With intensive usage of media, campaigns are launched to achieve certain particular goals, usually in a political, social or commercial sense. Sometimes, a campaign represents an era, and some of its posters go on to become iconic representations that are even remembered after decades. One of the examples is the United States’ “I Want You For U.S. Army” poster in 1917.

With intensive usage of media, campaigns are launched to achieve certain particular goals, usually in a political, social or commercial sense. Sometimes, a campaign represents an era, and some of its posters go on to become iconic representations that are even remembered after decades. One of the examples is the United States’ “I Want You For U.S. Army” poster in 1917.

Campaigns are meant to have a long term impact. However, human errors, wrong judgement or a lack of foresight during the introduction of campaigns can sometimes lead to failures or even disasters to the country. In 1958, the new China launched the Four Pests Campaign in a bid to eliminate rats, flies, mosquitoes and sparrows. The sparrows were targeted because they ate the farmers’ grain seeds. In a short time, millions of Chinese were mobilised for the campaign. Sparrows, as well as other birds, were shot, with their nests and eggs destroyed. Soon, the Chinese government realised that, besides eating grains, sparrows were also natural predators to many insects. It was too late then. By 1960, rice farms in China were swarmed by locusts, leading to the Great Chinese Famine in which millions died of starvation.

Campaigns are meant to have a long term impact. However, human errors, wrong judgement or a lack of foresight during the introduction of campaigns can sometimes lead to failures or even disasters to the country. In 1958, the new China launched the Four Pests Campaign in a bid to eliminate rats, flies, mosquitoes and sparrows. The sparrows were targeted because they ate the farmers’ grain seeds. In a short time, millions of Chinese were mobilised for the campaign. Sparrows, as well as other birds, were shot, with their nests and eggs destroyed. Soon, the Chinese government realised that, besides eating grains, sparrows were also natural predators to many insects. It was too late then. By 1960, rice farms in China were swarmed by locusts, leading to the Great Chinese Famine in which millions died of starvation.

Singapore had launched over 200 campaigns in the seventies and eighties. Many of these campaigns had positive effects, even till today, such as water-saving, anti-smoking and anti-littering. Below are some of the most memorable Singapore campaigns of the past.

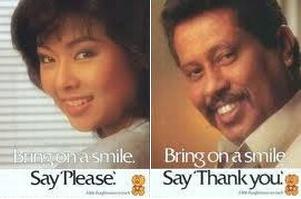

National Courtesy Campaign (1979-2001)

Started by the Ministry of Culture (later Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts, and now Ministry of Communications and Information) in June 1979, the objective of the campaign was to promote a pleasant living environment filled with kind, considerate and polite Singaporeans.

The courtesy campaign was actually kicked off much earlier in the seventies, when Singapore was focusing in developing its tourism sector. Launched by the Singapore Tourism Promotion Board (STPB) to encourage Singaporeans to be polite to the tourists, the successful campaign was “extended” to all aspects so that courtesy and thoughtfulness could be spontaneous characteristics in Singaporeans’ everyday life.

In 1982, the National Courtesy Campaign adopted Singa the Courtesy Lion as their official mascot to replace their Smilely logo. Singa went on to become one of Singapore’s most recognisable mascots in the eighties and nineties, and the designer even added a female companion and three little cubs for Singa in 1987.

Since its debut, the National Courtesy Campaign has introduced many catchy slogans. The first was “Courtesy is our way of life. Make courtesy our way of life.” in 1979, while other popular ones included “A little thought means so much. Bring on a smile. Say “Please/Thank You” (1985) and “Courtesy begins with me” (1989).

Since its debut, the National Courtesy Campaign has introduced many catchy slogans. The first was “Courtesy is our way of life. Make courtesy our way of life.” in 1979, while other popular ones included “A little thought means so much. Bring on a smile. Say “Please/Thank You” (1985) and “Courtesy begins with me” (1989).

A song named “Make courtesy our way of life” was also composed in 1980 by De Souza J.J.

“Courtesy is for free,

Courtesy is for you and me.

It makes for gracious living and harmony.

Giving a friendly smile,

Helping out where we can.

Trying hard to be polite all the time.

Courtesy is for free,

Courtesy is for you and me.

It makes for gracious living and harmony.

Living could be a treat,

If people are awfully sweet.

Courtesy could be our way of life.

It is rude to be abusive,

Just to prove we’re right.

Instead we could be nice about it if we tried.

Courtesy is for free,

Courtesy is for you and me.

It makes for gracious living and harmony.

Living could be a treat,

If people are awfully sweet.

Courtesy could be our way of life.

Make courtesy our way of life!”

The music clip is available at http://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/music/music/track/ebdd7595-bd86-4f7c-8b4d-f7f9c47e83b0.

In March 2001, the National Courtesy Campaign was officially replaced by the Singapore Kindness Movement (SKM). Former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong highlighted in the New Year of 1996 that Singapore aimed to become a gracious society by the 21st century.

In March 2001, the National Courtesy Campaign was officially replaced by the Singapore Kindness Movement (SKM). Former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong highlighted in the New Year of 1996 that Singapore aimed to become a gracious society by the 21st century.

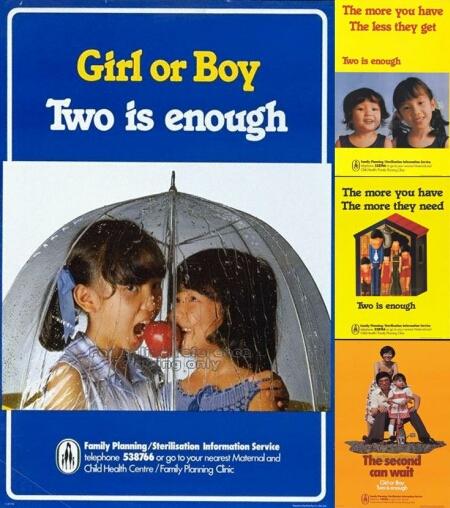

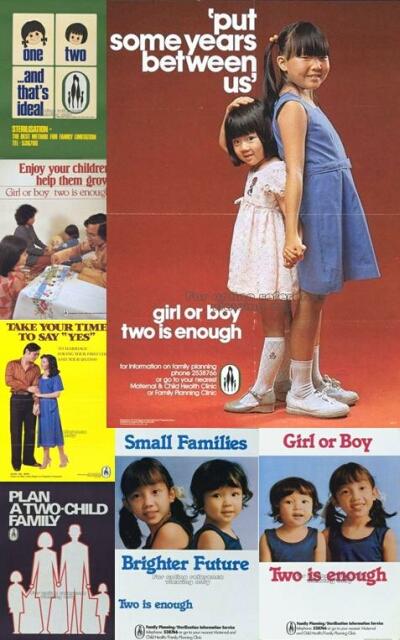

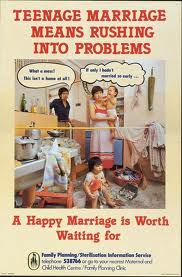

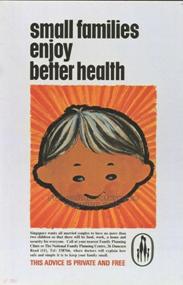

Stop At Two (1970-1986)

The poster with two sisters sharing an apple under an umbrella was perhaps the most iconic media representing Singapore’s population control campaign of the seventies and eighties.

After the Second World War, Singapore experienced a post-war baby boom. Overcrowding became a social issue, leading to various problems in housing, education, medical and sanitation. After Singapore’s independence, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew was concerned that the uncontrolled growing population would put stress on the economy of a developing Singapore. Thus, the National Family Programme was launched with the Family Planning and Population Board (FPPB) established in 1966.

After the Second World War, Singapore experienced a post-war baby boom. Overcrowding became a social issue, leading to various problems in housing, education, medical and sanitation. After Singapore’s independence, former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew was concerned that the uncontrolled growing population would put stress on the economy of a developing Singapore. Thus, the National Family Programme was launched with the Family Planning and Population Board (FPPB) established in 1966.

The campaign reached its peak after 1970, when abortion and sterilisation were legalised. Women deemed low-educated with low incomes were urged to go for sterilisation after their second child, and a range of disincentives, such as lesser benefits in maternity leaves, housing allocations, tax deductions and children’s educations, was implemented for those had three or more. The campaign also aimed to discourage families to stop trying for a boy after having two girls.

The campaign reached its peak after 1970, when abortion and sterilisation were legalised. Women deemed low-educated with low incomes were urged to go for sterilisation after their second child, and a range of disincentives, such as lesser benefits in maternity leaves, housing allocations, tax deductions and children’s educations, was implemented for those had three or more. The campaign also aimed to discourage families to stop trying for a boy after having two girls.

It was perceived that the “Stop At Two” campaign was targeted at the uneducated batch of citizens who were deemed to contribute lesser to the economy. The introduction of the Graduate Mothers’ Scheme in 1984 provided further proof when the government encouraged the male Singaporeans to choose higher-educated wives and gave out more incentives for higher-educated mothers to have three or more children. Causing an uproar in the public and press, the scheme was eventually scrapped a year later.

The Graduate Mothers’ Scheme was the beginning of the reversal of the population control scheme. In 1986, the Family Planning and Population Board was abolished, and a new campaign “Have Three or More, if you can afford it” was launched. It was predicted that Singapore’s birth rate would recover by 1995. But it never did.

The Graduate Mothers’ Scheme was the beginning of the reversal of the population control scheme. In 1986, the Family Planning and Population Board was abolished, and a new campaign “Have Three or More, if you can afford it” was launched. It was predicted that Singapore’s birth rate would recover by 1995. But it never did.

Some critics note that even without the population control campaigns, Singapore’s birth rate would still decline as the society became more developed. The rising number of higher-educated individuals who were less willing to start a family at an early age would be unavoidable. In any case, it was obvious that the campaign had lasting effects even till today. In recent years, the government relaxed its immigration policy in a bid to battle against an aging population and a shrinking workforce in Singapore, a move that proves to be hugely unpopular among the Singaporeans.

Some critics note that even without the population control campaigns, Singapore’s birth rate would still decline as the society became more developed. The rising number of higher-educated individuals who were less willing to start a family at an early age would be unavoidable. In any case, it was obvious that the campaign had lasting effects even till today. In recent years, the government relaxed its immigration policy in a bid to battle against an aging population and a shrinking workforce in Singapore, a move that proves to be hugely unpopular among the Singaporeans.

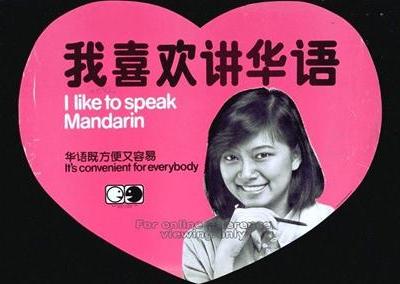

Speak Mandarin Campaign (since 1979)

The Speak Mandarin Campaign was officially started in September 1979 by former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. Originally designed as a ten-year program, the campaign was headed by Dr Ow Chin Hock and was targeted at the Singaporean Chinese, which made up almost 3/4 of the country’s population.

The early Chinese immigrants in Singapore largely came from the southern provinces of China, and spoke mainly in dialects such as Hokkien, Cantonese, Teochew, Hakka, Hainanese and Hockchew. In the 19th century, different Chinese communities often clashed against each others over territories and businesses. One of the major conflicts was the Hokkien-Teochew Riots in 1854, which lasted 10 days and caused 500 casualties. The differences between the various dialect groups became less defined by the late 1930s, when the oversea Chinese united together to aid China financially against the invasion of Japan.

In the late seventies, English was determined as the mainstream for a bilingual education in Singapore, with “mother tongue” used as the second language. Mandarin was deemed as the mother tongue for all Singaporean Chinese. Slogans and posters were put up in public places, while civil servants were ordered not to use dialects during working hours. Parents were encouraged to use hanyu pinyin names for their children, instead of names in dialects. Dramas, movies and radio programs in dialects were gradually phased out, with only a few exceptions.

The classic theme song of the early Speak Mandarin Campaign “大家说华语” was definitely memorable for many Singaporeans growing up in the eighties. The song was composed in 1980 by Taiwanese composers Feng Qingxi (music) and Sun Yi (lyrics), and performed by Taiwanese songbird Tracy Huang Yingying.

国家要进步 语言要沟通

就从今天起 大家说华语

不分男和女 不分老和少

不再用方言 大家说华语

听一听 记一记

开口说几句 多亲切 多便利

简单又容易

The government attempted to change the names of some places in Singapore to the standard Chinese hanyu pinyin format in the late eighties. The move was, however, backfired, when there were numerous complaints about the renaming of Nee Soon, Tekka and Bukit Panjang to Yishun, Zhujiao and Zhenghua respectively.

By the nineties, the Speak Mandarin Campaign had a change of objective. It was targeted at a growing number of working class and professionals who preferred to use English solely as their spoken language. The government became worried that this group of Singaporean Chinese, who had received the mainstream English education in their early days, were beginning to lose their roots in the Chinese heritage and culture. It also created a divided society, where the English-speaking population looked down on their fellow Chinese-educated and lower-income Singaporeans.

Chinese dialects, along with Malay and some local expressions, largely make up Singlish, the localised language that is easily identifiable among the Singaporeans themselves. In order to encourage Singaporeans to speak proper English, former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong launched the Speak Good English Movement (SGEM) in 2000. However, studies had shown that many Singaporeans are able to switch between standard English and localised English (Singlish) easily, and therefore Singlish, as an unofficial yet important ingredient of a unique Singapore identity, should not be suppressed or eliminated.

The Speak Mandarin Campaign has been a controversy since its introduction. Some critics view it as a propaganda tool to eliminate the Chinese dialects. It was a dilemma for the Singapore government in the seventies. While it was great foresight to predict the rise of China and the importance of Mandarin as a common language, the danger of Chinese-dominated institutes being used as breeding grounds for communist ideas meant that the authority was always quick to act.

The Speak Mandarin Campaign has been a controversy since its introduction. Some critics view it as a propaganda tool to eliminate the Chinese dialects. It was a dilemma for the Singapore government in the seventies. While it was great foresight to predict the rise of China and the importance of Mandarin as a common language, the danger of Chinese-dominated institutes being used as breeding grounds for communist ideas meant that the authority was always quick to act.

Chinese dialects in Singapore has been in an awkward status for many years. While the likes of Cantonese operas and Teochew wayangs were not restricted in public places, mainstream media such as television and radio were banned, with few exceptions, from broadcasting programs in dialects since the early eighties. Hong Kong and Taiwanese dramas are not allowed to be shown on TVs in their original Cantonese and Taiwanese Hokkien (Minnan), and have to be dubbed in Mandarin. Such rules, however, are not applied on foreign-language dramas from Japan and Korea, which gave audiences an option in dual sounds. Likewise, J-pop and K-pop music are allowed to be aired on radio, but not Cantopop and Taiwanese Hokkien songs.

In just two decades between 1980 and 2000, the usage of Chinese dialects at home had dropped from 80% to 30%, resulting in the current situation where the majority of the new generation of Singaporeans having difficulties to engage in conversations with their grandparents.

Keep Singapore Clean Campaign (1968-1990)

Started as early as October 1968 by former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, the Keep Singapore Clean Campaign was one of the first campaigns launched by the government. Various ministries and non-government organisations were involved, led by then Health Minister Chua Sian Chin, to instill the importance and awareness of environmental cleanliness to the public. The objective was to make Singapore the cleanest city in the region, in order to boost tourism and the attraction of foreign investment.

The Keep Singapore Clean Campaign had a positive impact throughout the years, tackling many issues such as mosquitoes, pollution, inconsiderate littering, street hawkers and sanitation. Posters and banners were displayed, while seminars and spot checks were carried out. Competitions such as the cleanest offices, toilets, buses and taxis were organised. On the other hand, the dirties places were also named in the media so as to apply social pressure to their owners.

A decade-long campaign was also launched between 1977 and 1987 to clean up the Singapore River and the Kallang Basin. By the mid-eighties, most tongkangs and twakows in the Singapore River were cleared, and garbage in the waters removed. The river was clean enough that a mass swim was organised in 1984.

The success of the campaign ensured its continuity till today. It was merged with the Garden City Campaign in 1990, and into the 2000s, it evolved to become the Clean and Green Singapore, which aims to inspire Singaporeans in caring and protecting the living environment.

Public Health Campaign (since 1969)

Public health was one of the top priorities in the government’s agendas after independence. It first covered areas such as dental, heart, disease control, anti-drug abuse, and later extended to anti-smoking, AIDS, mental, workplace health promotion and healthy lifestyle.

Dental Health

The Ministry of Health kicked off the Dental Health Programme in 1969. The standard of dental hygiene was poor in the sixties, with reports indicating that half of Singapore’s population was unaware of proper tooth-brushing, and half of the students did not own toothbrushes. Compulsory tooth-brushing was therefore carried out in all primary one across the country. Students were supplied with toothbrushes and mugs, while teachers were trained to teach proper techniques to their classes. The exercise was a success; in 1973, the programme was extended to all kindergartens in Singapore.

National Heart Week

With the establishment of the Singapore National Heart Association (present-day Singapore Heart Foundation) in 1970, the National Heart Week has been held annually till today. The aim was to promote the awareness of heart disease, its causes and the preventive measures. Deaths related to cardiovascular diseases had been one of the top killers in Singapore. The campaign touched on various aspects in anti-smoking, a balanced and healthy diet, exercises and effective stress management to help reduce the likelihood of high blood pressure and stroke.

Anti-Drugs

Drug abuse had been a major concern in the seventies. The Ministry of Health worked with the Singapore Anti-Narcotics Association to launch a series of anti-drug abuse campaigns to emphasize the dangers and consequences of drugs. From the “Youth Anti-drug” (1971) and “Against Glue-Sniffing and Inhalant Abuse“(1985) to the annual National Anti-Drug Campaign (since 1995), the campaigns had invited showbiz celebrities such as Andy Lau, James Lye and Chen Hanwei to spread the message.

Wash Your Hands

By the seventies, infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, leprosy and cholera were still plaguing the society. The Ministry of Health introduced “Wash Your Hands” campaign to promote self hygiene, disease control and the proper handling of food, especially after visiting the toilets. The relocation of street hawkers took place in the early seventies, with the first hawker centre built (1971) at Yung Sheng of Jurong.

By the eighties, most hawkers plying their trades on the streets were resettled at the new wet markets and hawker centres across the island. There was also significant improvement in the sanitation system. The nightsoil removal service was phased out in January 1987, with the bucket latrine becoming a thing of the past. The measures implemented by the Keep Singapore Clean and Public Health campaigns had greatly improved the cleanliness, hygiene and public health of Singapore.

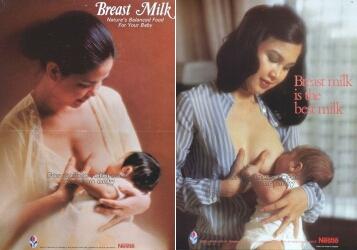

As the standard of living in Singapore gradually improved in the eighties, the focus of public health shifted towards keeping fit, healthy diets, anti-smoking and the benefits of breastfeeding.

Anti-Smoking

One of the campaigns that had little impact since its introduction was the National Smoking Control Programme, started in December 1986 with an objective to make Singapore a nation without smokers. The sale of cigarettes rose dramatically in the seventies and eighties, reaching more than 4 million kg per year. The number of smoke-related deaths, caused by heart disease, lung and nose cancer, also jumped, prompting the Ministry of Health to act.

Other than the aggressive campaign of anti-smoking, the government also issued bans of smoking in certain public places, as well as tobacco advertisements on newspapers, magazines and television. In the later years, more measures continued to be carried out, such as the compulsory printing of graphic photos of the effects of smoking on cigarette boxes, higher taxes of tobacco and extensive banning of smoking in all public places.

Breastfeeding

In the seventies, breastfeeding by Singaporean mothers had fallen to an all-time low. Studies show that it was due to many women entering the working sector. In 1971, only 28% of high income mothers, and 51% of low income mothers, initiated breastfeeding to their babies, as compared to 85% and 90% in the fifties.

In the seventies, breastfeeding by Singaporean mothers had fallen to an all-time low. Studies show that it was due to many women entering the working sector. In 1971, only 28% of high income mothers, and 51% of low income mothers, initiated breastfeeding to their babies, as compared to 85% and 90% in the fifties.

Thus a campaign to promote the benefits of breastfeeding was carried out, but with limited success. While the percentage of high income women who breastfed their babies had increased to 70% by 1980, the low income breastfeeding women dropped to less than 40%.

AIDS Control

While the infectious diseases in tuberculosis, leprosy and cholera were gradually taken under control, the rise of AIDS (Acquired Immuno-Deficiency Syndrome) became a concern in the mid-eighties. AIDS was first discovered by the United States scientists in 1982. The first AIDS-positive case in Singapore was reported in 1985, and the number of such cases increased in a worrying trend. Soon after the first case, the Ministry of Health launched the National AIDS Control Programme to raise awareness of AIDS and HIV (Human Immuno-Deficiency Virus). Many activities were carried out, such as the lifting of the ban of condom advertisements, conducting of blood tests and training of medical and healthcare personnel.

Healthy Lifestyle

The Ministry of Health had consistently encouraged Singaporeans to adopt a healthy lifestyle by emphasizing in food nutrition and regular exercises. One of the first campaigns launched was the Better Food For Better Health Campaign in March 1975. Studies in the eighties show that Singaporeans’ increasing intake of fats had led to a rise in heart diseases and cancers. In 1989, Nutrition Week was introduced. Customers dining in hawker centres were encouraged to request for lesser oil and salt, while school canteens were asked to sell healthier food to students in a bid to battle against obesity.

A series of other health-related campaigns were also launched between the seventies and eighties, such as immunisation for babies, understanding leprosy, awareness against cancer, detection of mental illness and prevention of venereal diseases.

Other than the campaigns mentioned above, there were also dozens of campaigns in other aspects:

Road Safety Campaigns

Road Safety Campaigns

1970 “Queue Up for Safety and Speed”

1971 “Pedestrian Safety”

1971 “Safe Cycling”

1972 “Road Courtesy”

1974 “Reduce Peak Hour Travel”

1974 “Keep Singapore Accident Free”

1977 “Road Safety For You”

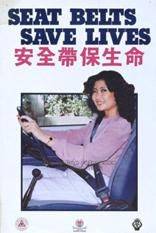

1981 “Seat Belts Save Lives“

Environmental Campaigns

1970 “Tree Planting and Gardening”

1971 “Save Water”

1973 “Keep Our Water Clean”

1973 “National Save Energy”

1974 “Safe Water”

1977 “Energy Conservation”

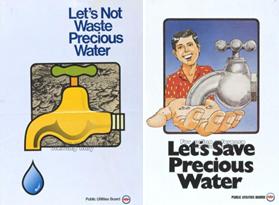

1981 “Let’s Not Waste Precious Water”

1985 “Let’s Save Precious Water“

Social Campaigns

1970 “Crime Prevention”

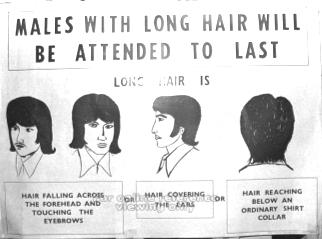

1972 “Campaign Against Long Unkempt Hair Among Males”

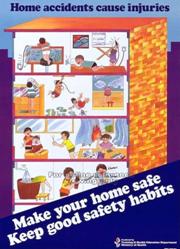

1973 “Home Safety”

1974 “Police Week“

1974 “Keep Singapore Crime Free”

1983 “Home Accidents Cause Injuries“

Workplace Campaigns

1972 “Industrial Safety and Health”

1974 “Building Construction Safety and Health”

1977 “Safety Month for Metal Workers”

1981 “National Productivity Campaign”

1986 “Civil Service Productivity“

Other Campaigns

Other Campaigns

1974 “Anti-Profiteering Against Shopkeepers”

1974 “Go-Metric”

1978 “Eat Frozen Fish”

1983 “School’s Saving Campaign”

1983 “Blood Donation Campaign”

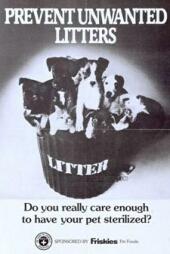

1985 “Prevent Unwanted Litters (Pet Sterilisation)”

1985 “Eat Frozen Pork”

1985 “Minimise Cash Transactions (ATM)”

1985 “Do Not Misuse Accident And Emergency Departments“

(Credit: All pictures from the National Archives of Singapore unless otherwise stated)

Published: 18 January 2013

Updated: 08 August 2020

Discover more from Remember Singapore

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The National Library is holding an exhibition of the past Singapore campaigns:

Campaign City: Life In Posters

From Sharity Elephant to Singa Lion, campaigns and their mascots are an idiosyncratic part of Singapore’s national heritage. Fifty artists, leaders from the creative industry, and students have been invited to design posters by tapping on their personal memories of campaigns. These works are accompanied by a historical survey which features highlights from the National Library’s campaign poster collection.

Until July 7, 10am to 9pm, Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, National Library Building. Free admission. Register for guided tours at library eKiosks or http://golibrary.nlb.gov.sg.

i remember the water conservation poster/sticker. was there something against glue-sniffing?

I think there was (and against chewing gums too), but I couldn’t find any posters of these campaigns

Very good as usual, any interest in doing a piece on the Tanglin of the 80s, I have some photos if you want them>>>>

Sure! Appreciate if you can email to yesterdayom@gmail.com

Nostalgic post. Especially remember the courtesy lion signboards at MRT tracks!

Nice article, remember when I am a small boy when Singa the lion is dance in one of the shopping centre during school holiday.

I remember the frozen fish campaign from the late 70’s quite well. There was a “jingle” that sticks in my mind. “Frozen fish is just as nutritious and tastes as delicious as fresh fish!” I never believed that!

Just found your blog and love the memories. I’m American and lived in Singapore Oct. 75-76 and then Feb. 78-Jan. 87. I was six when we moved there and my brother was two. My mother says the first thing we wanted to do was have a soft drink from a bag! I went to the American school and had that same nightmare-inducing field trip to Haw Par Villa. When I was 17 I had a summer job at the GM plant in Ang Mo Kio. I took the bus from near Pandan Valley to Ang Mo Kio bus interchange and then took a little shuttle to work. My daughter is 11, the same age I was when my mother first let me go with a friend and take a taxi to Orchard Road for lunch and shopping. Or we could walk to Pizza Hut in the other direction and have pizza all by ourselves! We roller skated and swam in the lagoon at Sentosa. We swam in the ocean and played Capture the Flag at Sisters Island. My 10th birthday was at Big Splash and in later years we loved Mitsokushi Gardens (later renamed C n West for whatever reason). Loved the satay man who came by our house that first year and also the bread man in the gray van with his loaves of bread and pound cake. Lots of good times and good memories living in Singapore! Thanks so much for your wonderful blog.

Hi there , may i know if you will be willing to share more about your experience in Singapore during the period of 1975-59? Do pm me at catrinchen1701@gmail.com 🙂 much appreciated help. thanks

Reblogged this on dercong and commented:

super duper awesome post!

Soon there will be a campaign exhorting all Singaporeans to accept the 6.9 population proposal for 2030. Expect a deluge of articles from all the PAP lackeys and bootlickers to flood our 154th ranked media extolling the virtue of PAP’s wonderful plan to drive Singaporeans to extinction and make this country a super crowded and inhospitable place to live in

Pretty in-depth post, nice one! They probably should relaunched the courtesy campaign =)

“Males with long hair will be attended to last”, what was that all about?!

In the late 1960s, long hair, hippie culture, bell bottoms and psychedelic shirts worn by Western music groups began to influence Singaporeans. However, the former Minister for Home Affairs Wong Lin Ken stepped out and claimed that a guy with long hair and hippie-styled appearance gave people an impression that he’s a drug addict.

In 1970, the government began to strongly “discourage” male Singaporeans with long hair. Students were forced to go for haircuts, while immigration officers began to turn away visitors with long hairs and confiscate the passports of affected Singaporeans if they were going aboard.

The definition of “long hair” was finally determined in 1972, and became a government policy officially. Male civil servants who refused to cut their hairs short were sacked. Public who visited various government bodies were attended last in queues if they spotted long hairs.

Groups of long-haired men were rounded up by police. Even popular artistes were barred from entering Singapore, such as Japanese musician Kitaro and British rock band Led Zeppelin. Bee Gees, however, were allowed to perform their concert at the National Theatre in 1972, but they were made to leave immediately after that.

Hard to explain if you didn’t live the era.

Sad isn’t it?

(Source: “Campaign City: Life in Posters” National Library Board Singapore)

Yes 😦

Actually I think the intent of the campaign was good for the nation back then, but the (obviously bad) execution was another matter altogether…

Some posters of the Road Safety Exhibition held at the Queenstown Community Centre in 1974

(Source: National Archives of Singapore)

Any remembers the “eat more bread campaign”, as kids we had fun repeating the slogans. “Eat more bread, you can also have cakes and sandwiches”, something like that. My memory fails me.

The “Anti-Yellow” drive was started way back in 1960. Since then, for more than half a century, PlayBoy magazines never made it to Singapore shores

(Source: Chronicle of Singapore: Fifty Years of Headline News 1959-2009)

Nice blog, I enjoyed reading your blog about the Singapore education system, which is indeed stressful.

I am a patient and dedicated math tutor offering Individual or Group Tuition, to help students learn effectively at their own pace.

Wish you a nice week ahead.

I vaguely recalled one campaign where the govt encouraged S’poreans to eat less rice but eat more wheat. The campaign was called “Eat More Wheat”. They came up with a book of recipes containing all kinds of dishes made with wheat flour. I think it was in the 60s rather than the 70s when it happened. Can anyone remember?

I remember there was a Captain Green (Frog) Song by NEA, but could not find it on the web.

Anyone remember Teamy the Productivity bee? There is even a jingle that goes with it. I think it’s like this- Good better best/ Never let it rest/ Till your good is better/ and your better, best.

I’m amazed I can remember that.

I’ve always remembered that song and now I have it stuck in my head! They played it on TV a lot.

Do you know or does anyone know if it is possible somewhere to buy the posters?

@fathima No, but I think they were on display for some time at the 11th floor at the National Library at Bugis.

good blog!

Hey there! I am a TV producer from Channel NewsAsia. I am producing a TV series called Treasure Hunt, a show about Singapore in various eras – pre-war, all the way till 1980s. Do you know anyone affected by any of the above campaigns? Do email me if you know any! My email add is wangsimin@mediacorp.com.sg

Reblogged this on Tupperware Fantic and commented:

Good Knowledge of the 70/80s Campaigns here in Singapore. So much changes in here within the short period of 20 – 30 years. Now we are truly a metropolis city.

I am glad to have stumbled upon your blog. Interesting how active the government was when it came to its’ citizens wellbeing.

Very interesting… And I think all those campaigns really worked…

Dear readers, After reading your informative blogs, I learned that campaigns are indeed a good tool to educate the masses. Thanks for sharing and understanding and concurrence.

I’m a foreigner who lived in Singapore for 4 1/2 years. The rest seems like to me history, but I’ve seen Singa the Lion when I was in Primary School there(2009-2013), numerous times. XD It’s cute now that I think about it. Also I remember those anti- drug brochures, we would get those every year and those things had little stories in them. Singapore really put in a lot of effort on these.

In Singapore, Chinese Dialects Revive After Decades of Restrictions

26 August 2017

The New York Times

The Tok and Teo families are a model of traditional harmony, with three generations gathered under one roof, enjoying each other’s company over slices of fruit and cups of tea on a Saturday afternoon in Singapore.

There is only one problem: The youngest and oldest generations can barely communicate with each other.

Lavell, 7, speaks fluent English and a smattering of Mandarin Chinese, while her grandmother, Law Ngoh Kiaw, prefers the Hokkien dialect of her ancestors’ home in southeastern China. That leaves grandmother and granddaughter looking together at a doll house on the floor, unable to exchange more than a few words.

“She can’t speak our Hokkien,” Mrs. Law said with a sigh, “and doesn’t really want to speak Mandarin, either.”

This struggle to communicate within families is one of the painful effects of the Singapore government’s large-scale, decades-long effort at linguistic engineering.

Starting with a series of measures in the late 1970s, the leaders of this city-state effectively banned Chinese dialects, the mother tongues of about three-quarters of its citizens, in favor of Mandarin, China’s official language.

A few years later, even Mandarin usage was cut back in favor of the global language of commerce, English.

“Singapore used to be like a linguistic tropical rain forest — overgrown, and a bit chaotic but very vibrant and thriving,” said Tan Dan Feng, a language historian in Singapore. “Now, after decades of pruning and cutting, it’s a garden focused on cash crops: learn English or Mandarin to get ahead and the rest is useless, so we cut it down.”

This linguistic repression, and the consequences for multigenerational families, has led to a widespread sense of resentment — and now a softening in the government’s policy.

For the first time since the late 1970s, a television series was recently broadcast in Hokkien, which in the 1970s was the first language of about 40 percent of Singaporeans. Many young people are also beginning to study dialects on their own, hoping to reconnect with their past, or their grandparents.

And in May, the government endorsed a new multidialect film project, with the minister of education making a personal appearance at the film’s release, unthinkable just a few years ago.

The government’s easing of restrictions amid public discontent makes Singapore something of case study for how people around the world are reacting against the rising cultural homogeneity that comes with globalization.

“I began to realize that Hokkien was my real mother tongue and Mandarin was my stepmother tongue,” said Lee Xuan Jin, 18, who started a Facebook page dedicated to preserving Hokkien. “And I wanted to get to know my real mother.”

For Singapore’s first generation of leaders, those sorts of ideas sounded like sentimentalism.

At the time of the founding of the Republic of Singapore in 1965, it was led by a charismatic and authoritarian prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, who was a self-taught linguist. A product of the English-speaking elite who rarely spoke Chinese dialects, including Mandarin, Mr. Lee held the popular idea, discredited by linguists, that language was a zero-sum game: speaking more of one meant less mastery of another.

In short, he considered dialects a waste of the brain’s finite storage capacity when it should be filled with, above all else, English.

“He felt that since he couldn’t do it, the rest couldn’t do it,” said Prof. Lee Cher Leng, a language historian in the China studies department at the National University of Singapore, referring to Mr. Lee’s inability to fluently speak multiple languages. “He felt it would be too confusing for kids to learn the dialects.”

As the government considered which of Singapore’s many languages to focus on, Mandarin Chinese and English were the logical choices. China, although more than a thousand miles away, was the ancestral homeland of most Singaporeans and was embarking on economic reforms that captivated Mr. Lee. English, the language of Singapore’s elite since the British established a trading port here in 1819, was the dominant global language of culture and commerce.

But neither language had much to do with the people who lived in Singapore when the government launched its policy in the 1970s.

Then, as now, roughly 7 percent of Singaporeans came from southern India and most spoke Tamil. Another 15 percent spoke Malay. The ethnic Chinese, who then as now make up 75 percent of the population, had immigrated over the centuries from several mostly southern Chinese provinces, especially Fujian (where Hokkien is spoken) and Guangdong (home to Cantonese, Teochew, and Hakka). Only 2 percent spoke Mandarin.

Although called “dialects” by the government, some of these Chinese tongues are at least as different as the various Romance languages. The government’s policy was something like ordering Spaniards, French and Italians to abandon the languages they grew up with in favor of Portuguese.

The policy was rolled out in waves. In 1979, the government launched a “Speak Mandarin” campaign. In some schools, pupils who spoke dialects were fined and made to write out hundreds of times, “I will not speak dialects.” The population was bombarded with messages that dialect speakers had no future.

By 1981, television and radio were banned from broadcasting almost all dialect shows, including popular music. That left many people cut off from society.

“Old people suddenly couldn’t understand anything on the radio,” said Lee Hui Min, a writer whose best-known work, “Growing Up in the Era of Lee Kuan Yew,” recounts those decades. “There was a sense of loss.”

Then, in 1987, to foster unity across Singapore’s three major ethnic groups, Chinese, Indian and Malay, English became the main method of instruction in all schools. Today, almost all instruction is in English except for a class in the student’s native tongue: Tamil and Malay for ethnic Indians and Malays, and Mandarin for ethnic Chinese.

The dominance of English was captured in a recent government survey that showed English is the most widely spoken language at home, followed by Mandarin, Malay and Tamil. Only 12 percent of Singaporeans speak a Chinese dialect at home, according to the survey, compared with an estimated 50 percent a generation ago.

“Sometimes people say the Singaporeans aren’t too expressive,” said Kuo Jian Hong, the artistic director of The Theater Practice, an influential theater founded by her father, the pioneering playwright and arts activist Kuo Pao Kun. “I feel this is partly because so many of us lost our mother tongue.”

But as Singapore has prospered, many are searching for their cultural roots, a trend that has picked up since the passing of former Prime Minister Lee in 2015. Some are trying to protect historical monuments, others challenging official versions of history, or passionately defending “Singlish,” a local patois of English, Chinese dialects and Malay.

For some, it means committing to learn their ancestral language.

At the Hokkien Huay Kuan, a community center founded in 1840 to promote education and social welfare among immigrants from Fujian Province, classes have been offered for the past few years in the Hokkien dialect.

One recent Friday evening, about 20 people sat in a small classroom learning phrases like “reunion meal,” “praying for blessings” and “dragon dance.” Three students were doctors specializing in geriatric care who wanted to understand older patients. Others were simply curious.

“I think it’s to understand our roots,” said Ivan Cheung, 34, who works in Singapore’s oil refining industry. “To know our roots you have to know dialect.”

The head of the community center, Perng Peck Seng, said that it, too, had seen the effects of the government policy. When he joined in the 1980s, all meetings were held in Hokkien and Mandarin. Now they are held in English and Mandarin because too few people, even in his organization, speak Hokkien fluently enough to conduct meetings.

But Mr. Perng stopped short of criticizing the government. Instead, he said Singaporeans themselves had to take responsibility for the loss of their language diversity.

“Sometimes I think we are too docile,” Mr. Perng said. “Leaders said if you speak too much dialect it’ll affect your success in life, so many people dropped it on their own accord. The biggest problem is our own consciousness.”

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/26/world/asia/singapore-language-hokkien-mandarin.html

I’m only going to comment about your first line in the “anti-smoking” campaign section. Smoking control, if seriously intended by any country, has several components that must act together : education-awareness, regulation, fiscal measures( tax / price of cigarettes) and help for smokers to stop smoking. Contrary to your first line , the smoking control programme in Singapore was very successful . Check smoking rates over the years, please.

Pingback: Are Dialects Dead? Not Everyone Thinks That Way. – m24307

Great read thaank you