan of outsourcing to civilian caterers was proposed as early as 1984, due to the declining number of young male Singaporeans entering the national service. However, the commercialisation of SAF cookhouses was not finalised until 1997.

Two catering companies Singapore Food Industries Manufacturing (SFIM) and Foodfare Catering (FFC) were contracted to manage 60 SAF cookhouses and provide a wide range of food to the National Servicemen, who were treated with safer food preparation and healthier choice of food.

Two catering companies Singapore Food Industries Manufacturing (SFIM) and Foodfare Catering (FFC) were contracted to manage 60 SAF cookhouses and provide a wide range of food to the National Servicemen, who were treated with safer food preparation and healthier choice of food.

The environment-friendly packaging and higher quality and lighter combat rations also made it convenient for the soldiers during their outfield exercises. The cans of baked beans, hard tack biscuits and melting chocolates were replaced by commercial off-the-shelf snacks and beverages that could be found in the supermarkets.

Today, the national servicemen enjoy different daily menus such as chicken rice, nasi bryani, pasta and even fish and chips.

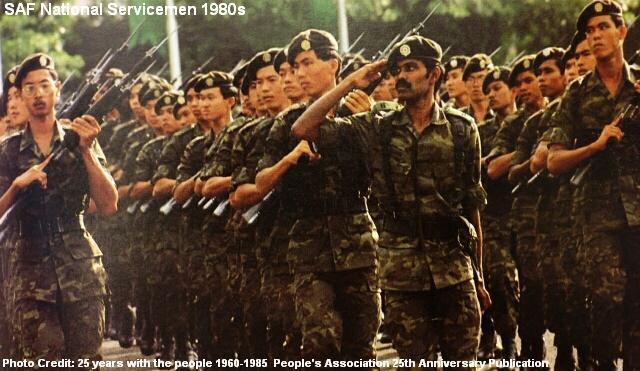

Temasek Green, Camouflaged and Pixelised

Temasek Green, the first generation of SAF combat uniform debuted in 1967, replacing the old military clothing formerly used by the British. The uniform, which was made of thick cotton and had two pockets for the shirt and three for the pants, was modified in 1977 with a darker green tone, baggier in size and an addition of two extra shirt pockets.

In 1983, the old Temasek Green uniform was replaced by the camouflaged type. Its colour fastness, however, was poor and the camouflage patterns faded easily after repeated washings. A new version made by a different material was introduced in 1985. Lighter in weight and had better air permeability, the second generation of SAF uniform lasted 25 years before being replaced by the latest 3G uniform with pixelised patterns.

With the introduction of the No.3 uniform in 1982, the parade days of the starch-stiff Temasek Green were all but memories. New monotone PT kits also made their way into SAF in 1995, replacing the old camouflaged ones.

Army Ghost Stories

Ghost stories always ranked high in the list of common topics among national servicemen during chit chatting sessions, especially if they were stationed in an old ulu camp.

The most famous of all was the legendary three-door bunk of Charlie Company at Pulau Tekong. The story managed to find its way between batches and generations even though the unfortunate incident happened more than 30 years ago and the creepy bunk no longer exists today.

Prowling around the old Tekong camp at night was never fun, especially when there were rife rumours of a weeping female ghost in white dress sitting on the Jacob’s Ladder. Another popular ghost story in NS was the spirit of an old man walking around at night with his granddaughter. Their footsteps could be heard from afar, but the next moment you could sense them standing beside your bed.

“This one not asleep yet!” the granddaughter mocked, pointing to those who closed their eyes tightly pretending to sleep.

What about the famous haunted White House at Nee Soon Camp? Sounds were always heard at night, yet the building was empty when the prowlers checked it out. Or that poor soul of a soldier who had to return to the same level of the building every night to repeat his suicide. And when a pack of dogs gathered and howled at the chin up bar, there were whispers that it was due to the spirit of a national serviceman who hanged himself at the bar many years ago.

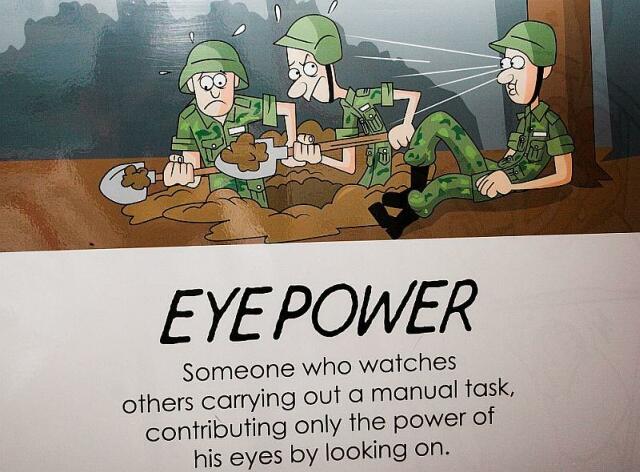

Colourful NS Lingo

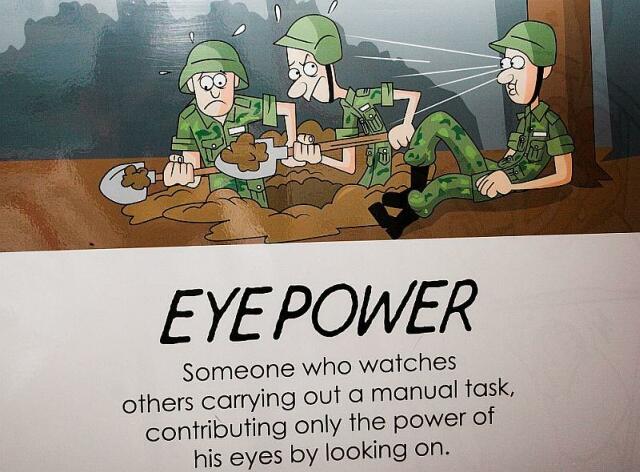

Singapore is a place full of acronyms and abbreviations, such as PIE (Pan-Island Expressway), ERP (Electronic Road Pricing) and MOE (Ministry of Education). Likewise, SAF itself has many abbreviations. With the addition of our unique Singlish, a list of colourful NS lingo is born.

Hokkien used to be a common language used during SAF trainings. It was, however, banned in October 1978. Only English, Malay and Mandarin were allowed. But as the old army saying goes: “Do whatever you want, just don’t get caught“, the widespread usage of Hokkien, especially the vulgarities, has continued to this day.

Hokkien used to be a common language used during SAF trainings. It was, however, banned in October 1978. Only English, Malay and Mandarin were allowed. But as the old army saying goes: “Do whatever you want, just don’t get caught“, the widespread usage of Hokkien, especially the vulgarities, has continued to this day.

Some common phrases seemed to be frequently used by most instructors. Eg, during a run, the instructors like to say sarcastically: “Walk some more! Never mind, take your time” or “My grandmother can run faster than you“.

During a tekan session: “Whole lot knock it down!“, “I can’t hear you!“, “Shack right? Cannot think properly isn’t!?“. Other favourite phrases include “You think I thought who confirms?“.

ROD (Run Out Date), arguably the most significant acronym to any national serviceman, was changed to ORD (Operational Ready Date) in July 1994.

NS Sing-a-Long

“Any Sweat? No Sweat! Chicken feed, ha ha all the way!”

Little was known of how the NS songs came about. Some were perhaps passed down by the British during the colonial era, while others might be created by some talented local national servicemen in the seventies and eighties. Nevertheless, the songs aimed to boost the morale of the soldiers during a run or a route march. Who forget the 24km BMT graduation route march, where everyone sang in high spirits (at the start) and encouraged each other to complete the feat?

“C130 rolling down the street

Airborne rangers take a little trip

Stand up hook up shuffle to the door

Jump right down by the count of 4

If this chute doesn’t open wide

I have another one by my side

If this one doesn’t open too

Then you all can see me die

If I die in a Russian front

Bury me with a Russian gun

If i die in a Vietnam war

Send me back to Singapore

Tell my major I’ve done my best

Silver wings upon my chest

Tell my mama I’ve done my best

Now its time to take a rest”

“Purple light, in the army

That is where, I wanna be

Infantry, best companion

With my rifle and my buddy and me

SOC, sibei jialat

Log PT, lagi worse

Everyday, doing PT

With my rifle and my buddy and me

Booking out, saw my girlfriend

Holding hands, with another man

Broken heart, back to army

With my rifle and my buddy and me

ORD, back to studies

Get degree, so happy

Can’t forget, still remember

With my rifle and my buddy and me

Purple light, in the war front

There is where, my body dies

If I die, would you bury

With my rifle and my buddy and me”

“Far far away in the South China Sea

I left a girl, with tear in her eyes,

I must go where the great men fights ya

A soldier has to fight the front because he love his land ya

A soldier has to fight even his has to die!

Coz we are the one who fight the front

And we are the one who holds the gun,

We are mighty warriors from this land ya

Alpha warriors marching in hoorah hoorah

Alpha warriors marching in hoorah hoorah

Coz we are the one who fight the front

And we are the one who holds the gun,

We are mighty warriors from this land ya”

“Everywhere we go-o

People want to know-o

Who we are

Where we come from

So we tell them

We are from (name of platoon/company/battalion)

Mighty, mighty (name of platoon/company/battalion)

And if they can’t hear us

We sing a little louder”

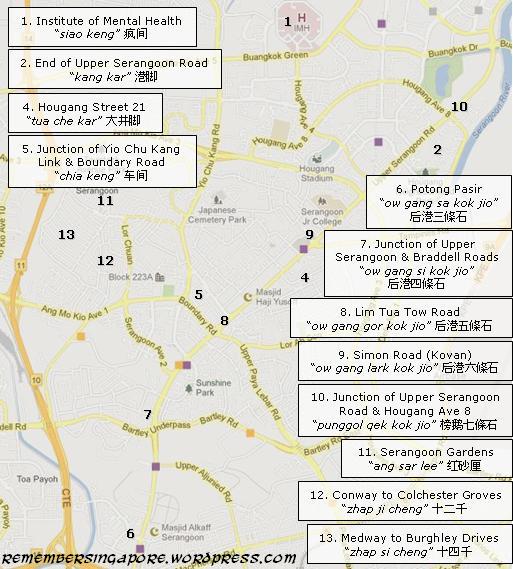

Army Camps in Singapore

There are over 100 army camps and military bases in Singapore. Many were built by the British during the colonial era, while the rest were formed by the Singapore Armed Forces after independence. Below are brief descriptions of some of the old and former camps in Singapore.

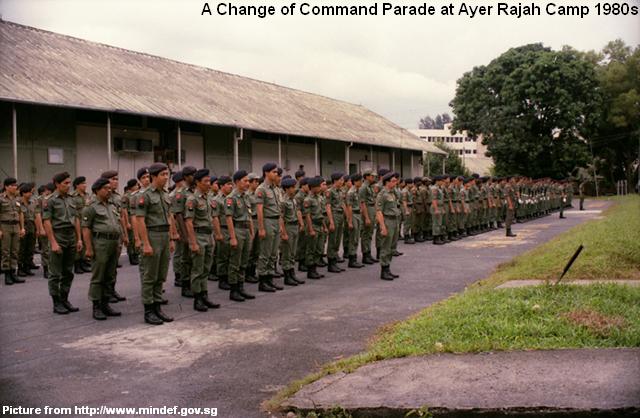

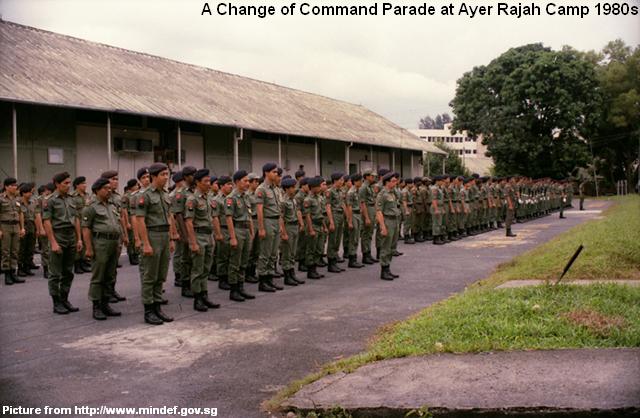

Ayer Rajah Camp (1940s-2010)

Located at Portsdown Road, the Ayer Rajah Camp was well known as a servicing and vehicle maintenance camp. It was formerly part of the British’s Pasir Panjang Complex that also included the Gillman Barracks and Alexandra Camp. The camp was first home to the British Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers, which provided maintenance services to the British military vehicles before the Second World War.

After the war, the camp was taken back from the Japanese forces and placed under British control for another 27 years before they departed in 1971. It was then handed over to SAF’s Ordnance Maintenance Base (OMB). In the eighties, the Headquarters (HQ) Maintenance and Ordnance Engineering Training Institute (OETI) moved in to share the premises with OMB, which was reorganised as General Support Maintenance Base (GSMB).

In 2010, the camp was closed and its site was returned to the State. Its premises will be leased to MediaCorp in 2014.

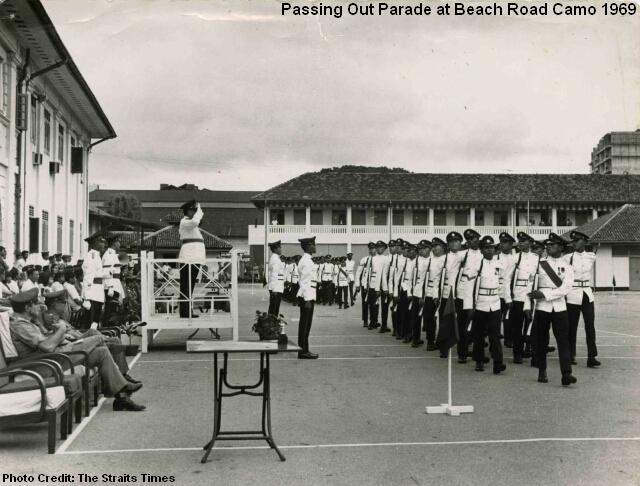

Beach Road Camp (1930s-2000)

One of the few former military camps situated in the City, the Beach Road Camp was built on reclaimed lands and originally standing just beside the coastline. Its Art Deco-styled buildings were functioning as the headquarters for the Singapore Volunteer Corps (SVC), which was formerly located at Fort Fullerton.

Beach Road Camp played a significant military role in the early days of Singapore’s independence. It served as the main registration centre for the early batches of NS enlistees, and was home to several SAF units such as the infantry regiment, signal unit and provost company. The People’s Defence Force (PDF), formerly SVC, retained the camp as its headquarters.

By the mid-nineties, it became apparent that Beach Road Camp would be shifted due to its location in the prime land district. In 2000, the camp was officially shut down. Its three colonial buildings Block 1, 9 and 14 were given conservation status in 2002, while its plot of land, along with the former NCO club, was sold to private developers of hotels, offices and residences.

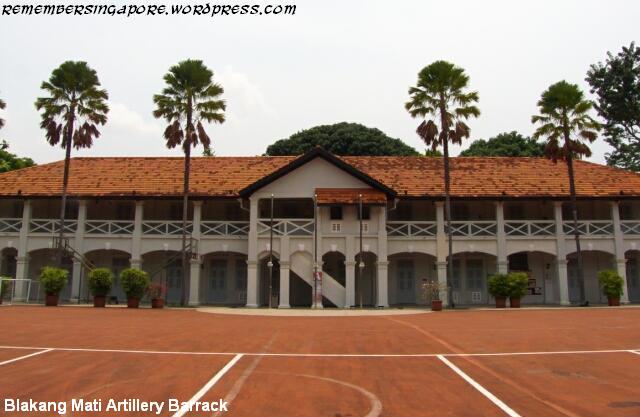

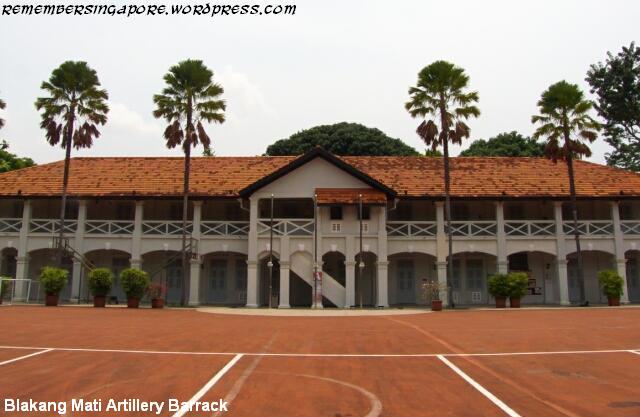

Blakang Mati Artillery Barracks (1910-1972)

Built in 1910, the Blakang Mati Artillery Barracks on present-day Sentosa was part of the British’s defensive facilities for the southern coastline of Singapore. The island and the barracks, however, fell to the Japanese forces during the Second World War, and were used as a prisoners-of-war camp.

Singapore’s first artillery division First Singapore Regiment Royal Artillery was established at Blakang Mati Artillery Barracks in 1948. It also housed the Singapore Naval Volunteer Force, School of Maritime Training and Naval Medical School after Singapore’s independence. But SAF’s control of the barracks lasted only until 1972, when the government decided to develop the island for leisure and tourism.

The barracks were abandoned for many years until recently, when the site was put up for sale for a hotel development project.

Changi Command Barracks (1935-1990s)

Standing proudly on Fairy Point Hill, the former Changi Commando Barracks was once an integrated part of the British’s naval and air defence strategy against any potential invasions at the eastern part of Singapore. Constructed in 1935, it was originally a command building for the British Royal Engineers.

In 1971, the vicinity became part of the Commando Unit’s premises when the SAF elite troops were relocated from Pasir Laba Camp to Changi Camp. Two years later, the unit was strengthened with its first NS battalion, supported by a new school and headquarters. The iconic colonial building on Fairy Point Hill was used as the HQ office for the Commandos.

When Hendon Camp was officially inaugurated in 1993 as the new home for the Commandos, Changi Commando Barracks was abandoned for many years. In 2002, it was given the conservation status, and the premises are now part of a new hotel development project.

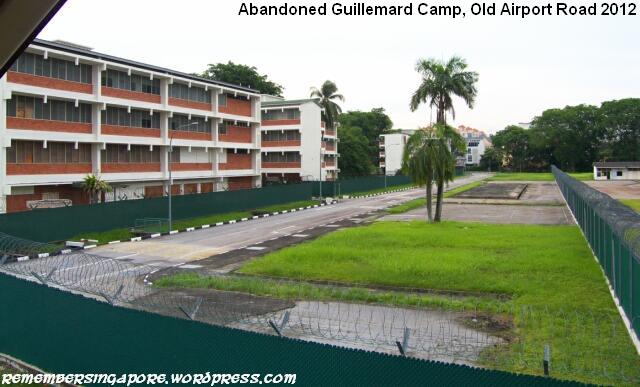

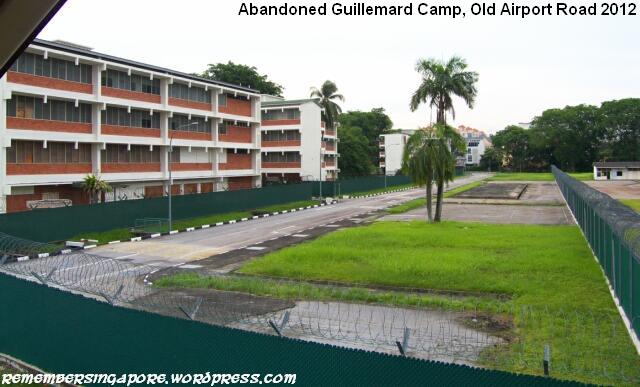

Guillemard Camp (1969-2003)

The former Guillemard Camp was home to 1SIR, Singapore’s first military unit. It was established at the start of 1969 for the relocation of 1SIR from Taman Jurong Camp. Generations of recruits had gone through intensive infantry training at the small Guillemard Camp for past 30-plus years.

The camp stayed relatively the same despite the changes in its surroundings, where blocks of residential flats popped up along Old Airport Road and Dakota Crescent. Due to the limitation in space and aging training facilities, its operations were finally ceased in in 2003, with 1SIR shifted to Mandai Hill Camp. The plot of land has since been reserved for future housing development.

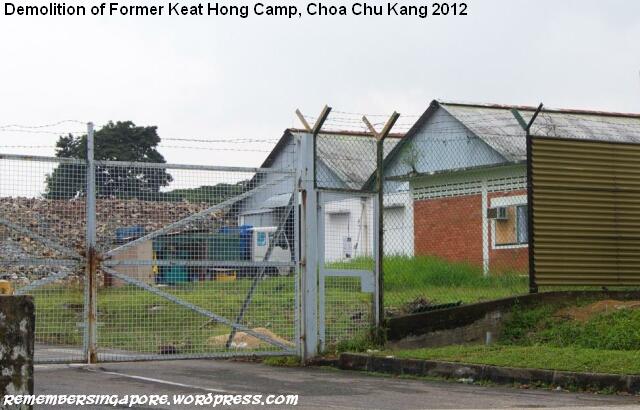

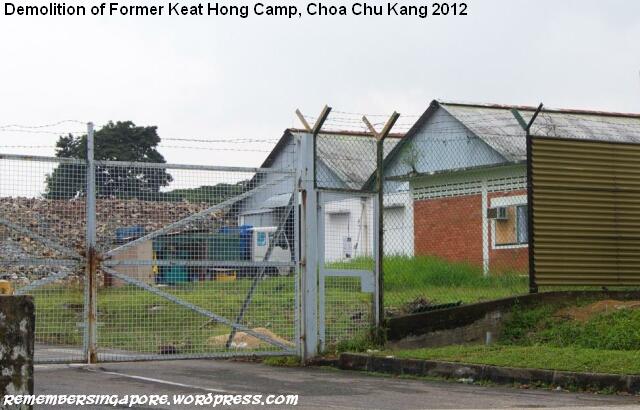

As the population increases, the growing need for more residential development means those old redundant camps have to make way. In recent years, the likes of Haig Road Camp, (Old) Keat Hong Camp and Simon Road Camp were demolished for the construction of public flats and condominiums. As the old barracks were being torn down, they vanished together with the memories of many generations of national servicemen once stationed at those camps.

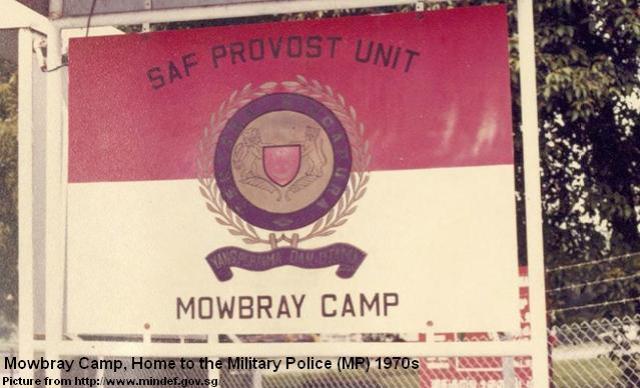

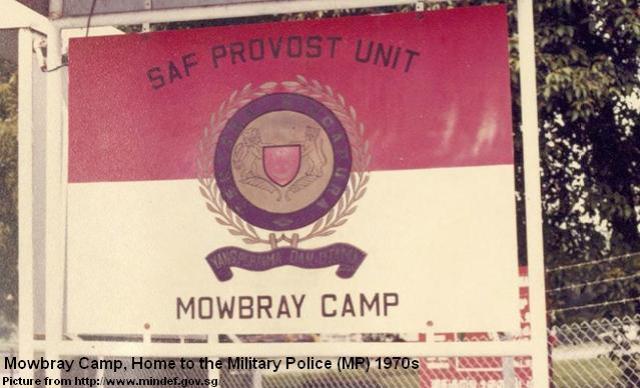

Mowbray Camp (Old) (1937-2002)

The old Mowbray Camp at the junction of Ulu Pandan Road and Clementi Road was a former British camp that used to house its guard contingent. It was, however, more well-known for being the home of the SAF Provost Unit between 1971 and 2002. SAF Provost Unit was first established in 1966 at Beach Road Camp, before moving to Hill Street Camp and finally settled at Mowbray Camp for 31 years.

The mentions of MP (Military Police) and DB (Detention Barracks) had struck fear into the hearts of many generations of national servicemen. SAF’s first military detention cells were set up at Beach Road Camp together with the SAF Provost Unit in 1966. By the eighties, there was a total of four major detention barracks in Singapore (Kranji, Nee Soon, Changi and Tanglin). In 1987, the SAF Detention Barracks was officially opened as a centralised military prison, replacing the other old detention barracks.

Mowbray Camp was also home to Home Team’s canine unit. The Police Dog Unit was stationed here as early as the 1950s, before being linked up with the Customs & Excise Department’s canine unit (in 1987), the Prisons Department’s canine unit (1995) and the Singapore Civil Defence Force’s Rescue Dog Section (1997).

In 2002, the SAF Provost Unit moved to the new Mowbray Camp at Choa Chu Kang Way.

Nee Soon Camp (1934-Present)

Located opposite Kangkar in the olden days, Nee Soon Camp was first set up by the British in 1934 as one of the military bases in the northern part of Singapore. The recruits of first Singapore Infantry Battalion were trained at Nee Soon Camp when Singapore established its own military forces in 1957.

The establishment of Nee Soon Camp brought prosperity to its surroundings, increasing the population and commercial activities. In 1930, prominent Chinese businessman Lee Kong Chian (1893-1967) saw the opportunities and bought the row of 24 shophouses opposite Nee Soon Camp, renting them out as provision shops, bakeries, barber salons, tailor shops and others.

Nee Soon Camp functioned as a school of BMT until the late 1990s. It received major revamp in the 2000s, with many of its old colonial buildings demolished. Today, there is even a condominium standing near the entrance of Nee Soon Camp, beside the row of shophouses that are famous for their military apparel and paraphernalia.

Selarang Camp (1938-Present)

The British built Selarang Camp at Loyang, in the eastern part of Singapore, in 1938. It was used by the Scottish Battalion but was occupied by the Japanese during the Second World War. During the Japanese Occupation, as many as 15,000 Australian Prisoners-of-War (POWs) were imprisoned at Selerang Camp. In 1942, the Japanese forced the POWs onto the parade square for five days without water and sanitation, in a bid to force the prisoners to agree not to escape. This was later known as the “Changi Incident”.

After the Second World War, Selarang Camp was used as a base by the Australian Army units from the ANZUK, which was made up of troops from Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. In 1971, the camp was officially handed over to SAF, and had housed the 9 Division of the Armed Forces since 1984. Its premises were given an extensive upgrading at a cost of $50 million in 1991. Many of its old colonial buildings were demolished to be replaced by new modern complexes.

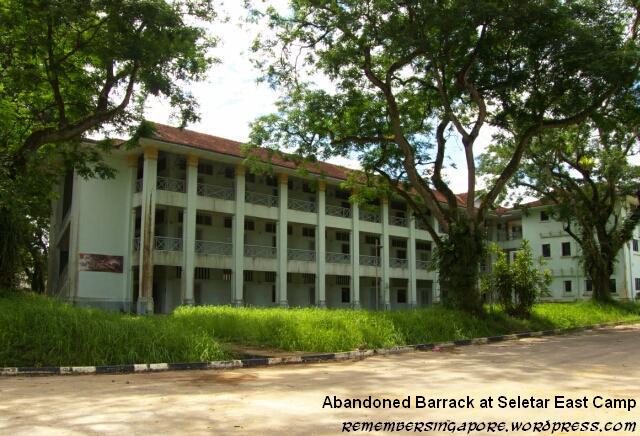

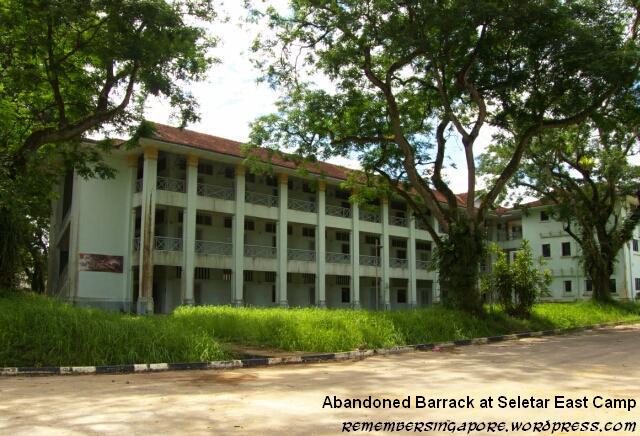

Seletar Camp (1920s-Present)

Seletar Camp and its airbase were largely constructed in the 1920s as British military facilities for air travel and air defence. The premises were officially owned by the Royal Air Force in 1930 but fell to the hands of the Japanese forces during the Second World War. The Japanese navy captured Seletar Airbase in 1942 and renamed it as Seretar Hikojo.

After the war, the British repossessed Seletar Camp but the airbase no longer boasted the largest in Singapore, being replaced by the new airfield at Changi. SAF took over Seletar Camp in 1971, and maintained restricted public access to its eastern part of the camp. The western part was open to public and commercial aircraft.

Due to the Seletar Aerospace Park project since the late 2000s, the quiet rustic Seletar Camp had gone through tremendous changes, with many of its old colonial buildings demolished.

Tanglin Barracks (1861-1989)

Tanglin Barracks were one of the oldest camps in Singapore. Built in 1861, it was situated in a former nutmeg plantation, functioning as a base for the British garrison infantry battalion. After SAF took over it in 1971, the camp was designated as the headquarters for the Ministry of Defence and the Central Manpower Base. Since the early 2000s, the premises around the vacated Tanglin Barracks had seen significant development as a hub for lifestyle, fine dining and cultural arts.

The list consists of other camps not mentioned above:

Saluting all former and current NS personnel!

Published: 01 May 2013

Updated: 19 October 2014

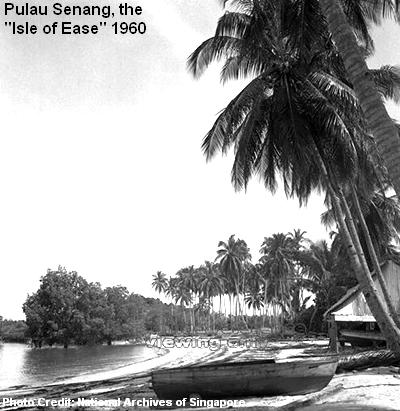

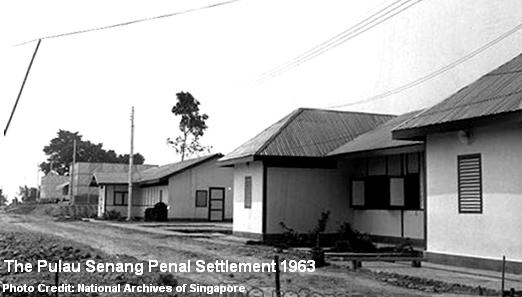

The outdated prison system soon could not cope with the continuous arrests. Its overcrowding and hygienic issues forced the authority to explore new ideas and solutions. By early 1960, a Pulau Senang Settlement proposal was drawn; its objective was to solve the existing issues and also to help the gangsters work their way back to the society through hardship and sweat.

The outdated prison system soon could not cope with the continuous arrests. Its overcrowding and hygienic issues forced the authority to explore new ideas and solutions. By early 1960, a Pulau Senang Settlement proposal was drawn; its objective was to solve the existing issues and also to help the gangsters work their way back to the society through hardship and sweat. At least one person, Irishman Daniel Stanley Dutton, held this belief. A born leader and the superintendent of the Prison Department, Dutton strongly believed that no man was born evil, and a second chance should be given to those who were willingly to change for the better. It was a noble aspiration, but Dutton’s iron-fist rule also meant that his prisoners were subjected to his harsh disciplinary methods, one of the reasons that might have incited the riot.

At least one person, Irishman Daniel Stanley Dutton, held this belief. A born leader and the superintendent of the Prison Department, Dutton strongly believed that no man was born evil, and a second chance should be given to those who were willingly to change for the better. It was a noble aspiration, but Dutton’s iron-fist rule also meant that his prisoners were subjected to his harsh disciplinary methods, one of the reasons that might have incited the riot.

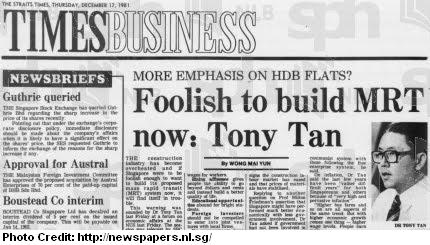

Then-Trade and Industry Minister Dr Tony Tan suggested more emphasis to be placed on the construction of public housing instead of a mass rapid transit system, as Singapore was facing a labour shortage and rising building costs. The building of Changi Airport also took a toil on the construction resources in the previous five years between the late seventies and early eighties.

Then-Trade and Industry Minister Dr Tony Tan suggested more emphasis to be placed on the construction of public housing instead of a mass rapid transit system, as Singapore was facing a labour shortage and rising building costs. The building of Changi Airport also took a toil on the construction resources in the previous five years between the late seventies and early eighties.

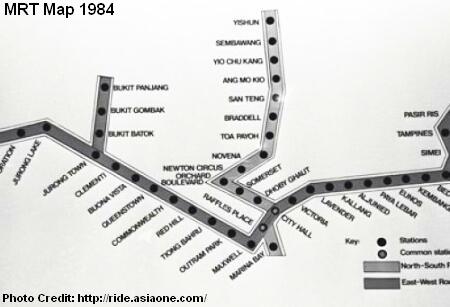

There were glaring differences in the early maps. The station codes were absent, and there was no Khatib station. Instead, a Sembawang station stood between Yishun and Yio Chu Kang. The stations of Bishan, Newton and Orchard were also listed as San Teng, Newton Circus and Orchard Boulevard respectively.

There were glaring differences in the early maps. The station codes were absent, and there was no Khatib station. Instead, a Sembawang station stood between Yishun and Yio Chu Kang. The stations of Bishan, Newton and Orchard were also listed as San Teng, Newton Circus and Orchard Boulevard respectively.

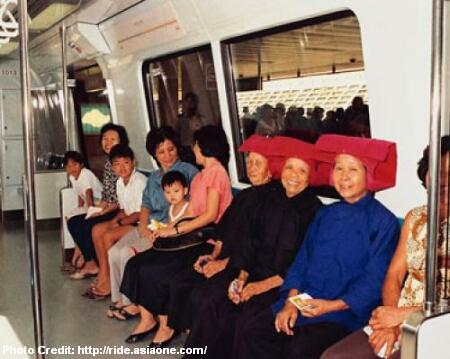

One of the first MRT trains arrived at the Bishan Depot in July 1986. A commemoration ceremony was held to mark the significant event, and was officiated by Dr Yeo Ning Hong, then-Minister for Communications and Information.

One of the first MRT trains arrived at the Bishan Depot in July 1986. A commemoration ceremony was held to mark the significant event, and was officiated by Dr Yeo Ning Hong, then-Minister for Communications and Information.

On 3rd March 2003, a 23-year-old driver lost control of his Mercedes Benz along Lentor Avenue, crashing through the fence and landing onto the tracks. A northbound train could not stop in time, but slowed down sufficiently to avoid a major collision. There were some injuries reported and a three-hour disruption in service.

On 3rd March 2003, a 23-year-old driver lost control of his Mercedes Benz along Lentor Avenue, crashing through the fence and landing onto the tracks. A northbound train could not stop in time, but slowed down sufficiently to avoid a major collision. There were some injuries reported and a three-hour disruption in service.

The security of the SMRT depots at Changi and Bishan was twice breached in May 2010 and October 2011, resulting in trains being vandalised with graffiti. The first vandalism was committed by a Swiss expatriate Oliver Fricker, 32, and his British accomplice, Dane Alexander Lloyd. After the repeated incident of vandalism, SMRT was fined a maximum of $50,000 by LTA.

The security of the SMRT depots at Changi and Bishan was twice breached in May 2010 and October 2011, resulting in trains being vandalised with graffiti. The first vandalism was committed by a Swiss expatriate Oliver Fricker, 32, and his British accomplice, Dane Alexander Lloyd. After the repeated incident of vandalism, SMRT was fined a maximum of $50,000 by LTA.

It is simply known as Captain SMRT. The superhero, donned in red and possibly the only second superhero in Singapore after VR Man (created by the Television Corporation of Singapore (TCS) in 1998), was created to promote the safe behaviour of commuters and the train system’s safety measures, such as the emergency exits.

It is simply known as Captain SMRT. The superhero, donned in red and possibly the only second superhero in Singapore after VR Man (created by the Television Corporation of Singapore (TCS) in 1998), was created to promote the safe behaviour of commuters and the train system’s safety measures, such as the emergency exits.

1983

1983

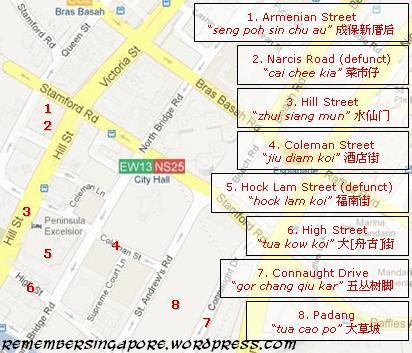

In the 19th century, Tan Seng Poh 陈成保 (1830-1879), a wealthy Teochew opium farm owner as well as a municipal commissioner and Justice of Peace, built a large mansion at Loke Yew Street near Fort Canning. The house was so prominent that the local Chinese named the adjacent Armenian Street as “seng poh sin chu au” (成保新厝后, at the back of Seng Poh’s new house).

In the 19th century, Tan Seng Poh 陈成保 (1830-1879), a wealthy Teochew opium farm owner as well as a municipal commissioner and Justice of Peace, built a large mansion at Loke Yew Street near Fort Canning. The house was so prominent that the local Chinese named the adjacent Armenian Street as “seng poh sin chu au” (成保新厝后, at the back of Seng Poh’s new house).

The history of local military regulars has gone a long way back. In April 1955, Singapore was given its first Legislative Assembly Election, with David Marshall (1908-1995) served as the First Chief Minister of Singapore. When Lim Yew Hock took over the partial self-government a year later, his hardline approach against the communists persuaded the British to grant Singapore more autonomy.

The history of local military regulars has gone a long way back. In April 1955, Singapore was given its first Legislative Assembly Election, with David Marshall (1908-1995) served as the First Chief Minister of Singapore. When Lim Yew Hock took over the partial self-government a year later, his hardline approach against the communists persuaded the British to grant Singapore more autonomy. The officers and men were later based at Ulu Pandan Camp, but it took six years before 1SIR reached its full battalion strength of over 800 men. The early roles of 1SIR was mainly to engage internal security and maintain civil order with the police.

The officers and men were later based at Ulu Pandan Camp, but it took six years before 1SIR reached its full battalion strength of over 800 men. The early roles of 1SIR was mainly to engage internal security and maintain civil order with the police.

With the successful establishment of the additional infantry battalions and the new SAF Training Institute, other facilities such as the School of Artillery and School of Signals soon followed. In the late sixties, SAF also introduced its first scholarship program to attract the brightest talents to join the military as their careers. The university study fees and living expenses were offered in exchange for an eight-year bond with the armed forces.

With the successful establishment of the additional infantry battalions and the new SAF Training Institute, other facilities such as the School of Artillery and School of Signals soon followed. In the late sixties, SAF also introduced its first scholarship program to attract the brightest talents to join the military as their careers. The university study fees and living expenses were offered in exchange for an eight-year bond with the armed forces.

Unlike today, the past national servicemen had to do all the area cleanings themselves, taking turns to wash the toilets, empty the drains and clear the dry leaves on the carparks. Beds had to be made each morning with wrinkle-free bedsheets. The boots must be polished gilat gilat, and displayed neatly along with the shoes and slippers by the beds. The items in the cupboards should be placed in their orders, with the shelves kept dust-free.

Unlike today, the past national servicemen had to do all the area cleanings themselves, taking turns to wash the toilets, empty the drains and clear the dry leaves on the carparks. Beds had to be made each morning with wrinkle-free bedsheets. The boots must be polished gilat gilat, and displayed neatly along with the shoes and slippers by the beds. The items in the cupboards should be placed in their orders, with the shelves kept dust-free.

Two catering companies Singapore Food Industries Manufacturing (SFIM) and Foodfare Catering (FFC) were contracted to manage 60 SAF cookhouses and provide a wide range of food to the National Servicemen, who were treated with safer food preparation and healthier choice of food.

Two catering companies Singapore Food Industries Manufacturing (SFIM) and Foodfare Catering (FFC) were contracted to manage 60 SAF cookhouses and provide a wide range of food to the National Servicemen, who were treated with safer food preparation and healthier choice of food.

Hokkien used to be a common language used during SAF trainings. It was, however, banned in October 1978. Only English, Malay and Mandarin were allowed. But as the old army saying goes: “Do whatever you want, just don’t get caught“, the widespread usage of Hokkien, especially the vulgarities, has continued to this day.

Hokkien used to be a common language used during SAF trainings. It was, however, banned in October 1978. Only English, Malay and Mandarin were allowed. But as the old army saying goes: “Do whatever you want, just don’t get caught“, the widespread usage of Hokkien, especially the vulgarities, has continued to this day.