The Last Kampong on Mainland Singapore

Lorong Buangkok was originally a swampy area. In 1956, a traditional Chinese medicine seller named Sng Teow Koon bought a piece of land at Lorong Buangkok and rented it to several Chinese and Malay families, which gradually formed a kampong over the years.

The closely-knitted kampong went through the racial riots of the sixties. Both the Chinese and Malay residents agreed to look after one another during the turbulent periods and keep the village unaffected by the external chaos. When the peaceful time returned, the village was actively engaged in gotong royong, helping each other in the construction and repairs of houses.

Today, the piece of land that Kampong Lorong Buangkok is standing on, about the size of three football fields, is owned by Sng Mui Hong, the daughter of Sng Teow Koon. Around 28 families are still living in this rustic village, paying tokens as monthly rentals to the landlord. There is also a kampong head, who takes care of the surau, daily prayers and other Muslim affairs within the village.

Flood-Prone Area

Lorong Buangkok has been a low-lying area that is prone to flooding during thunderstorms. So much so that Kampong Lorong Buangkok was once also known as Kampong Selak Kain, which means “lifting up one’s sarong” in Malay, as the residents had to lift up their sarongs to their knee levels in order to walk through the waters during the flooding.

In 1976, the kampong was hit hard by a downpour that lasted three hours. Some 40 Malay families were affected and had their Hari Raya preparation ruined as their beds, furniture and curtains were soiled by the flood water that covered the entire lorong.

History of Lorong Buangkok

Lorong Buangkok used to be part of the Punggol constituency, represented by Ng Kah Ting who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Punggol for 28 years between 1963 and 1991.

In 1978, after several requests, the government approved a $770,000 project to metal 15 muddy trails at Lorong Buangkok and Cheng Lim Farmways. The upgrading took almost three years. By the early eighties, the residents of Punggol and Lorong Buangkok finally had new tarmac roads flanked by brightly-lit street lamps.

The Cheng Lim Farmways was a network of roads between farms and plantations at the southern part of old Punggol (where Sengkang’s Anchorvale neighbourhood is today), linked by a small trail named Lorong Buangkok Kechil (kechil means “little” in Malay). Lorong Buangkok had its network of farmways too; there were Buangkok North Farmways 1 to 4 and Buangkok South Farmways 1 to 4.

On the eastern side of Lorong Buangkok were the Seletar East Farmways, which had been redeveloped into the Fernvale neighbourhood of Sengkang. To cross over to either side, the residents and farmers of Lorong Buangkok, Cheng Lim and Seletar East made use of a simple bridge that spanned across Sungei Tongkang, an extension of the main Sungei Punggol.

Sungei Tongkang – From Stream to Canal

For years, the sluggish and narrow Sungei Tongkang was the main cause of the numerous flooding at Kampong Lorong Buangkok. The stream tend to overflow during downpours. In 1979, the Ministry of Environment’s Drainage Division decided to widen and deepen Sungei Tongkang, and convert it into a canal at a cost of around $1.8 million. Works were also carried out at the upper and lower parts of the river to ensure the water flowed smoothly.

Despite the upgrading, the kampong still suffered from occasional floods. It was especially hit hard by one as recent as 2004.

All the farmways above-mentioned were expunged by the early nineties, with their vegetable, chicken and pig farms demolished. The clusters of villages scattered around Lorong Buangkok, Cheng Lim and Seletar were also gone, making way for the development of the Punggol and Sengkang New Towns in the late nineties.

The housing estates of Fernvale, Anchorvale and Buangkok Crescent were up and running between 2002 and 2004, surrounding Kampong Lorong Buangkok, the last village standing in the vicinity. A jogging track and park connector were constructed in the late 2000s along the canal that was previously Sungei Tongkang.

Development and Possible Demolition?

By the mid-2014, the vast forested area beside the kampong was bulldozed, confining the Kampong Lorong Buangkok to its remaining strip of vegetation sandwiched between the canal and the cleared land. The new parcel of land is likely to be reserved for an extension of the existing Buangkok Crescent housing estate.

As for the kampong, it is not sure how much longer it will be able to hang on. After withstanding the test of time for the past 60 years, the clock, for now, seems to be ticking fast on Kampong Lorong Buangkok’s eventual demolition as development is inching ever closer to the last village of Singapore.

Updated: 13 January 2015

That’s incredible: i didn’t realise there was still a kampong left in Singapore!

I used to live at Lorong Buangkok near the junction towards Ponggol Road. I spent my childhood riding on my bicycle regularly to the other end of Lorong Buangkok towards Yio Chu Kang Road, near where the last kampong sits. Along the way were many houses and farms that lined both sides of the road and my best memories were the rubber plantations, the Ponggol Theatre, the Soo Teck School and a temple that once housed a large python that was caught nearby. Despite the narrow road, we cyclist had to be alert and had to keep to the side of the road as there were always large trucks carrying live stocks plying the area. Later, the road was also congested with military three tonnes ferrying soldiers as the SAF regularly conduct deployment and various exercises there. Pity that I don’t have the places on film as I did not own a camera then,, Would appreciate if anyone has pictures or memories to kindly share.

Hi, You may try to get Old News paper (Lianhe zaobao) from library.

Dated: 1st November 1987 (Sunday).

Singapore government should just leave it as it is. Come on, it’s the last kampong in Singapore!

I feel sad for it as much as I do for the “old” Punggol and Sengkang. No more forests and peace anymore.

Went to this kampong again last week, after having a relaxed coffee session @ the kampung kopitiam @ Seletar camp… Still so peaceful and serene….. I think that if we are able to hold a bbq session @ one of the villager’s house.. would be so wonderful..but i doubt its even possible..

This is sad. Every last piece of free land must remake to something with high profit and ROI. Kampong, hawker centre, swimming pool, public square, forest, shophouse all must go. Singapore loses history to $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$.

People need comfortable places to live, but a paved paradise, put up a parking lot? Who can save these people and their wish to pursue a simpler life?

Hopefully this remain there for as long as possible. Found a short interview video on youtube of Sng Mui Hong – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_SeBc36Y57E

Updates as the Feb BTO for Buangkok has just been announced today on 11 Feb. Please see attached map:

Not too big of a concern for Buangkok Tropica, but Buangkok ParkVista is seriously close, or if not right at the Kampong site. Judging from the not-to-scale map, it means that the kampong houses are being squeezed to its houses only! The worst of all is the proposed semi-expressway which still runs directly across the kampong. So conclusively, it is goodbye to this place soon 😦

I suggest we start a petition to keep the kampong safe from future developments. Come on, this is somewhat a national heritage! Once the government suck it up for money, it can never be replaced ever again

I like the villages in Singapore but unfortunately there is no responsible party maintain villages.

Hi, am thinking of doing a casual photoshoot at the kampung together with my puppy. wonder if it is allowed?

we wish to bring a group of kids there to have a look. Is there any way we can contact the landlord?

Would anyone take offence if an ‘outsider’ visited to take casual photographs?

It’s probably okay to take photos of the exteriors of the houses but don’t attempt to trespass others’ properties, eg entering their premises without permission 🙂

Way to go Mr Singaporean Government. Surely you can squeeze an extra floor onto a few of your ugly concrete boxes and leave the last remaining trace of your old world alone. If you do then you can at least have a small slice of old Singapore instead of an island completely covered in copies of stuff from the rest of the world.

If you look at some of the newest BTOs, some of the lower storeys are left empty where HDB could have easily turned them into actual units which makes NO sense at all, especially when the government has been emphasing just how land scarce we are since forever.

As someone who grew up in kampungs, I feel very sad that the greedy govet won’t leave this last remnant of our national history alone. Greed is good ? Total lack of conscience for our children and grandchildren to see a living example of how their parents/grandparents grew up. No legacy for our kids to understand an appreciate. what a terribel loss for Singapore if this last kampong is paved over for GREED.

Singapore’s Last Surviving Village

BBC Travel

26 May 2021

If you turn off the busy Yio Chu Kang road in north-eastern Singapore and follow a long, earthen path that winds and snakes for about 300m, you will find something of a time capsule. Nestled here, on three acres of verdant land, is Kampong Lorong Buangkok, Singapore’s last surviving village, where remnants of the 1960s are alive and well. Little resembles modern-day Singapore’s panorama of slick skyscrapers. Instead, the cluster of squat bungalows looks like a vintage postcard of the city’s yesteryear.

The kampong – which means “village” in Malay – is a rural oasis in a city-state synonymous with urban sprawl. Roughly 25 archetypal wooden, single-storey dwellings with tin roofs are spread around a surau (small mosque). Forgotten flora that once covered Singapore before all the concrete – like the ketapang, a native coastal tree – grow freely. Nearby, power cables hang overhead, a rare sight since most have gone underground in the rest of the city. Elderly residents sit out on their verandas; chickens in their coops cluck endlessly away; and the chorus of chirping crickets and crowing roosters – the sounds of a bygone era – drown out the city’s noise pollution and provide a soothing, bucolic soundtrack.

Rustic idyll isn’t what usually comes to mind when most people think of Singapore today. Rather, it’s the boat-shaped Marina Bay Sands towers, the soaring skyline, or the colourful and futuristic Gardens by the Bay. Yet, until the early 1970s, kampongs like Lorong Buangkok were ubiquitous across Singapore, with researchers from the National University of Singapore estimating there were as many as 220 scattered across the eponymous island. Today, while a few still exist on surrounding islands, Lorong Buangkok is the last of its kind on the mainland.

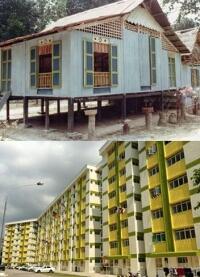

A young nation with international aspirations, Singapore rapidly urbanised in the 1980s and quickly transitioned from an agricultural to industrial economy. Overcrowded shophouses were replaced with high-rise flats and sprawling skyscrapers, ushering in the so-called “era of expressways” that saw small roads replaced with multi-lane highways across the city-state. With land at a premium on the island, the rural kampongs had to give way.

And so hundreds of traditional villages were bulldozed, the native flora stripped, earthen paths levelled and livelihoods razed to the ground as part of a government-wide resettlement programme. Village residents – some reluctant to give up their valuable real estate; others eager to swap countryside living for flushing toilets and running water – were herded into government-built subsidised flats erected atop their old homes. Today, more than 80% of Singaporeans live in these structures.

With the rural villages’ demolition also went the famed “kampong spirit”, a term used by Singaporeans to describe the culture of camaraderie, trust and generosity that existed within them. In kampongs, residents didn’t need to lock their doors and families welcomed neighbours, who often stopped by unannounced to borrow whatever they needed. It’s a way of life that the government has tried to recreate in its apartment blocks by increasing the number of shared communal spaces to encourage social interaction.

In 2017, Singapore’s Housing & Development Board partnered with the Singapore University of Technology and Design to develop a framework for urban kampongs, a high-tech approach that uses motion sensors and shared Wi-Fi spaces to encourage camaraderie among neighbours. Lawrence Wong, the then-minister for national development said one of the goals was to “strengthen the kampong spirit in our high-rise apartments”. But communal living isn’t the only ingredient to foster this friendly spirit; the environment matters, too.

One reason Lorong Buangkok has managed to escape the fate that befell other kampongs is because the surrounding area wasn’t as desirable for commercial, industrial and residential development as elsewhere in Singapore – though that has slowly changed. Once surrounded by a forest clearing and farms, it is now flanked by an enclave of private gated housing and a cluster of flats that overlooks the low-rise settlement.

Another reason became obvious once I met the village’s landlady: a headstrong woman with a resolute commitment to preserve Singapore’s sole surviving kampong.

Approaching 70, Sng Mui Hong, has lived nearly her whole life in the village. She is the youngest of four siblings, and only one who has stayed here. Her late father, a traditional Chinese medicine seller, purchased the land in 1956, the same year the village was created and nine years before Singapore gained independence.

According to local guide Kyanta Yap, who leads tours through the kampong, the majority of the plots were leased out to workers from the nearby hospital and rubber plantation – many of whose descendants still reside here. Back then, monthly rent for each house was between S$4.50 and S$30 (£2.40-16.20). Today, Sng still charges Lorong Buangkok’s 25 families more or less the same rate. By contrast, renting a room that’s roughly one-tenth the size of a kampong house in an adjacent government-built block might cost about 20 times that amount. And the houses across the dividing canal can sell for upward of a few million Singaporean dollars.

While the village has arguably the most affordable housing in Singapore, no new occupants have moved in since the 1990s, and there’s a slim chance there will be any in the near future. As Yap told me, residency is conditional: someone generally has to move out or pass away for a home to open up, and then only those with a connection to either past and present tenants or Sng’s family are considered.

Since Singapore emerged from lockdown last June, Yap has noticed an increasing interest in Lorong Buangkok and his weekend tours now quickly fill to capacity.

“It’s not that surprising since no-one can travel, and this is a unique local tourist spot,” he said. “There are also many who visit on their own; the general public, bikers, joggers and even groups organised on Meetup.” Yap said most come to take a serene walk through the kampong, snapping photos of a rare green oasis tucked away in one of the world’s most-densely populated and urbanised countries.

Yap added that the secluded, tight-knit community of 25 households who live in the kampong have now grown used to the steady stream of curious passersby.

Though Lorong Buangkok may represent an intriguing time capsule for many Singaporeans, it represents something much more for Sng. She recalled following her father around as a child while he tended to this land. It was from him that she picked up the knowledge of traditional Chinese medicine that she now shares with her neighbours. Leaves from the village’s henna plants, for example, can be used to soothe open wounds and burns, and they are also believed to protect against intestinal ulcers when ingested.

Sng knows she’s sitting on hot property. In a country so starved of space, there has been no shortage of developers hoping to purchase the village. But no offer will ever be attractive enough for her to retract a promise she made to her dying father – to preserve Lorong Buangkok. She reiterated a stance she’s defended for decades, and one her siblings, who frequently come back to visit, fiercely share: for as long as she can help it, this land is not up for sale.

In 2014, there was a proposal to raze the village and replace it with a highway, two schools and a public park. Though the government may still consider the plan, the Minister for National Development, Desmond Lee, has also stated that there is “no intention to implement these developments in the near future”.

Many Singaporeans have voiced their objections to the proposed plan. Others have even pushed for the village to be included as a Unesco World Heritage site. But while kampongs were once widely regarded as “deplorable” by the Singapore government, there’s now a newfound appreciation by officials for these rural relics and the culture they foster.

“Lorong Buangkok could be retained as part of the schools for outdoor learning activities for example, or integrated into future parks or playgrounds,” explained Dr Intan Mokhtar, a former politician and current assistant professor in policy and leadership at Singapore Institute of Technology. “Most [residents] have lived there for more than half of their lives, and they treat one another as family.”

At the very least, Singaporeans have the government’s word that it will approach the matter thoughtfully. “When the time comes for us to finalise our plans for the entire area, the government should work closely with relevant stakeholders to ensure developments are carried out in a holistic and coherent way,” Lee has said. “This must involve deep engagement with the kampong families living there at that time, to understand and consider their needs and interests.”

One of the kampong’s residents, Nassim, told me that, “It’s good the government now sees the importance of our kampong.”

“You need to leave something behind that reminds our young of how this country came about. We came from these humble huts.” Nassim added that it’s also a good thing that Sng, once much more reclusive, now welcomes the public to her land. “It helps them understand us and understand why Lorong Buangkok needs to be preserved.”

In Singapore, where land is a precious commodity, there will always be tension between keeping the old and developing the new. While the future of Lorong Buangkok remains uncertain, saving it means safekeeping a glimpse of the nation’s roots, culture and heritage for future generations – something that’s necessary even for a country as young as Singapore.

http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20210525-singapores-last-surviving-village