In the late sixties, the Singapore government launched several urban renewal projects at the city and downtown areas. The land between Beach Road and Nicoll Highway, dubbed as the Golden Mile, was one of the options for development. By 1973, a new uniquely-shaped building Woh Hup Complex – better known as Golden Mile Complex – was completed at the site.

The $18-million Woh Hup Complex was often lauded as an architectural wonder – its stepped terraces, designed to increase ventilation and natural light within the building, created a distinctive image of a sloping façade from far and made it a prominent landmark along Beach Road.

The design and development of the complex was mostly carried out by homegrown companies. Singapura Developments, one of Singapore’s major private developers, was awarded with the project, who then hired local architect firm Design Partnership (DP Architects today) and contractor Woh Hup to design and construct the building.

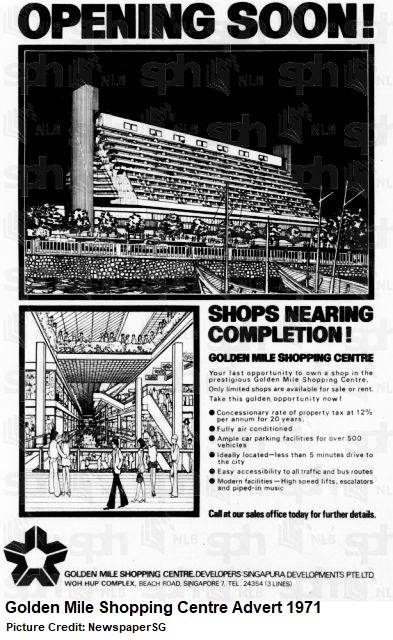

Woh Hup Complex was opened on 28 January 1972, ahead of its completion, by YK Hwang, the managing director of the Industrial and Commercial Bank. At the time of its completion, it was one of the first large-scale mixed developments in Singapore. The 16-storey building was an integration of commercial, recreational and residential uses, where the top seven floors were occupied by residential units, fourth to ninth storeys by offices, and the first to third levels made up of shops that collectively formed the Golden Mile Shopping Centre. These strata-titled retail shops and offices were marketed by the developer in 1971 to attract interested buyers.

In 1974, the 24-storey Golden Mile Tower was opened beside Woh Hup Complex. Its Golden Theatre was once Singapore’s largest cinema with 1,500 seating capacity. The two neighbours shared an underpass that linked the buildings together. Woh Hup Complex became more popularly known as Golden Mile Complex.

The shops at Golden Mile Complex in the seventies and eighties sold a wide range of products, ranging from electrical appliances, cameras and watches to videotapes, jewellery and gym equipment. There were also technical training centres offering courses. One specialised shop, one of the only three in Singapore, offered sporting firearms including airguns, rifles, pistols and revolvers.

This “selling everything under one roof” concept reflected a change in the locals’ shopping habit. Singaporeans could now drive to the complexes, buy all they need in those buildings, and drive away without having to go to another part of the city area.

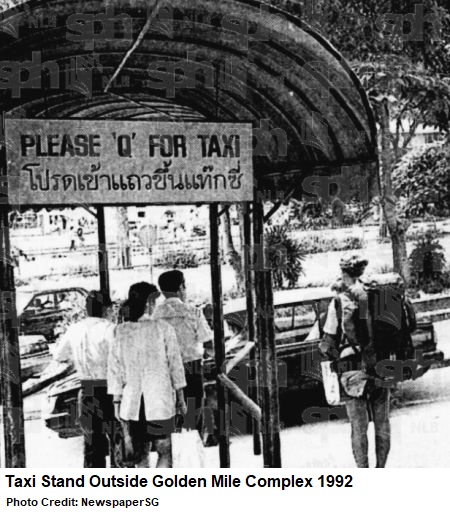

Travel agencies had also moved into Golden Mile Complex; it was a common sight to see Malaysia-bound coaches lining up outside the complex, which in the seventies and eighties also functioned as the unofficial terminal for buses plying the Singapore-Hat Yai (Thailand) route. It would take as much as 18 hours for the buses to travel between the two countries. Thai vendors often brought in newspapers, magazines and other Thai goods to sell at Golden Mile Complex.

Golden Mile Complex’s residential units were also in hot demand as they commanded a great sea view. A typical two-roomed unit at the complex would fetch about $73,000 in 1979.

Golden Mile Complex’s affiliation with Thai cuisine and culture probably began in 1983 when First Thai Siam Snack House, the first and possibly only snack bar in Singapore that offered Thai food, opened at the ground level of the complex. At the same period, the travel agencies at Golden Mile Complex also heavily advertised holiday destinations and affordable air tickets to Bangkok, Pattaya and Hua Hin.

With more and more Thai stalls and shops popped up, food critics praised the dining and shopping experience at Golden Mile Complex as like being at Thailand’s famous bustling Pratunam. By the mid-eighties, Golden Mile Complex was nicknamed the “Little Thailand” or “Little Bangkok”, popularly known for its authentic and reasonably-priced Thai cuisine. It also became a gathering enclave for the Thai residents and workers in Singapore, who felt at home with their familiar Thai music, food and merchandise at the complex. In 1987, there were about 20,000 Thai workers in Singapore, which increased to 50,000 by the mid-nineties.

In the 2000s and 2010s, mookata, a Thai barbeque steamboat, had rapidly garnered a following in Singapore. Golden Mile Complex, over the years, had numerous popular mookata restaurants and eateries occupying the first and second floor of the building.

Golden Mile Complex was plagued by maintenance issues in the eighties, to the extent that 32 angry tenants and proprietors came together in 1983 to submit a petition to the building’s facility management to complain about the frequent water supply disruptions, lift breakdowns, peeling wall paints and defective corridor lights. In 1984, the shopowners and residents had to endure heat and stuffiness for several months after the building’s air-conditioning system broke down.

The toilets at Golden Mile Complex were rated in 1988 as one of the dirtiest and most poorly-maintained toilets in Singapore. In 1991, a fire damaged the building’s generator room, causing a massive power outage for days.

Another issue was the illegal immigrants working and staying at Golden Mile Complex. The immigration officers collaborated with the police to carry out multiple raids at the complex over the years, with one of the largest operations launched in 1989. 370 suspected illegal Thai immigrants were apprehended, where 160 were charged for overstaying, having no documents or having forged work permits. As many as 10,000 illegal Thai workers were sent home under the amended Immigration Act that came into effect on 31 March 1989.

In 1990, a rumour spread like wildfire at the Thai workers’ dormitories and their hangout spots at Golden Mile Complex. In just 10 weeks, 10 young and healthy Thai workers were found to have died in their sleep. It was likely due to the inhaling of the emitted toxic fumes when the workers cooked glutinous rice in PVC pipes.

But many Thais believed it was due to an evil female spirit that took the victims’ life. Some would paint their fingernails and even apply make-ups before going to sleep, so that the ghost would mistaken them as women. A deeper look at these unfortunate incidents revealed the poor and harsh living conditions of these workers. Many had to squeeze into small bunks and resorted to unconventional ways of cooking in order to save money.

By the mid-nineties, the image of Golden Mile Complex swiftly deteriorated in the eye of the public. Rowdy drunkards, frequent brawls, sleazy nightclubs and high-profile stabbing and murder cases were some of the negative impressions portrayed by the place. The complex was also poorly maintained with dirty toilets and stained corridors. Some of the residents patched their balconies with unsightly zinc sheets and wooden boards.

From an architectural marvel in its early days, Golden Mile Complex had become, to some people, an eyesore and was even labelled as a vertical slum by Dr Ivan Png, the Member of Parliament between 2005 and 2006. There were even suggestions to demolish the complex.

After the 2000s, the owners of Golden Mile Complex tried several times to sell the property via en-bloc deals, but without successes. In 2021, Golden Mile Complex was officially gazetted as a conserved building. A year later, with 80% of the strata-titled shop and unit owners agreeing to the deal, the complex was acquired for $700 million by a consortium made up of Far East Organization, Perennial Holdings Private Limited and Sino Land.

The new owners are allowed to rejuvenate the building with incentives offered by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), such as adding a tower of floor area not more than one-third of the existing building and a renewal in its 99-year lease.

Golden Mile Complex shall present its new clean image in a few years’ time. But “Little Thailand”, and all its accompanying memories, good or bad, were gone forever.

Published: 26 May 2023

Discover more from Remember Singapore

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great timely article, RS postings are not taken for granted (roughly one every month but not always) and this reminiscing is well appreciated

I know it is not the remit of this blog but I ask fellow readers to consider the significance of the URA conservation listing in 2021, particularly in comparison to the fate of the old National Library building at Stamford (not forgotten nor forgiven)

I am not an architect nor have particular interest in building design but my wide reading made me aware of the Golden Mile Complex long before they even propose heritage listing.

There are a few international architectural journals and media outlets that had mentioned this building as a prime example of brutalism, megastructures or mixed used arrangements in Asia so it would be interesting to see the next incarnation of this well known structure

I am guessing the new owners will retain some form of mixed use, possibly retail, hotel and service apartments or residential units tied to hotel management

Golden Mile Complex to feature architecture centre after upgrading is completed in Q3 2029

10 December 2024

The Straits Times

When Golden Mile Complex re-opens to the public after its refurbishment is completed in late 2029, visitors can expect to experience familiar “character-defining elements” like the building’s large atriums once again.

Keeping the atriums is one of the reasons behind the decision to build a new 45-storey residential tower to complement the conserved complex, which has been renamed The Golden Mile, said its owners and architects working on the project.

On Dec 10, Far East Organization and Perennial Holdings – the lead developers of a consortium that bought the building in 2022 – unveiled their plans for The Golden Mile, ahead of the launch of its offices and medical suites for sale later in the month.

Golden Mile Complex is the first large-scale strata-titled building to be conserved in Singapore. Its conservation in 2021 came with a package of incentives unique to the complex, to support the commercial viability of reusing it following a collective sale.

The project has been closely watched by built environment professionals as a test case for how large, modernist buildings can be conserved, rejuvenated, and potentially developed upon in a sensitive and profitable manner.

One notable incentive was bonus gross floor area resulting in a one-third increase over the site’s original development intensity, which the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) previously said could lead to a 30-storey residential tower being built alongside the complex.

The consortium was also allowed to purchase some adjoining state land to create a more regular site boundary for the tower.

In August, the URA gave the developers permission to build a 45-storey tower named Aurea – 15 more storeys than what the authority had initially cited – and approval to add four storeys to the conserved complex.

Aurea and The Golden Mile will be part of a mixed-use development known as Golden Mile Singapore, with Aurea’s 188 residential units set to be launched for sale in the first quarter of 2025.

Explaining Aurea’s height in an interview with The Straits Times, Far East Organization executive director of property services Marc Boey said it is a confluence of several factors.

First, the developers purchased less state land than what was offered by URA. Without disclosing the details, Mr Boey said the land bought was “just what was needed to come up with a good development, and a good form and massing for architecture”.

Second, Mr Boey said the developers decided to include an architecture centre in the conserved complex, which Golden Mile Singapore received additional bonus gross floor area for, under the URA’s Community/Sports Facilities Scheme.

Third, retaining the complex’s open atriums meant that the developers could shift bonus gross floor area to other parts of the project, said Mr Seah Chee Huang, chief executive of DP Architects – the firm working on Golden Mile Singapore.

Based on URA’s guidelines and projections, bonus gross floor area could have been added to the complex’s open atriums, such as by “slabbing over”, or adding floors, to the atrium at the retail area in the complex’s lower storeys, Mr Seah said.

But doing so would have affected the atriums, which he said are “character-defining” spatial elements of the building that previous users cherish.

At 22 storeys, The Golden Mile is set to have 156 strata-titled office units across about 37,600 sq m and 19 medical suites totalling 3,000 sq m – each with an ensuite toilet. The complex will also offer about 11,463 sq m of retail space, and have a 2,322 sq m architecture centre.

Six different types of office spaces will be built, with some, such as the crown offices to be housed in the building’s four new storeys, offering panoramic views of the Kallang Basin.

The development will also offer office spaces with private lift lobbies, and loft mezzanine office units with double-volume ceilings by combining some of the complex’s former residential units.

The Golden Mile is on a 99-year lease that began on Nov 18, and its tenants are slated to start moving in from the third quarter of 2029.

A public sky garden will be added to 18th storey, which was the conserved complex’s rooftop.

Mr Seah said the garden will separate the original building and the additional four storeys.

DP Architects decided to “create something that is clearly ‘new versus old’, rather than augment Golden Mile Complex in a way that makes it unrecognisable to the public”, he said.

The design of the additional four storeys was inspired by a sketch by the Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group (Spur), he added.

Spur was an urban planning think-tank active in the 1960s and 1970s, and counted pioneer architects William Lim, Tay Kheng Soon and Koh Seow Chuan among its members. The trio co-founded Design Partnership, which is today DP Architects, and were part of the design team for Golden Mile Complex, which was completed in 1973.

The Spur sketch, which shows a series of high-density megastructures that resemble Golden Mile Complex in form, decorates a wall in DP Architects’ office in Marina Square – one that Mr Seah said the firm’s architects walk by daily.

“We were studying different ways of blending the old and the new, and when we saw it, it was a eureka moment,” he said.

The building’s iconic 9th storey deck, which was formerly used by residents as a recreational space, will be turned into a publicly-accessible sky terrace.

Mr Seah said retaining residential units within the conserved complex would have made it difficult to open The Golden Mile’s gardens for public access, as these would have to be kept for residents’ use.

On the architecture centre, Far East Organization’s Mr Boey said the developers envision that it will complement the URA’s Singapore City Gallery, which showcases urban planning in the country.

“What is more befitting than putting an architecture centre within a conserved building that is also an architectural icon?” he said, adding that plans for the centre are still in their infancy, and that the developers are working with URA and other advisors “to conceive how the centre should be curated”.

In its latter years before Golden Mile Complex closed for refurbishment in May 2023, Golden Mile Complex had housed a sizeable number of Thai businesses, which many came to associate with the building.

Asked if these could make a return, Perennial Holdings chief executive Pua Seck Guan said the Thai businesses are just one chapter of the building’s history, adding that it was the building’s deterioration over time that led to it become a long-distance bus hub, and a Thai enclave.

“When I was younger, it was one of the places you would visit to watch a movie,” said Mr Pua, with Mr Boey adding that memories associated with the building depends on which time period one grew up in.

“Social memories will keep evolving, and it’s not possible to freeze time and go back to something,” said Mr Boey. “Heritage is not stagnant, it will evolve over time or it may run the risk of becoming irrelevant.”

On concerns that the 45-storey Aurea will dwarf the conserved complex, Mr Boey said that instead of focusing on just the conserved complex and the residential tower, most would instead observe the Beach Road skyline as a whole.

“We are actually not that tall relative to some of the buildings along the road,” he said of Aurea.

Reflecting on their experience of purchasing and planning for the refurbishment of Singapore’s first large-scale, strata-titled building to be conserved, Mr Boey and Mr Pua said the journey has been challenging but rewarding.

Mr Pua said it took about two years for the developers to get approval for their plan after purchasing Golden Mile Complex in 2022, adding that there were multiple rounds of negotiations with the authorities before the final design parameters were agreed upon.

He noted that it is not easy to meet conservation guidelines, which have added extra scrutiny on plans for Golden Mile Singapore.

Moving forward, it will take developers who are passionate about conservation work to take on the intricacies of similar projects, as well as bear its significant renovation costs, Mr Pua said. These costs could be higher than developing a new building, he added.

“By retaining the building’s sloping facade and structure, and reintroducing office and retail uses, I think it’s a big achievement,” said Mr Pua. “It will bring life to Beach Road, and in the future even help to enliven the Kampong Glam precinct.”

Golden Mile Complex to feature architecture centre after upgrading is completed in Q3 2029 | The Straits Times