The rapid urbanisation of Singapore in the past four decades has seen hundreds of villages demolished and the lands freed up for redevelopment. The life of many Singaporeans of the last generation changed dramatically as they shifted from their kampong to the high-rise public flats. The days of living in dilapidated wooden attap houses with hygienic concerns and limited supplies differed greatly from the comfort of the public housings fitted with electricity, water and gas.

On the other hand, the community, or kampong, spirit is lost when more people tends to coop themselves up in their own flats nowadays, and interaction with neighbours become a rarity. Children of the newer generation have also lost the chance to come in contact with nature; many of them probably have not seen a live rooster in their life.

Nevertheless, there is still one kampong existing on mainland Singapore today, although the land it is standing on is currently facing the prospect of being acquired by the government.

Singapore’s Last Kampong

Kampong Lorong Buangkok, established in 1956, has a mixture of Chinese and Malay residents living in harmony. There are about 28 single-storey zinc-roof houses here, on a landsize roughly equaled to three football fields. The land belongs to the Sng family, who lives here among the residents and collects only small tokens from the other families as rental fees.

Hidden in a small stretch off Yio Chu Kang Road, the forgotten hamlet has a rustic and rural environment filled with plants of tapioca, papaya, guava and yam. It is not uncommon to see lizards or squirrels scurrying past the dirt roads, or find guppies swimming in the nearby Sungei Punggol, where part of it has now become a canal. Since 2000, the kampong’s surrounding has already changed tremendously. High-rise flats at Buangkok Green and Fernvale, and a newly constructed jogging track, have now encircled Kampong Lorong Buangkok.

The Recent Demolition

Khatib Bongsu was the most recent kampong to be demolished, in 2007. It was situated in the forested area at Yishun, near the mouth of Sungei Khatib. The land had been designated to be military training ground by the Ministry of Defence (Mindef) since the early nineties, but many residents of the kampong were reluctant to shift. By late 2006, there were only two persistent residents left at Khatib Bongsu.

During its heydays, there were numerous zinc-roof houses at Khatib Bongsu, artificial ponds used for prawn rearing and wooden jetties built by the river. Some villagers used to rent generators to power their electrical appliances and collect rainwater for washing purposes. The daily meals were simple cooked with the fish and prawns caught from the waters, or a 30-minute ride by bicycle to the nearest kopitiam at the modernised Yishun.

Khatib Bongsu was also a favourite hunt for the nature-lovers and adventure groups, but the demolition of the kampong and the closure of the track off Yishun Avenue 6 by 2007 had put a stop to the activities that included fishing, bird-watching, trekking and durian-picking.

(Editor’s Note: Special thanks to photography expert Kelvin Lee for these beautiful rare photos of Khatib Bongsu taken in 2005)

Natives, Immigrants and the British

It is difficult to determine exactly how many kampong ever existed in Singapore. Prior to Sir Stamford Raffles’ arrival, the aboriginal orang laut led a nomadic life living at the swampy areas, the mouth of the rivers and some of the small islands. The earliest was perhaps the orang selat who inhabited near the waters of the present-day Keppel Harbour. Others include orang seletar at Seletar River, orang kallang at Kallang River and orang gelam at the Singapore River. By 1850s, the majority of orang laut was either moved to live in kampong on the mainland of Singapore or relocated to Johor. Orang kallang, sadly, was wiped out in 1848 due to a breakout of smallpox.

After Raffles established Singapore as a British colony, an urban development plan known as Jackson Plan was drawn in 1822. At the downtown core along the Singapore River, four ethnic settlement areas were designated for the main races then, namely the European Town for the Europeans, Eurasians and rich Asians, Kampong Glam for the ethnic Malays, the Muslims and the Arabs, the Chinese Kampong (or Chinatown) for the Chinese immigrants and the Chulia Kampong for the Indian community. The racial segregation was later abandoned but the layout of each district had became what the city area is today.

The Kangchu System

As the downtown core became crowded, some residents moved to the other rural parts of Singapore, establishing villages and plantations, especially near the mouths of the rivers where the soils were fertile. Like other parts of Malaysia, many Chinese agricultural settlers set up pepper and gambier plantations along the river banks in the 19th century. The village chief was known as kangchu 港主 (the lord of the river), which explains the names of three prominent districts in Singapore. The areas at present-day Lim Chu Kang, Choa Chu Kang and Yio Chu Kang were formerly the kangchu systems headed by the Lim, Choa and Yio (Yeo) clans. There were also Chan Chu Kang (曾厝港), Tan Chu Kang (陈厝港) and Lau Chu Kang (刘厝港); while Chan Chu Kang became Nee Soon Village, Tan Chu Kang and Lau Chu Kang ceased to exist.

By 1917, the British colonial government decided to abolished the kangchu system due to the influence of some Chinese tycoons, their links to secret societies and the widespread social vices such as gambling, opium and prostitution. The Chinese later moved to set up rubber, pineapple and other plantations.

Kampong in Northern Parts of Singapore

Yishun

Nee Soon Village (formerly Chan Chu Kang) was one of the oldest Chinese kampong (pronounced as gum gong in Teochew) in Singapore. It existed as early as 1850, and was later renamed as Nee Soon Village after rubber magnate Lim Nee Soon (1879 – 1936). Lim Nee Soon and his son Lim Chong Pang (1904 – 1956) contributed massively in the development of the northern part of Singapore, thus many areas and roads in modern-day Yishun bear their names. Chong Pang Village was originally called Westhill Village before its renaming in 1956. It was located in present-day Sembawang New Town and was predominantly an Indian village until the mid-1950s. Chong Pang Village was later demolished in 1989 to make way for the development of Sembawang New Town. The current Chong Pang housing estate in Yishun, built in 1981, is not the former Chong Pang Village.

Other Chinese villages in the Nee Soon district were Bah Soon Bah Village (named after the Baba name of Lim Nee Soon), Hup Choon Kek Village (built in 1930s), Chye Kay Village (财启村), Kum Mang Hng Village, Hainan Village, De Lu Shu Village, Kampong Sah Pah Siam and Kampong Telok Soo (or Kampong Kitin). After the collapse of the rubber industry in 1935, the villagers, mostly Hokkiens and Teochews, switched to vegetable and fruit farming, orchid farming, fish and prawn breeding, pineapple and coconut planting and pig and poultry rearing. Most of the residents were resettled in Ang Mo Kio and Tampines when Yishun New Town was developed in 1977.

Heng Ley Pah Village (or fondly called Phua Village) was made up of a group of Hokkiens headed by the Phua clan, whose ancestors came to Singapore in the late 19th century from Nan An County of China. They first settled at Upper Thomson and Yio Chu Kang, before eventually moved to Lorong Handalan (present-day Springleaf estate), Lorong Persatuan and Lorong Sunyi (all three roads were now defunct) in 1914. The kampong became known as Heng Ley Pah, named after a rubber plantation nearby. The Phua clan built a temple known as Hwee San Temple for their religious and social needs, as well as a mandarin primary school called Xing Dun in 1936. The fortune of Heng Ley Pah Village declined in the seventies, and by 1990, most of its residents had moved into Yishun New Town.

The Malay population of the old Nee Soon estate was not particularly large, with some of them living at Kampong Jalan Mata Ayer along Sembawang Road. The villagers built a mosque called Masjid Ahmad Ibrahim that is still standing today, located at Jalan Ulu Seletar. Other villages would be scattered along the coastlines of Sungei Seletar (now Lower Seletar Reservoir), engaging in farming as well as fishing.

Sembawang

Kampong Wak Hassan was one of the most recent villages that vanished due to urbanisation, long after other villages in the same region were demolished, such as Sembawang Village, Kampung Lubang Bom, Kampung Hailam, Kampong Tanjong Irau and Sungei Simpang Village.

Housing several Malay and Chinese families, it lasted until 1998 before it was forced to make way for the development of area beside Sembwang Shipyard. The nearby Mihad Jetty, which was used by the villagers to park their boats, was torn down along with the kampong.

Punggol

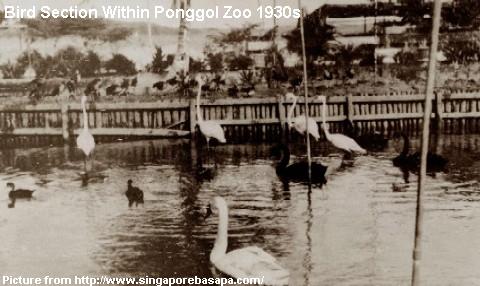

Punggol of the old days was a large rural land of farms and forests. At the tip of northern Punggol, where the Punggol Jetty is located, once existed a Malay kampong called Kampong Punggol. It was settled by the families of the fishermen who plied their trade at Sungei Dekar. One of the oldest settlements in Singapore, the kampong was believed to be more than 200 years old, existing even before Raffles’ arrival.

By the mid-19th century, the Chinese began to settle in Punggol, establishing a marketplace at the 8th milestone of Punggol Road for trading of fish, vegetable and fruits.

Flanked by two rivers in Sungei Punggol and Sungei Serangoon, there were also many fishermen living near the river banks. A Teochew Kangkar Village was once located at the end of Upper Serangoon Road, near the mouth of the Serangoon River where it was filled with fishing boats and sampans. Consisted of a bustling wholesale fish market, the coastal kampong was demolished in 1984 to make way for the Ponggol Fishing Port, which itself was replaced by Senoko Fishing Port in 1997.

Further down the stream, a small village was developed in 1956 at Kampong Lorong Buangkok, which is now the last kampong in mainland Singapore. After 1979, Punggol became one of the two designated places in Singapore that allowed pig farms. The other place was Lim Chu Kang.

Jalan Kayu/Seletar

Built in 1928, the road of Jalan Kayu was the main access to the Seletar Air Base built by the British in the twenties. There were probably settlements prior to the development of the airbase but Jalan Kayu Village prospered due to the influx of RAF (Royal Air Force) personnel who lived in the colonial houses at Seletar. The British servicemen would visit the pasar malam, food stalls, tailors and barber shops at Jalan Kayu, providing businesses for the small community. Other residents would earn a living from their vegetable farms, which were a common sight at Jalan Kayu in the 1950s.

Woodlands/Kranji/Mandai

In 1993, Kampung Wak Selat was thrown into the media spotlight when the government insisted the demolition of the Malay village of about 70 houses. Established in 1947 and consisted of facilities such as water supply, a football ground, a prayer house and a simple wooden mosque, the kampong was located along the former Malayan railway tracks between Kranji Road and Sungei Mandai Besar. Most of the residents chose to move and live in the nearby Marsiling housing estate. Today, it is replaced by a JTC (Jurong Town Corporation) factory.

A coastal Malay kampong near the Causeway, Kampong Lorong Fatimah struggled to exist until 1989, when the land was needed for the extension of the Woodlands Checkpoint. Before the construction of Woodlands New Town in 1972, this kampong was seemingly isolated from the rest of Singapore as it was sandwiched between the Johor Strait and the forested land. In the past, the villagers worked as fishermen and boatmen, ferrying passengers between Johor and Singapore, but the newer generation started to move out of the kampong to work in the developing Woodlands industrial estate.

Other Malay villages in the northern part of Singapore included Kampung Melayu of Woodlands in the 1950s, Kampung Keranji at Kranji and Sungei Kadut Village. Prone to flooding due to high tides, Kampong Sungei Mandai Kechil was a coastal kampong named after the small stream of Sungei Mandai Kechil. The stream has now converted into an artificial pond at Woodlands Town Garden.

The Chinese villages were the Mandai Tekong Village along Mandai Road, which specialised in large vegetable and orchid farmings in the 1960s, and Sungei Mandai Village near present-day Marsiling estate.

Kampong in Central Parts of Singapore

Upper Serangoon

Built in the 19th century, Yio Chu Kang Road was a major road in the north that runs through the modern-day districts of Upper Thomson, Yio Chu Kang, Ang Mo Kio, Buangkok, Jalan Kayu, Hougang and Serangoon. Various Chinese kampong scattered along the road from Sungei Punggol to Yio Chu Kang Track 14, where the large Yio Chu Kang Village used to exist until the late eighties. The self-sufficient kampong had schools, plantations, goose farms and even a community centre known as Yio Chu Kang Village Community Centre. It also had a popular temple known as Feng Shan Tang (凤山堂).

Chia Keng Village (车宫村) was a Teochew village located at Yio Chu Kang Road, opposite present-day Serangoon Stadium. It was named Chia Keng because of the car repair shops that once plied their trade there. The small village lasted until 1984, making way for the redevelopment of the area.

The main road to Chia Keng was Lim Tua Tow Road, commonly known as ow gang gor kok jio or five milestone of Hougang, and named after Chinese pioneer and Teochew merchant Lim Tua Tow. A popular wet market well-known for its Hokkien mee and chai tow kuay once stood here from the sixties to eighties. When Lim Tua Tow Market was demolished after the mid-eighties, Serangoon New Town has no wet markets and hawker centres other than the ones at Serangoon Gardens. Teck Chye Terrace, a small artery road off Lim Tua Tow Road, is named after Lim Teck Chye, a former secretary of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce.

The community school at Chia Keng Village was known as Sing Hua Public School, founded in 1930 by Chua Cheok San. In its early days, the school campus consisted of only a wooden building, and was occupied by the Japanese as a makeshift barrack during the Second World War. The building became a soap factory after the war but was converted back to a school soon after. The picture shown was the new building of Sing Hua School, opened in 1976. It was, however, torn down in 1984 together with Chia Keng Village, and was relocated to Hougang Avenue 1 as Xinghua Primary School.

There was also a Chia Keng Prison nearby, where its premises was converted from the old army signal camp. The small prison, abled to house only 300 prisoners, was established in 1976, and was used mainly for secret society members and drug offenders. It was demolished in 1993 to make way for the building of HDB flats.

Other Chinese villages near Serangoon were kampong scattered around Lorong Chuan, Lorong Kinchir and Lorong Kudang.

Yio Chu Kang

Kampong Amoy Quee was located at Cactus Road, off Yio Chu Kang Road. It was probably named after Amoy Quee Camp, a former British military camp nearby. The name Amoy Quee was derived from a derogatory term of the Caucasians addressed by the local villagers. In the eighties, Kampong Amoy Quee, along with other Chinese villages along Yio Chu Kang Road, was considerably better off, with some households able to own electrical appliances such as television. The kampong, though, could not escape urbanisation. It was replaced by rows of terrace houses by the late eighties.

Ang Mo Kio

Ang Mo Kio was an undisturbed forested land before the Chinese immigrants settled there at the early 20th century. The new settlers, mostly Hokkiens, cleared the land to set up rubber plantations, and one of the villages established was Cheng San Village. In the fifties, some of the rubber plantations were owned by prominent Chinese businessman and Nanyang University owner Tan Lark Sye (1897 – 1975).

After the rubber boom in the 1920s, the villages switched to vegetable farming and poultry rearing. Cheng San Village was a large kampong by size, made up of mostly Hokkiens and Teochews, and some Malay and Indian families. It stretched from Serangoon Gardens to Upper Thomson Road, and was commonly known as Cheng Sua Lai (青山内). A long track called Cheng San Road used to link Serangoon Gardens to Upper Thomson.

Certain parts of Cheng San Village were inaccessible by vehicles. It was said that during the election periods in the 1960s, small aircrafts were used to drop pamphlets over the kampong and play campaign slogans through loudspeakers. Jing San Primary School was founded in Cheng San Village in 1945 as Chin San School. In 1955, it was shifted to 502 Cheng San Road for the development of the new Serangoon Gardens estate, or Ang Sar Lee (红沙厘), referring to the red zinc roofs of the houses there. Cheng San Village also had an extremely popular temple known as Leng San Giam (龙山岩), reputed for giving out “lucky” numbers for betting.

In 1973, Ang Mo Kio was picked for development as Singapore’s seventh new town. Today, the name Cheng San is used for the area around Ang Mo Kio’s central, reminding us of the large village that used to exist in this region.

Bishan

Since the 19th century, Bishan was a Chinese burial ground called Peck San Theng (pavillion on the green). The Cantonese community was in charge of Peck San Theng, with more than 50,000 graves spread across the region. Kampong San Theng was the main Chinese village then, being established in 1870 by the pioneers from Kwong Fu, Wai Chow Fu and Siew Hing Fu prefectures in Canton, China. Another smaller village Soon Hock Village later became part of Kampong San Theng when the Hokkiens moved in to set up farms and small factories for the production of noodles and sesame oil.

The land of Peck San Theng was acquired by the government in 1973. After exhumation, the area was developed into a new town of what Bishan is today. Peck San Theng, standing next to Raffles Institution, is the only remnant of the demolished Kampong San Theng.

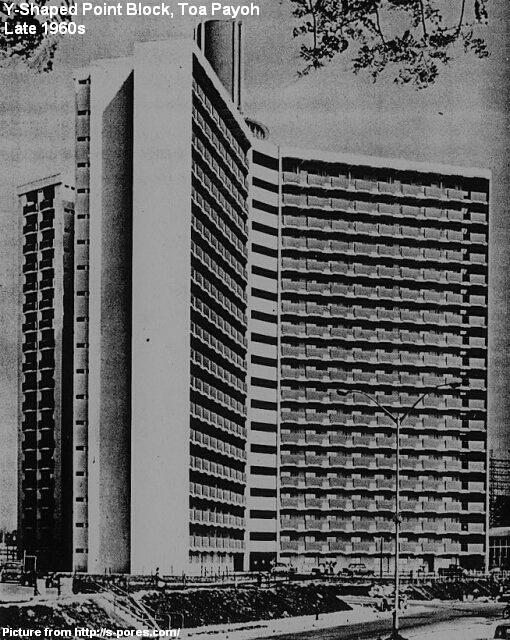

Toa Payoh

Toa Payoh of the past was mainly made up of rural vegetable farms and represented by a Toa Payoh Village. In 1963, the government made a proposal to the villagers, using the new terrace houses at the nearby Kim Keat Road in exchange for their lands and huts. The rapid development saw Toa Payoh became the second satellite town built in Singapore. By 1968, new blocks of HDB flats were standing at the center of Toa Payoh, and a new highway called Jalan Toa Payoh was linked to the new town.

In the seventies, several kampong could still be found located on the outskirts of Toa Payoh, such as the one along Sungei Kallang, at present-day Braddell.

Potong Pasir

The vast vegetable farms at Potong Pasir Village (波东巴西村) were predominated by the Cantonese in the fifties. Coconut, palm and banana trees were also cultivated, while there was also a small cluster of Indian villagers engaged in cattle rearing.

Due to the low lying lands at Potong Pasir, the area was prone to flooding. The villagers would take refuge at the nearby Woodville Hill whenever flooding occurred. One of the worst floods took place in 1978, when hundreds of people were evacuated, massive amount of crops destroyed and thousands of poultry drowned.

Serangoon

A Boyanese-dominated village known as Kampong Kapor once existed near the old racecourse at Farrer Park in the early 20th century. Due to the popularity of horse racing among the Europeans, some of the villagers were employed to look after the race horses.

Kampong in Western Parts of Singapore

Bukit Timah

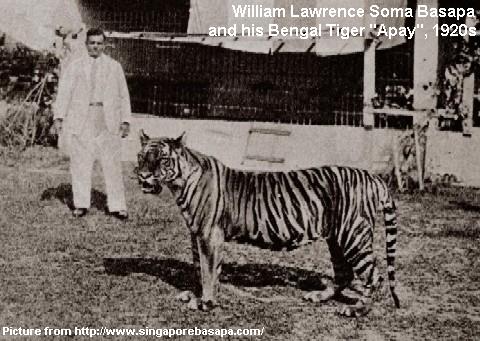

Bukit Timah Village was formed by the early Chinese who settled along Bukit Timah Road near Bukit Timah Hill. One of the earliest roads in Singapore, Bukit Timah Road was built in 1827. In the early 20th century, the villagers lived in constant fear as Bukit Timah was infested by tigers, and it was not until 1930 when the last known wild tiger was captured and killed. The once-densely forested areas at Bukit Timah were also cleared for nutmeg plantations and the establishment of factories such as Ford Assembly Factory and Cold Storage Dairy Farm.

A Malay village called Kampong Chantek existed near the former Turf Club along Bukit Timah Road. It was rumoured that Sir Lawrence Guillemard (1862 – 1951), the Governor of the Straits Settlements from 1920 to 1927, once visited the kampong and praised how beautiful it was. Hence, the humble village became known as Kampong Chantek, where chantek means pretty in Malay. The long Jalan Kampong Chantek and the Pan-Island Expressway’s (PIE) Chantek Flyover are the remnants of the “pretty” village.

Before the late eighties, there was a Lorong Makam located at the end of Old Holland Road off Bukit Timah Road. The road, now defunct, led to a Chinese village known as Hakka Village (客人芭). It consisted of several kampong houses, a primary school and a burial ground. The history of the village went back to 1882, when the early Hakkas from the China counties of Foong Shoon, Eng Teng and Dabu arrived and settled at this area.

Over the past decades, as the residents shifted out of Hakka Village, the primary school was converted into an ancestral temple within Fong Yun Thai Association Columbarium. The surrounding lands had been stayed empty for years until late 2011, when a new condominium is being erected beside the columbarium.

Bukit Merah

Cluster of kampong used to flourish along the former Malayan railway tracks. Two of them were Kampong Silat and Kampong Bahru situated near the now-defunct Royal Malaysian Custom. These villages, along with the ones along the stretch of railways at Jalan Bukit Merah and Upper Bukit Timah, lasted until the mid-eighties. Silat Road and Kampong Bahru Road are the remnants of the Malay kampong that once existed here.

Bukit Panjang

Demolished in 1986, Bukit Panjang Village was a Chinese village that had rows of shophouses and a large Chinese temple worshipping the Taoist goddess (斗母宫). In 1974, Bukit Panjang Village was badly hit by a thunderstorm, affecting thousands of residents and paralysing the traffic.

A Malay village known as Kampong Quarry also existed at the borders of Bukit Pankang. It was located at Hindhede Road, off Upper Bukit Timah Road. In 1947, an Islamic school called Mahadul Irsyad was founded to provide basic Quran and Islamic knowledge to the children. The school later was renamed as Madrasah Al-Irsyad Al-Islamiah.

Choa Chu Kang

Choa Chu Kang was once a kangchu system where gambier and pepper plantations were first set up by the early Teochew settlers along the waters of Sungei Berih and Sungei Peng Siang. The population grew as attap houses were built and forested lands were cleared for more plantations, eventually leading to the emergence of Chinese villages such as Choa Chu Kang Village and Kampong Belimbing, which would include the Hokkiens who arrived later to establish the rubber and pineapple plantations.

Choa Chu Kang Village was located at the Track 10 of Old Choa Chu Kang Road. The track was now defunct and replaced by the new Brickland Road. Other small villages in the district were Kampong Cutforth, which cultivated some sugarcane plantations, Kampong Bereh and its fish farms, coastal village Kampong Jurong Tanjung Balai, Kampong Sungei Tengah, Tong Seng Village (东成村) and Lam San Village (南山村).

In the late eighties, many of these kampong were demolished for the development of Choa Chu Kang New Town. By 1992, rows of new colourful high-rise HDB flats had replaced most of the attap houses.

Yew Tee Village was also a small quiet Chinese kampong located near Stagmont Ring, off Woodlands Road. Yew Tee refers to “oil pond” in Teochew, taking reference from the nearby oil storage facilities during the Japanese Occupation. Engaging in vegetable farming and poultry rearing, the strength of the village declined over the decades from more than 300 families to less than 20 households in 1991. By early nineties, most residents had left for the new housing estates of Choa Chu Kang and Jurong East.

Lim Chu Kang

Lim Chu Kang Village was another kangchu system located along the river banks of Sungei Kranji. It was headed by a Lim clan, but the founder was Neo Tiew (1883 – 1975), who made massive contributions to the development of this region, such as education, healthcare, social security and power supply. Neo Tiew Road and Neo Tiew Estate are named after him.

In the early days, like other kangchu systems in Singapore, the villagers in Lim Chu Kang specialised in gambier and pepper planting. Rubber plantations were later set up, with investment by the wealthy Irish Cashin family. In 1979, along with Punggol, Lim Chu Kang was one of the two designated districts in Singapore for pig rearing, after the government passed the law to prohibit pig farms in other parts of the island.

Neo Tiew Village (梁宙村), Thong Hoe Village and Ama Keng Village were smaller Chinese villages located in other parts of Lim Chu Kang, which had vast vegetable and chicken farms. The villagers still largely retained their frugal life by the mid-eighties, where some families used firewood for cooking. Thong Hoe Village was situated near Sungei Gedong Road, while Ama Keng Village sat beside Tengah Air Base. It had one of the oldest Chinese temples in Singapore, called Ama Keng (grandmother palace) Temple, which was built in 1900 to worship the goddess of peace and happiness. There were also various community centres at Neo Tiew, Thong Hoe and Ama Keng to serve the people.

Jurong

Jurong remained largely a rural area until its development after Singapore’s independence. The public housing plan kicked off only in the eighties, much later as compared to other estates elsewhere in Singapore. Hong Kah Village (丰加村) was one of the kampong in Jurong, with its fruit tree plantations and fish farms, that survived until the late eighties. Part of Hong Kah Village evolved to become a restricted area of Tengah today, bounded by Pan-Island Expressway (PIE) and Kranji Expressway (KJE), and its residents moved to the nearby neighbourhoods.

In the 1950s, the major stream of Jurong River (or Sungei Bajau Kanan) was home to many Malay fishing villages, such as Kampong Jawa Teban (or Kampong Java Teban). The fishermen’s wooden houses were built on stilts that stretched out into the waters, with fishing boats parked by the sides. It was a common to see the children having an enjoyable time swimming in the river, while the adults laboured in fish netting and prawn rearing. The fishing villages located nearer to the mouth of Jurong River, however, were constantly bothered by the flooding due to high tides.

Tuas

A swampy land in its early days, Tuas was inhabited by the Malay population as a fishing village. Tuas Village was located nearer to West Coast Road rather than present-day Tuas South, which was the result of land reclamation during the eighties. The southwestern part of Singapore had long been designated for industrial use, thus Jurong Town Corporation (JTC) was acquiring the lands since 1974 for their marine and engineering industries.

By the end of the eighties, most residents of Tuas Village had moved to the public housing estates, and the remainders of Tuas were small clusters of kopitiams, shophouses and four seafood restaurants near the coasts. Like the one at Punggol end, the seafood restaurants enjoyed brisk businesses and good reputations, until they were phased out after 1986.

Kampong in Eastern Parts of Singapore

Paya Lebar

Paya Lebar’s Kampong Yew Keng (葱茅园村) near Lorong Tai Seng was famous for a Chinese temple known as Nine Emperor Gods (九皇宫). The year 1965 was significant to Lorong Tai Seng as new rows of shophouses were built and new street lamps were installed along the road. The road no longer exists today.

Katong

In the 1920s, clusters of attap houses made of wood, nipah palm, rumbia and bertam forming Tanjong Katong Village could be found at the lands south of Geylang. Before the land reclamation of East Coast in the sixties, the coastline was within reach of the Chinese village.

Bedok

In the 1920s, a Chinese village was formed on the lands around the now-defunct roads of Peng Ann and Peng Ghee, off Upper Changi Road. It was Kampong Chai Chee, a large village of attap houses with vegetable farms flanked with rows of coconut and banana trees, and had its bustling market which gave the village its name Chai Chee (菜市), literally refers as “vegetable market”. The market sold, other than vegetable, pork, poultry, fish, fruits and eggs.

In the seventies, the residents of Kampong Chai Chee were resettled as the area was developed to for the building of HDB flats and the Bedok Reservoir. By early 1980s, Chai Chee became a fully urbanised housing estate, the first such estate in the eastern part of Singapore. Today, Chai Chee is part of Bedok New Town.

Other kampong in present-day Bedok included Ulu Bedok Village, just opposite Kampong Chai Chee across Peng Ann Road, Bedok Village, Simpang Bedok Village and Sompah Bedok Village, famous for its cattle farms. The last of these villages were gone by 1986.

Kallang

The Kallang Basin had been home to many settlements since the early 19th century. Orang kallang was one of the first settlers at the river, leading a nomadic life before they were unfortunately wiped out due to a smallpox outbreak. The early Malay dwellers later formed a coastal fishing village known as Kampong Kallang, which thrived in the early 1900s.

Kampong Rokok was a Malay village off Geylang Road near the Kallang Bridge.

Geylang/Ubi/Eunos

One of the oldest Malay settlements in Singapore, Geylang Serai also functioned as a main trading place for the Malays from Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei. In the late 19th century, the rich Arabs moved in to cultivate lemon grass plantation but the industry failed to boom, which was later replaced by rubber plantations and vegetable farms. The villagers also started planting tapioca (ubi in Malay) during the Second World War, leading to the naming of Kampong Ubi, part of Geylang Serai.

Kampong Melayu was a large self-sufficient Malay village that stretched from the borders of Geylang to Jalan Eunos, where a smaller kampong called Jalan Eunos Village stood. There was a couple of Chinese families living in Kampong Melayu. In the racial riots of 1964, the village was one of the worst hit areas. A huge fire broke out at Kampong Melayu in 1975, destroying several houses and leaving dozens of people homeless.

Kampong Melayu’s main religious center was the old Alkaff Mosque. It was demolished in 1980 and a new one was built near Bedok Reservoir Road. By 1985, Kampong Melayu had to be torn down for the development of the industrial estates at Eunos.

Kembangan

Kampong Kembangan and Kampong Pachitan co-existed until the mid-eighties in today’s Kembangan district. The name Kembangan means “expansion” in Malay, and it was a predominantly Malay village, with several Chinese families living in it. The educational and social needs were provided by a Sin Sheng School and the Kampong Kembangan Community Centre.

The villages’ main road Jalan Kembangan was named as early as 1932 and gradually lost its importance after the eighties, replaced by Sim Avenue East and Changi Road.

Pasir Ris

Pasir Ris was once a low-lying swampy ground with a popular beach for outings and picnics from the fifties to seventies. Several Malay villages such as Kampong Pasir Ris and Kampong Bahru used to coexist with the large timber plantations near Elias Road. Elias Road was an old road in Pasir Ris, named after the wealthy Elias family, where they had a bungalow at the end of Elias Road. Justice of Peace and Municipal Commissioner of Singapore Joseph Aaron Elias was a prominent Jewish businessman in the early 20th century.

By the sixties, the various plantations ceased to exist after the timber industry declined. Meanwhile, pig farms flourished at Loyang during the seventies.

Tampines

Tampines Village was originally situated near Sungei Serangoon at the 7th milestone of Upper Serangoon Road (Lim Tua Tow Road is 5th milestone, while Simon Road is 6th milestone). Tampines New Town is located 5km east of where Tampines Village was, and instead was the land where Kampong Teban, Teck Hock Village, Kampong Beremban and Kampong Sungei Blukar once stood on. By the mid-eighties, rows of flats were erected at Tampines. The likes of Teck Hock Village were torn down but some tropical fish farms still survive till this day at Fish Farm Road.

In the past, Tampines was covered with kampong, farms, temples, forests and sand quarries. Old Tampines Road, one of the oldest roads in Singapore, was built in 1864, linking Upper Serangoon Road to Upper Changi Road. The villagers would make use of the dusty path to travel to Hougang and Serangoon.

Changi

The Changi Village at the most eastern part of Singapore saw tremendous changes over the decades. The kampong was still made up of attap houses in the fifties and sixties. By the early seventies, the village has prospered into a little town with many concrete shophouses thanks to the presence of the British military personnel. Changi was the last area in Singapore to be pulled out by the British upon their official withdrawal in 1971, after which the government launched the Changi Village Development Project, adding low-rise flats and a park to the little estate.

Another bustling village stood at the 10th milestone of Upper Changi Road. It was the Somapah Village (or Somapah Changi Village). Lasted until the eighties, the village was progressing well, equipped with public schools, clinics, temples, an open-air theatre, barber shops as well as cattle and goat farms. Somapah Village was later razed to the ground to make way for the Changi Business Park.

In 1975, Singapore launched one of its biggest project in history: Changi Airport. Massive land reclamations were carried out and the rivers of Sungei Tanah Merah Besar, Sungei Ayer Gemuroh and Sungei Mata Ikan were drained and diverted. Hundreds of buildings and thousands of graves in the region were demolished and exhumed. The fishing villages by the rivers, such as Kampong Mata Ikan, were also unable to escape the fate of urbanisation.

Kampong in Southern Parts of Singapore

Queenstown

Before the development of Queenstown by the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) in 1954, the area was made up of a large Hokkien village largely known as Boh Beh Kang (No Tail River). Its name derived from the stream that flowed between two hills called Hong Yin Sua and Hong Lim Sua, linking the Singapore River and the West Coast. The river had been converted into a canal today.

Villagers from Boh Beh Kang had their ancestry traced to Tong’An, Fujian of China. Most of them were from the extended Ang family.

Pasir Panjang

Pasir Panjang used to be a stretch of sandy beach along the southern coast of Singapore, where bungalows and resorts owned by the wealthy businessmen were abundant. In the 1930s, some Malays from Sungei Kallang settled at Pasir Panjang when Kallang Airport was being constructed. The coastal fishing settlement became known as the West Coast Malay Settlement, but it would only last until the sixties when Pasir Panjang was acquired for land reclamations and the building of a new port terminal.

Telok Blangah

Telok Blangah Hill was home to several early villages such as Kampong Bahru, which was resettled by the people of Temenggong Abdul Rahman after he signed the treaty with Sir Stamford Raffles and the East India Company to allow the British in setting up a trading post in Singapore.

Kampong Heap Guan San was a Chinese village later established at Telok Blangah. It was troubled by a series of crimes in the sixties, such as possession of revolver and opium. The Malayan Paints Work once operated its factory here. Another village at Telok Blangah was Kampong Jagoh. Its primary school known as Kampong Jagoh Malay School was opened in 1949, which became Jagoh Primary School in the eighties (now defunct).

Situated at the foot of Telok Blangah Hill, Kampong Radin Mas was well-known as a royal village in the fifties. This was due to the legend of Javanese princess Radin Mas Ayu, who escaped to Singapore from the Sultan of Java, her uncle, and settled at Telok Blangah.

Another Malay village was Kampong Berlayer near the current Labrador Park.

Tanjong Pagar

Kampong Samau was located at Palmer Road, off Shenton Way, in the fifties. Palmer Road was a result of the leveling of Mount Palmer in the early 20th century, named after Indian merchant John Palmer (1766 – 1836). The Malay village was known for its religious place-of-worship Habib Noh Shrine, which was built in 1860s. The shrine is now housed by the mosque of Masjid Haji Muhammad Salleh.

Another Malay village called Kampong Batek was demolished under force in 1947 due to the redevelopment plans. There were about 20 to 30 families in the kampong when the bulldozers were sent in, prompting outcry from the public.

Bugis/Rochor

Bugis was named after the Buginese, a seafaring tribe originated from the South Sulawesi of Indonesia. Even before the arrival of the British, the Buginese was already active in the trading with the locals around the Singapore River and Kallang Basin. By the late 19th century, a coastal Malay village called Kampong Buggis (spelt with double G) was formed on the left side of Kallang Basin.

Other villages nearby were Kampong Java Road, Kampong Saigon, Kampong Kapur (or Kapor), Kampong Boyan and Kampong Bencoolen, scattered in a region between Sungei Rochor and the Singapore River.

Kampong on the Islands of Singapore

Pulau Tekong

Pulau Tekong was home to many Malay residents before the island was developed as a military base in the eighties. In 1956, the population living on Pulau Tekong was about 4,000 strong, scattered in various small kampong such as Kampong Pahang, Kampong Selabin (Pekan), Kampong Seminal, Kampong Batu Koyok, Kampong Pasir, Kampong Sungei Belang, Kampong Onom, Kampong Pasir Merah, and Kampong Permatang. The villages were self-reliant on vegetable, fish, coconuts and tropical fruits.

There was also a small Chinese community, mostly Hakkas and Teochews, living at Kampong Sanyongkong (or Kampong Senyunkong) located near the south of the island. Starting from 1986, all the islanders were gradually resettled on mainland Singapore. Sanyongkong Field Camp, built in 2006 for the Combat Engineers, was named after this extinct kampong.

Pulau Ubin

The only rustic village atmosphere one can find in an urbanised Singapore, other than Kampong Lorong Buangkok, is Pulau Ubin. Some Malay kampong such as Kampong Leman, Kampong Cik Jawa, Kampong Melayu, Kampong Bahru, Kampong Noordin and Kampong Jelutong once stood on this northeastern island that stays largely undeveloped for decades. There is a folktale that a Sungei Kallang dweller named Encik Endun Senin led his people to migrate to Pulau Ubin in the 1880s.

Pulau Ubin was well-known for its granite quarries as early as the 19th century. The granite produced was used in several projects such as Pedro Branca’s Horsburgh Lighthouse, the Woodlands Causeway and some HDB Flats. The Chinese quarry workers arrived on the island in the 20th century, with some of them settled down and made the island their homes. The Chinese village, still surviving till this day, is located near to the jetty.

Sentosa (Pulau Blakang Mati)

In the late 19th century, Pulau Blakang Mati was inhabited by the orang laut at Kampong Kopit. Viewed as a strategic location for defense, the British built a series of fortifications such as Fort Siloso, Fort Serapong and Fort Connaught from 1880 to 1935. The island was captured and used as a prisoner-of-war camp by the Japanese during the Second World War.

Before the development of the island in the seventies, several Malay kampong existed on Pulau Blakang Mati. There was a Blakang Mati Primary School (renamed as Sentosa Primary School after the island was renamed as Sentosa in 1970) to provide education for the children of the islanders. It was established in 1964 but demolished ten years later to make way for the Maritime Museum.

A Chinese village known as Yeo Village (杨家村) also once existed on Pulau Blakang Mati.

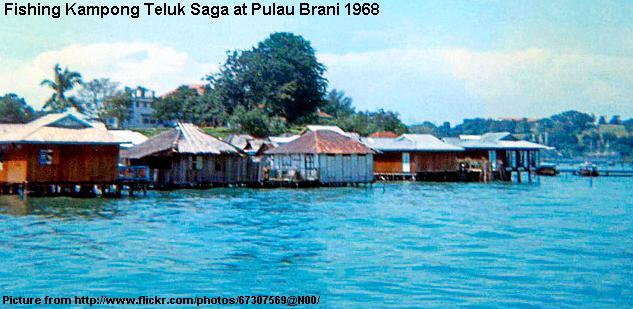

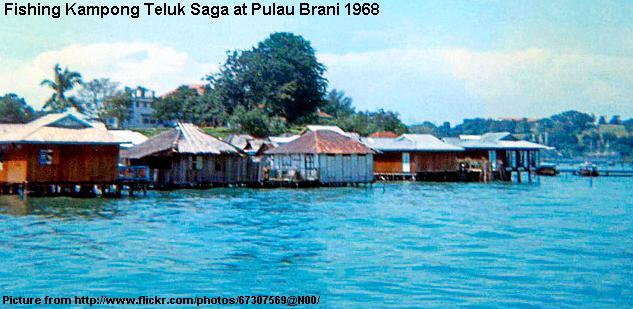

Pulau Brani

A Malay fishing village called Kampong Teluk Saga once existed on the northern side of Pulau Brani. Rows of wooden houses owned by the fishermen lined up on stilts along the coastline.

By 1971, a naval base was built on the island, facilities were added such as Pulau Brani Community Centre and two primary schools called Tai Chong and Teluk Saga. The villagers were gradually resettled onto mainland Singapore. Today, the island is functioning as Brani Container Teminal, and is restricted to public access.

Other Islands

The outer islands opposite Pasir Panjang such as Pulau Bukom, Pulau Busing, Pulau Hantu, Pulau Semakau and Pulau Sebarok were inhabited by several Malay fishing kampong, before the islands were converted for industrial use.

Pulau Bukom has been Far East’s main oil supply centre since 1902, and was the site of Singapore’s first oil refinery in 1961, built by oil and gas giant Shell. Like Pulau Brani, the islands are now restricted from access by the public.

Pulau Semakau was acquired by the Singapore government in 1987, and the villagers were mostly resettled at Telok Blangah and Bukit Merah. The last resident held his place until 1991. The island was later linked to the nearby Pulay Sakeng to became Singapore’s first offshore landfill.

Editor’s Note: The editor has lived in a HDB flat all his life, but has fond memories of his mother’s kampong at Chia Keng village in the early eighties.

Read the history of Singapore’s public housing in From Villages to Flats (Part 2) – Public Housing in Singapore, and shophouses in From Villages to Flats (Part 3) – Traditional Shophouses.

Published: 04 April 2012

Updated: 15 May 2016

Major in Physics at Nanyang University, Chia Thye Poh became a teacher and an assistant lecturer before joining Barisan Sosialis to participate in politics. In 1963, Barisan Sosailis contested in its first general election, winning 13 seats compared to the People’s Action Party’s (PAP) 37. Chia Thye Poh was successfully elected as a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Jurong constituency.

Major in Physics at Nanyang University, Chia Thye Poh became a teacher and an assistant lecturer before joining Barisan Sosialis to participate in politics. In 1963, Barisan Sosailis contested in its first general election, winning 13 seats compared to the People’s Action Party’s (PAP) 37. Chia Thye Poh was successfully elected as a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Jurong constituency.

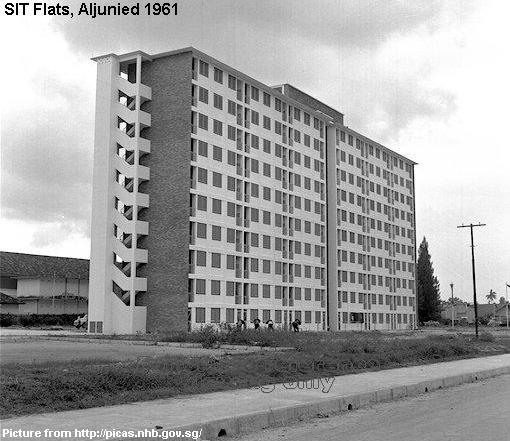

In its first decade of operation, HDB raised the percentage of Singapore’s population living in public housing from 9% to 32%, supplying more than 100,000 units. The early projects in HDB’s second five-year plan (1960-1965) covered Telok Blangah, Rochor, Henderson, Outram, MacPherson, Serangoon and the Kallang Basin. The United Nations (UN) experts were invited to advice on the country’s urban renewal plan, which was targeted to accommodate a population of 4 million people. After Queenstown which was partially a SIT project, Toa Payoh became the first new town to be fully completed by HDB in 1968.

In its first decade of operation, HDB raised the percentage of Singapore’s population living in public housing from 9% to 32%, supplying more than 100,000 units. The early projects in HDB’s second five-year plan (1960-1965) covered Telok Blangah, Rochor, Henderson, Outram, MacPherson, Serangoon and the Kallang Basin. The United Nations (UN) experts were invited to advice on the country’s urban renewal plan, which was targeted to accommodate a population of 4 million people. After Queenstown which was partially a SIT project, Toa Payoh became the first new town to be fully completed by HDB in 1968. The efficiency of HDB was led by Lim Kim San (1916-2006), HDB’s first chairman (1960-1963) and Singapore’s Minister for National Development (1963-1965), who was credited for his massive contribution to the public housing. The role to lead HDB as the new public housing provider was deemed a difficult one, but Lim Kim San volunteered for the position and did not get paid for his three years at HDB.

The efficiency of HDB was led by Lim Kim San (1916-2006), HDB’s first chairman (1960-1963) and Singapore’s Minister for National Development (1963-1965), who was credited for his massive contribution to the public housing. The role to lead HDB as the new public housing provider was deemed a difficult one, but Lim Kim San volunteered for the position and did not get paid for his three years at HDB.

The ruling party PAP (People’s Action Party) enjoyed high support from the people from the sixties to the eighties. One of the factors was the success of HDB and their five-year plans, which provided continuous supply of low-cost affordable flats for the masses. Low-middle income families were able to rent, and later purchase, housing units at reasonable rates. The transition from living in kampong to flats had great impact to many people, as they could enjoy the convenience of having water, electricity and gas supplies at their finger tips. Young generations of that era were also encouraged to get married, have homes and start their own families.

The ruling party PAP (People’s Action Party) enjoyed high support from the people from the sixties to the eighties. One of the factors was the success of HDB and their five-year plans, which provided continuous supply of low-cost affordable flats for the masses. Low-middle income families were able to rent, and later purchase, housing units at reasonable rates. The transition from living in kampong to flats had great impact to many people, as they could enjoy the convenience of having water, electricity and gas supplies at their finger tips. Young generations of that era were also encouraged to get married, have homes and start their own families. HDB also introduced the Design, Build and Sell Scheme (DBSS) in 2005. Pinnacle@Duxton was a success, with its excellent location and award-winning design. However, the prices of DBSS flats kept climbing. By the time Centrale 8 was launched in 2011 at Tampines, the eighth DBSS project, its asking price for a five-room unit was as high as $880,000. This caused a huge uproar from the public, and subsequently prompted the government to stop land sales for future DBSS projects. The Pasir Ris One of 2012 is expected to be the last DBSS flat to be built.

HDB also introduced the Design, Build and Sell Scheme (DBSS) in 2005. Pinnacle@Duxton was a success, with its excellent location and award-winning design. However, the prices of DBSS flats kept climbing. By the time Centrale 8 was launched in 2011 at Tampines, the eighth DBSS project, its asking price for a five-room unit was as high as $880,000. This caused a huge uproar from the public, and subsequently prompted the government to stop land sales for future DBSS projects. The Pasir Ris One of 2012 is expected to be the last DBSS flat to be built.