With the completion of the Integrated Resorts (IRs) and its casinos in 2010, some said that Singapore had truly become a sin city. While they might be right, the fact is gambling has never been a stranger on this island.

This article, however, has no intention in justifying gambling and betting.

The Colonial Days

In the 19th century, the early Chinese immigrants in Malaya and Singapore, many working as coolies, were plagued by the addiction of gambling and opium. Much of their hard-earned money was spent on these vices, resulting in a number of them unable to return to China and die penniless in Nanyang. Under his charge, Sir Stamford Raffles (1781-1826) outlawed cock-fighting, popular among the Malays, and the Chinese gambling dens.

When Raffles left Singapore for Bencoolen in 1820, he left the colony under the care of Scottish William Farquhar (1774-1839). Farquhar viewed gambling as a source of income for the colonial government, and subsequently issued licenses to the big Chinese operators of gambling dens.

Throughout the 19th century, the policy of legalising gambling was changed repeatedly. Despite the laws, gambling dens continued to exist and flourish until the mid of the 20th century. The China Street in the present-day Central Business District (CBD) was once known as giao keng kau 赌间口, due to the numerous gambling dens operating there in the old days. The notorious street was also dominated by powerful secret societies and moneylenders.

Singapore Turf Club and Horse Racing

Scottish businessman Henry Macleod Read (1819–1907) founded the Singapore Sporting Club in 1842 and had Singapore’s first ever horse racing held at Farrer Park a year later, with the top prize money offered at $150.

In 1924, the club changed its name to Singapore Turf Club and its premise was shifted to a larger ground at Bukit Timah in 1933 (and to Kranji racecourse in 1999). Ever since 1960 when horse racing was officially opened to the public, the sport-betting was so overwhelming that the two grandstands with capacity of 50,000 were easily filled up during the weekends.

Second World War

During the Japanese Occupation, all sorts of gambling were unofficially allowed. The Japanese even introduced a lottery called Konan Saiken, Singapore’s first ever state lottery, in 1942 to raise revenue for their administration. With the top prize of $50,000, each ticket cost $1 and all civil employees were required to buy.

During the Japanese Occupation, all sorts of gambling were unofficially allowed. The Japanese even introduced a lottery called Konan Saiken, Singapore’s first ever state lottery, in 1942 to raise revenue for their administration. With the top prize of $50,000, each ticket cost $1 and all civil employees were required to buy.

Post-War Period

After the war, the British returned as Singapore struggled to recover. There were more interactions between the white rulers and the people, although the social divide was still very much in place.

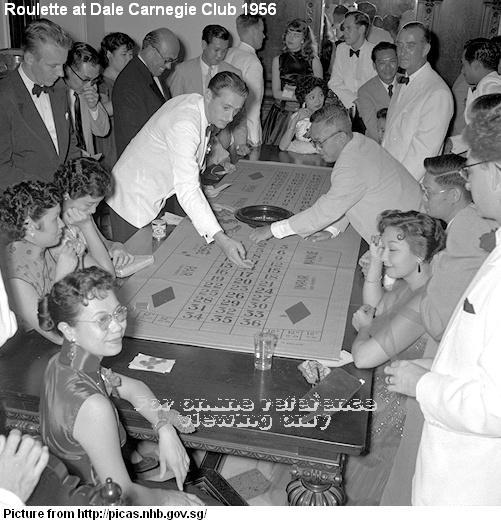

Roulette and other card games had always been the favourite pastimes of the upper class in the colonial Singapore. The picture shows a mixture of British and local patrons playing at a roulette table in the Dale Carnegie Club (a club formed by a group of Singaporeans who graduated from the speech-training course of the same namesake) in 1956.

Independence and The Singapore Pools

The society of Singapore, after independence, was overrun by the underworld trials, which had a hand in almost all illegal activities such as gambling, drugs and prostitution. In order to tackle the issue of illegal gambling, the Singapore Pools Private Limited was set up on 23rd May 1968 as the sole legal operator of lottery. Its temporary office was opened at Mountbatten Road.

Toto

Two weeks later, Singapore Pools launched the lottery of Toto as its first game, with the help of Bulgarian Toto expert Papadopov Nikolai. The public response was so overwhelming that the limited Toto coupons were snapped up within the first few hours of sale at the Singapore Post Office.

The Singapore Sweep

One year later in 1969, the Singapore Pools continued its successful start with the introduction of The Singapore Sweep. The first prize was set at $400,000, an astronomical figure during that era, and tickets costing $1 each were sold at small booths in many parts of the island. The prize would be raised to $1 million by 1983.

4D

On 26th May 1986, Singapore Pools launched the computerised 4-digit number game simply known as 4D (摇珠万字票), arguably the most popular betting game in Singapore. It is reported that more than 50% of Singaporeans has participated in the purchase of 4D in one way or another. The 4D draw days were initially held only on the weekends, but were extended to Wednesday after 2000.

Said to be originated from Kedah in 1951, 4D has been extremely popular in both Singapore and Malaysia. It is commonly known as beh bio (马票, literally means “horse ticket”), although it is actually a machine that randomly draw out four balls, each representing a single digit. However, in the sixties, 4D was drawn in the Singapore Turf Club. The game was influenced by Hong Kong horse racing, where each set of numbers was randomly picked and then assigned to a horse. The first, second and third prizes were determined by the winning horses in the race. Starter prizes and consolation prizes are commonly known as ji wei (入围, qualification) and beh sai (马屎, literally means horse shit) respectively.

Many locals like to get inspirations of numbers from newspapers, deities, or even car accidents and Luohan fish. Sometimes, they also roll up red slips of papers, each with a digit (zero to nine) written underneath, in a small milk can and shake out four digits to form a set of lucky number. Most folks lose in the long run, but that does not stop their dreams of striking the big prizes. In 2005, a middle-aged man struck $14 million, the biggest win in the history of Singapore 4D.

Once in a while, one can also read from newspapers that a certain ang zi (红字) comes up as first prize and causes some illegal underground bookies to bust. On the contrary, unlucky numbers are called orh zi (黑字). Someone has researched that as many as 20 numbers have never “opened” in the history of 4D.

Football Betting and Others

Other than significant contributions to the building of the National Stadium and The Esplanade, Singapore Pools also showed its support to the development of local football when S-League started in 1996.

It launched SCORE in 1999, and later STRIKE! in 2002, as a channel of legalised betting in local and international footballs. The move also aimed to stamp out illegal football betting, which was starting to become very popular among Singaporeans since the late nineties.

By the 2000s, Singapore Pools had expanded in many sectors, including a scratch-and-win game called Scratchit!, system roll and iBet in 4D, telephone betting through PoolzConnect and betting in Formula One racing. Today, there are more than 280 Singapore Pools outlets in almost every corners of Singapore.

By the 2000s, Singapore Pools had expanded in many sectors, including a scratch-and-win game called Scratchit!, system roll and iBet in 4D, telephone betting through PoolzConnect and betting in Formula One racing. Today, there are more than 280 Singapore Pools outlets in almost every corners of Singapore.

Illegal Mobile Gambling Stalls

For decades, illegal gambling dens and stalls in Singapore have never been totally eradicated. The small stalls have high mobility, been able to be set up and packed up in double quick time. It is not surprising that they can still be found in the back alleys of Geylang today.

Jackpot Rooms

Before the opening of IRs, jackpots and fruit machines have already found their way into Singapore. Social clubs such as NTUC (National Trades Union Congress) Club, Automobile Association of Singapore (AAS) and SAFRA (Singapore Armed Forces Reservist Association) have brought the game machines in since the nineties.

Although they are restricted to members above the age of 18, the public raises their concerns when some of the clubs located in the residential neighbourhoods are found operating these machines. In 2007, jackpot machines around Singapore raked in as much as $700 million worth of revenue.

Trips to Genting Highlands and Casino Ships

Tens of thousands of Singaporeans travel some 400km to Genting Highlands, Malaysia every year. In the eighties, before the North-South Highway was fully completed, many determined Singaporeans would drive 10 hours in poorly lit single-lane roads flanked by vast plantations in Malaysia to get to their destinations.

Casino ships were once popular with the local gamblers too. Rebates of betting chips and free buffets have lured many to visit Leisure World at the international waters off Batam. In the past, there were whispers that many local housewives visited the casino ships daily; they would board the ships in the mornings and return by the evenings, to avoid suspicions from their husbands. A lot of them lost their savings by tens of thousands of dollars.

Types of Popular Games in Singapore

Chap Ji Kee

Gambling in public was banned in Singapore until the sixties. One local lottery chap ji kee (十二支), though, was extremely popular then, especially among the housewives. They would use some of their monthly allowances or savings to bet, hoping to strike the first prize.

The game was simple, as one just needed to choose two numbers from one to twelve, and place them in either horizontal or vertical arrangement. In the vertical arrangement, the sequel of the two numbers must be correct in order to win the payout, often to more than 10 times the size of each bet. Codes were used on the betting slips, usually by circles and lines to indicate the stake amounts.

Runners would then collect the slips usually at the kopitiams, and bring them to a centralised location where the numbers would be drawn and announced.

Si Sek Pai

Si sek pai (四色牌), literally “four colour cards”, is a favourite Teochew card game popular among housewives. As the name suggests, the 112 cards are divided into four colours (yellow, red, white, green), 28 cards each. In each colour, the cards are listed as General (将), Guard (仕), Advisor (相), Chariot (車), Horse (马), Cannon (炮), and Pawn (卒), much like the Chinese chess.

La Bi

La bi is a corrupted pronunciation of rummy, a card game similar to si sek pai. It uses normal playing cards which involve drawing of cards, making melds and discarding the unwanted cards on hand. While si sek pai is mostly played by housewives, la bi seems to be a favourite game of local middle-aged men in the eighties and nineties.

Singapore Mahjong

Mahjong is one of the favourite pastimes here. A few rounds of mahjong at home are not considered illegal in the eyes of Singapore law, unless there are syndicates involved with the intention of profiting.

Singapore mahjong is unique in its own way, with its set of rules and regulation (eg. animals are involved as tai 台, game ends at last 15 tiles, stakes are increased geometrically, etc). Below is a brief comparison with the main characteristics of other variants of mahjong in the world:

- Hong Kong (Cantonese) Mahjong: No animals; game ends until last tile

- Japanese (Richi) Mahjong: The player must declare when he is “listening” for the winning tile, known as tenpai (听牌)

- Taiwan Mahjong: 16-tiled play; more variety in tai without limit in stakes

- American Mahjong: Interchangable of tiles among players at the start of each game

- KL (Kuala Lumpur) Mahjong: Usually 3 players, with jokers involved

- Sichuan Mahjong: Chi (吃) is disallowed; flowers, animals, wind (东南西北风) and dragon (发财红中白板) tiles are all excluded

- Korean Mahjong: 3 players with only wan zi (萬子) and tong zi (筒子) played. There are no suo zi (索子)

- Vietnam Mahjong: Includes 16 jokers (Kings, Queens, others) which act as replacement of tiles or increment of tai

Overall, the style of Singapore mahjong most resembles that of Hong Kong mahjong. Even the taboos of the superstitious gamblers are similar, such as tapping of shoulders are prohibited, school bags and combs are considered unlucky items (they sound like losing in Mandarin), discarding of west wind at the start of a game is also considered unlucky as west is xi (西) in Chinese, hence referring to xi tian (西天).

However unlike Hong Kong, mahjong is also seldom played in weddings and funerals. The Singapore government also does not allow the operation of mahjong parlours.

Others

Other card games such as Blackjack, Cho Dai-D, Pusoy (Chinese Poker) and Texas Poker are also commonly played in Singapore. Mahjong and blackjack are especially popular among friends and relatives during Chinese New Years.

Published: 30 November 2011

Updated: 28 September 2015

Those are the gambling experience of the adults.But we children have our version of legalised gambling from the mama shops.

a) Tikam tikam- A series of folded papers pasted on a board .You choose one and look for the number pasted inside. Cash prizes for lucky numbers range from 10 cents to a dollar. Housewives earned some pocket money by helping to paste these printed numbers on the card board given. They can arrange the papers in any arrangement and they know that the chance of winning a big prize is slim.Anyone has a photo of the tikam tikam of the 1960s?

b)Chewing Gum Lucky Draw. Children pay 5 cents and stand a chance to win packs chewing gum packs that come in various sizes and assortment. The lucky winner is the one who got the biggest pack with his 5 cents. Anyone has a photo of the chewing gum lucky draw? Would love to share this with my children.

as at today.. only 1 number didnt ‘open’ before in 4D history … 0350 , just go singaporepools website and you can find it~

0350 has opened before in 2013/2014 and 2017.

It brings back memories of my maternal grandma.

She would ask me to go to this provision shop and to the back and read the results of the draw of the 十二支 from the “calender”.

I would shout out: “Ah ma! Two seven small!”

Then the provision owner would complain to my grandma… Oh! I am supposed to whisper softly to her… LOL!

I feel that arcades are kinda like gambling for kids. Many games give out tickets and these can be exchanged for various prizes at the counter. I have also seen jackpot machines in arcades…

nope u haven’t

I lost all my saving by playing 4-D it is a devil game you dont play the numbers comes out you play on sat and not on sunday the numbers appeared. I only won last month when I was in Singapore the number is 5573 consulation I put $25.00 and paid $1500. and lost $300.00 but one in the casino $360.00

Those Four Colour Cards(四色牌/Si Sek Pai) can still be found in Singapore. Hua Goi Company Pte Ltd manufactures them. Feel free to visit Hua Goi’s Website at http://huagoi.wordpress.com/ for more information on Four Colour Cards. You can also drop us an email at huagoi@hotmail.com if you have any other enquiries. Thank you.

In 1949. I was a member of the Volunteer Special Constabulary (VSC) attached to Beach Road. Among other things, we also carried out raids on illegal gambling in some of the Lorongs in Geylang. Of course, we were all armed, the constables with revolvers, and the NCO with a Sten. It was rough in those days. What a life !

Four ladies having a game of mahjong at their Chinatown home.

The year was 1956; curfew hours were being enforced during the Chinese Middle School Riots

(Source: National Archives of Singapore)

this does not even help me in my history exam except for 1 paragraph.

lol

Desperate housewives and the lure of chap ji kee

29 November 2015

The Straits Times

In 1977, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, explaining the need for state-run lotteries such as Big Sweep and Toto, said: “If you do not run (the lotteries), the chap ji kee man who has always swindled the people of their money is still there. It is the history of Singapore. The Chinese who travelled overseas are the biggest gamblers you can find in the world. Because to leave China was to gamble. In Manchu China if you returned you were beheaded. Because you were bringing in dangerous foreign ideas. So to leave China for Nanyang was a gamble.”

Mr Lee’s words point to the perennial thorny question on the control of a vice that is intertwined with the early beginnings and social history of the Chinese community in Singapore. While the allure of chap ji kee has faded, it had, for more than half a century, been the most entrenched and widespread form of illegal public gambling in Singapore.

THE ROOT OF ALL EVIL

In 1823, following his return from a four-year administrative stint in Java, Stamford Raffles, the founder of modern Singapore, issued orders for the suppression of gambling in the colony. Severe penalties were introduced such that “whoever games for money or goods shall receive 80 blows with a cudgel on the breech, and all money or property staked shall be forfeited to Government”. This was a move to remedy what Raffles perceived as the moral laxity of the administration under the first resident, William Farquhar, who had set up gambling, opium and spirit farms against Raffles’ wishes, where revenue from the sale of gambling licences was used for public works.

According to the memoirs of Abdullah Abdul Kadir, a teacher of the Malay language, the Chinese – for whom gambling was a major pastime – “sighed and drew deep breaths (with) a grim look on their faces as they grumbled and abused Mr Raffles for preventing them from gambling”. Abdullah, who not only worked for Raffles as a scribe and interpreter but was also an admirer of the man, castigated the naysayers for failing to recognise that the measures were for their own good. The temptation of quick money often led to debt and crime. In his defence of Raffles, Abdullah declared: “(It) is obvious that gambling ruins people, deceives them and puts wicked ideas into their minds. Gambling is the mother of vice, and of her three children the eldest is named Mr Liar, the second Mr Thief and the third Mr Thug… it is these three persons who ruin the world.”

The new regulation did not spell the end of gambling in Singapore. The new resident, John Crawfurd, who shared the views of his predecessor, saw gambling as a necessary evil and an invaluable source of income to cover the administrative costs of running the settlement. In 1820, when the gambling farms began operating under Farquhar, the amount collected was 5,275 Straits dollars. The figure rose three-fold to $15,076 in 1823 after Crawfurd reinstated the gambling farms; and it further doubled to $30,390 in 1826, reaching $71,283 a year later. In its time, the revenue yielded from the gambling farms exceeded all other forms of excise revenue.

It was not until 1829 that gambling was outlawed for good in the Straits Settlements and gambling farms in Singapore were closed down. Despite the threat of prosecution, the enthusiasm for what was regarded as “one of the curses of the Colony” continued unabated. The prohibition of gambling only served to drive it underground, where it thrived due to the weakness and ineffective enforcement of the law.

“The love of gambling is inherent in the Chinese. Men, women and children are addicted to the vice,” wrote J. D. Vaughan in The Manners And Customs Of The Chinese In The Straits Settlements (1879). Around the time of his writing, there were reportedly no fewer than 10 types of gambling games in Singapore, including lotteries, cards, dice and dominoes. Colonial administration often held the view that gambling was an inborn trait of the Chinese. However, the observations of G.T. Hare, former Assistant Protector of Chinese in the Straits Settlements, suggest how the Chinese penchant for gambling could be better understood:

“One’s length of days here is, to (the Chinese) mind, but a long game where the cards are always changing. Gambling seems to clear his mind and brace his nerves. It is training ground to him for the real gamble of life.”

The socio-economic circumstances of immigrant life inadvertently conditioned the propensity of the Chinese to gamble. Fleeing poverty and unrest in their homeland in the 19th century, Chinese immigrants arrived by the boatload, swelling the ranks of unskilled labourers in Singapore. In his study on Chinese rickshaw coolies, James Warren asserts that gambling “was an inevitable fact of life in a migrant community bereft of family life (and) comprised largely of restless adult men with time on their hands and money to burn”.

With few options for wholesome recreational activities, gambling went hand-in-hand with drinking, opium smoking and prostitution – the “four evils” – as the main sources of entertainment and escape from the drudgery of everyday life for these men. Earning a pittance for back-breaking work with little rest, they nevertheless dreamt of returning to China with a fortune; the hope of winning a game or lottery was a psychological balm that made their grim existence more bearable.

It was only a matter of time before the gambling habit exacted its price. Having squandered their hard-earned money, the men borrowed heavily from their employers to feed their gambling addiction. Mired in debt, they invariably pledged to continue working for their creditors until the sum was paid up. Without personal savings, it was impossible for sons, brothers and husbands to fulfil their moral duty of providing for their dependants back home and this failure became the cause of untold family strife and tragedy. It was no surprise that, when driven to desperation, many resorted to theft, violence and crime – and, when all was lost, suicide.

THE BRAINS BEHIND THE BUSINESS

Writing at the end of the 19th century, Hare likened gambling in Singapore to epidemics that “break in waves from time to time over the surface of Chinese life, carrying trouble and distress with it”.

He thought it expedient to document the latest fever among the immigrants and Straits Chinese over a new form of gambling called chap ji kee “before it passes away out of men’s minds and becomes one of the dead ghosts of the forgotten past”. Chap ji kee is Hokkien for 12 Cards where chap ji means “12” and kee refers to the card. While its origins can be traced to the game of Chinese cards, popular in the southern Chinese province of Fujian, the evolution of chap ji kee into a large-scale underground lottery in Singapore was an innovation that Hare attributes to Peranakan or Straits Chinese women (nonyas).

According to him, chap ji kee was first played in Johor before catching on in Singapore in 1893; it was suppressed only three years later when the authorities began stamping it out.

The game operated in the manner outlined until 1894 when, as Hare claims, it became much altered by the nonyas who emerged as its chief organisers and top patrons. As the popularity of the game grew, chap ji kee was modified in order to evade detection by the authorities and make it difficult to prosecute the offenders. To circumvent the law, the promoters would engage a number of collectors who went from door to door taking bets from private homes, thus obviating the need for punters to gather in one place to stake their money in person. To avoid being caught with evidence of the lottery on their bodies, collectors rarely carried the chap ji kee cards with them and further devised their own cryptic notations to keep track of various accounts. For example, the value of 10 cents was denoted by a circle, and a dollar by a cross inside a circle. Their symbols were combined or doubled to represent higher values.

Likewise, chap ji kee characters were represented in a variety of ways such as written and pictorial symbols, strings of beads, numerals – even the number of spots on a certain type of handkerchief carried by nonya ladies could surreptitiously function as a code.

THE MODUS OPERANDI

After gathering the bets, the collectors would assemble for the drawing of the lottery at a place and time decided in advance by the producer. Houses that afforded some means of quick escape through a back door or over the roofs of neighbouring houses onto the streets were usually selected as the venue.

With informants hired to keep a lookout for the police, the game would commence after the front entrance had been secured and the whole party was ensconced in a room upstairs or on the ground floor at the back of the house. The packets containing the stakes and betting memoranda would be laid on a table in front of the promoter, who would proceed to announce the winning character from the selected card. The group quickly dispersed once the winnings were paid out.

The role of collector was greatly sought-after for the steady income it brought; collectors typically earned a 10 per cent commission on every winning stake. Profit margins were high as some lotteries did not restrict the amounts staked. It helped of course that the clientele comprised mainly affluent Straits Chinese ladies with ample leisure time and money to spare. Their healthy appetite for gambling came to public attention in several notable police court cases: In 1909, for instance, when 11 nonyas were arrested in a house in Tank Road for playing chap ji kee, the magistrate – who felt that the maximum fine of $25 was grossly inadequate as punishment – sagely advised their husbands to let the women be imprisoned for two weeks instead of paying a fine. In another interesting case, the wife of a wealthy Chinese gentleman pawned her jewellery to settle a $50,000 chap ji kee debt – a sizeable fortune even by today’s standards – and had the items replaced with cheap imitations.

The success of the chap ji kee lottery spawned a franchise of sorts. Enticed by the lure of easy money, enterprising individuals opened sub-agencies or branch firms, declaring the same winning number announced by the main syndicate. Unlike the principal chap ji kee, the sub-agency was open to the general public and run by men as well as women. In time, an elaborate three-tier system of promoters, sub-promoters and collectors was established.

Over time, chap ji kee further evolved to attract a wider audience: The Chinese characters were replaced by the numbers 1 to 12, ensuring that even the illiterate could play, and instead of betting on a single character, punters would stake their money on a pair of numbers between 1 and 12. This meant that a punter had to correctly guess two winning numbers. At 1 to 144, the odds of striking seemed more remote than before, but to sweeten the deal, the dividend was increased to 100 times the size of the stake. To attract as many punters as possible, the minimum bet would be as low as one cent, which over time increased to 10 cents.

The combination of small bets and high returns made chap ji kee irresistible to low-wage workers and housewives. Punters did not need to pay the full amount of their bets immediately as collectors generally extended some form of credit. It was easy to place bets as anyone could qualify as a collector – the stall-owner in the market, the hawker on the street corner, the bored housewife and even the washerwoman. The system worked because the arrangement was based on tacit trust: Collectors never issued receipts, and most punters neither knew who drew the winning numbers nor where the draw took place. The winning numbers would be scribbled on walls or pillars in designated areas or conveyed by word-of-mouth in the streets. A collector who was the proprietor of a coffee shop even used a wall clock to display the results – the hour and minute hands would point respectively to the first and second winning numbers.

The odds were always rigged in favour of the syndicates as they would regularly choose the least-backed number as the winning one. This was achieved by having each sub-promoter draw up a schedule containing all the betting configurations and stakes that the collectors had gathered. These were then consolidated into a master schedule that enabled the promoter to easily determine the combination with the lowest stakes among the 144 possible permutations. Such a practice guaranteed consistent profits for the syndicate.

THE LURE OF CHAP JI KEE

Chap ji kee flourished in the post-war decade with estimated takings of a whopping half a million dollars a day. The scene was dominated by two syndicates – Lau Tiun, which controlled the Tiong Bahru and Upper Serangoon Road areas, and Shanghai Tai Tong that held sway over the rest of Singapore. In 1948, the authorities brought the latter to its knees with the arrest and deportation of its ringleaders.

However, the break-up of this powerful syndicate managed to disrupt the chap ji kee business for only five days before others swiftly stepped in to fill the vacuum. The former associates of Shanghai Tai Tong split into two syndicates – Sio Poh, Hokkien for “Small Town” and Tua Poh, Hokkien for “Big Town”, which operated in the areas north and south of the Singapore River respectively. By the 1970s, the Lau Tiun, Sio Poh and Tua Poh syndicates were ranking in a combined annual turnover of $100 million. It is little wonder that chap ji kee had been called a “colossal swindle”.

Aside from the enormous sums of money involved, the lottery was an outright scam since a win was determined by deliberate choice rather than random chance.

Yet, punters remained undeterred. In 1973, the New Nation tabloid interviewed 200 gamblers and found that 95 per cent knew how the winning numbers were derived. Quite incredulously, when asked the reason for their continued participation, the respondents, most of whom were housewives, explained matter-of-factly:

“Chap ji kee is the only form of gambling that we can take part in daily without too many objections from our husbands, unless we bet heavily. The stakes allowed are small. It is convenient and it happens daily. All we have to do is tell the collectors, some of whom are people we meet every day on our market rounds – the vegetable sellers or fishmongers”.

Chap ji kee was called the “housewives’ opium” as it was an easy way of injecting some excitement into their lives and to relieve the tedium of domestic chores and child-minding. Although the women played for low stakes and did not realistically expect a windfall from chap ji kee, the prospect of winning just that little extra cash was attractive enough for the average housewife with fairly modest wants – “that special meal, a new dress for baby or that much-desired gold ring for herself”.

The principles of an honest game did not concern the (wo)man in the street. In their minds, chap ji kee was still based on chance since the combination of numbers that was likely to attract the least stakes was anyone’s guess. The syndicates, which pocketed at least 80 per cent of the annual turnover, were clearly the indisputable winners – so long as their luck held.

THE DEATH OF CHAP JI KEE

The authorities tried to stamp out chap ji kee for years but to no avail. The key to the game’s longevity lay in the well-organised syndicates and their covert operations as well as the intricate network of collectors who did the dirty work on behalf of the promoter. It would take two decades and the progressive tightening of the law and relentless police raids throughout the 1960s and 1970s before chap ji kee rackets were smashed. The syndicates gradually disintegrated as the kingpins and their close associates were arrested or went into hiding.

In addition, the creation of legal lottery operator, the Singapore Pools, in 1968 and the introduction of state-run lotteries beginning with Toto that year, gradually chipped away the syndicates’ customer base. Since history has shown that gambling cannot be completely eradicated, the Government took a pragmatic approach and introduced legalised gambling options; at least this way, gambling could be regulated and the revenue channelled towards worthwhile and civic causes. The first project funded by Singapore Pools was the construction of the National Stadium. Today, the Tote Board (Singapore Totalisator Board), which was formed in 1988, channels the surpluses from these state-run lottery operations to support public, social or charitable causes, as well as the growth of culture, art and sport in Singapore.

While it is entirely plausible that chap ji kee might still be played in some isolated circles today, there is little chance of the game ever regaining its former glory. To recall Hare’s words, chap ji kee has been cast “out of men’s minds and (has become) one of the dead ghosts of a forgotten past”.

http://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/desperate-housewives-and-the-lure-of-chap-ji-kee

Chillas people lets talk slow…… love history!!!!!!!!!!!!

Showed out in my HI paper.