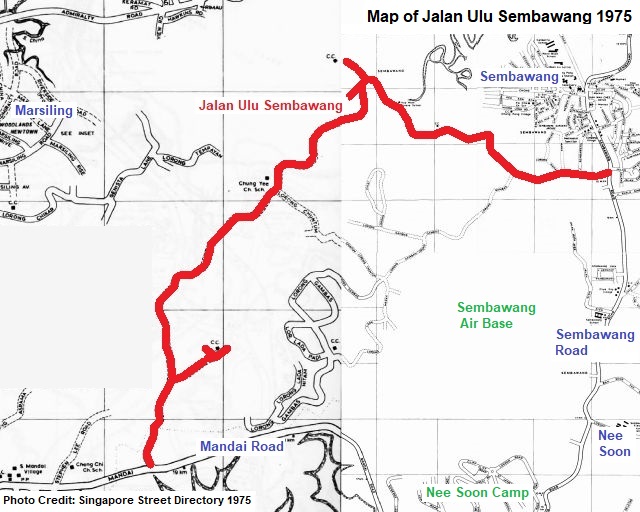

Ulu Sembawang in the eighties remained a rustic, countryside-like place, seemingly isolated from the rest of Singapore that had seen rapid urbanisation over the years. Jalan Ulu Sembawang, the main route in the area, wound through a large part of northern Singapore where it has developed into the new towns of Woodlands, Sembawang and Yishun today.

New Rural Roads

Jalan Ulu Sembawang was one of the nine new roads built in 1948, shortly after the war. It was part of the colonial government’s plans to convert agricultural tracks into better roads in order to better serve the increasing number of residents living at the rural areas of Singapore.

The new roads were Jalan Ulu Seletar, Jalan Kuala Sempang and Jalan Ulu Sembawang in the Sembawang district, and Pepys Road, Yew Siang Road, Jalan Mat Sambol, Jubilee Road, Chua Kay Hai Road and Zehnder Road in the Pasir Panjang area. The naming of these roads, submitted by Sembawang and Pasir Panjang’s village committees, was approved by the Singapore Rural Board.

The Kampong Days

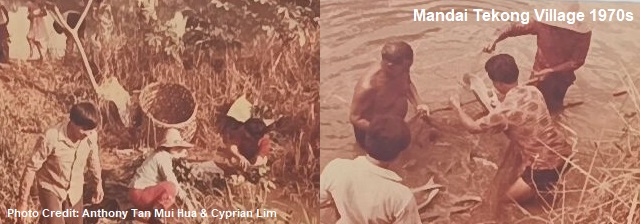

Jalan Ulu Sembawang stretched several kilometres between Mandai Road 12th milestone and Sembawang Road 12th milestone. This vast Ulu Sembawang area had numerous clusters of communities such as Mandai Tekong Village, Mandai Catholic Village, Chong Pang Village, Sungei Simpang Village and other smaller kampongs.

Mandai Tekong Village was named after a company called Mandai Tekong, which owned rubber plantations and other estates at Mandai and Pulau Tekong. The name of Mandai Catholic Village, on the other hand, was associated with the settlement of Catholic Teochew refugees from China.

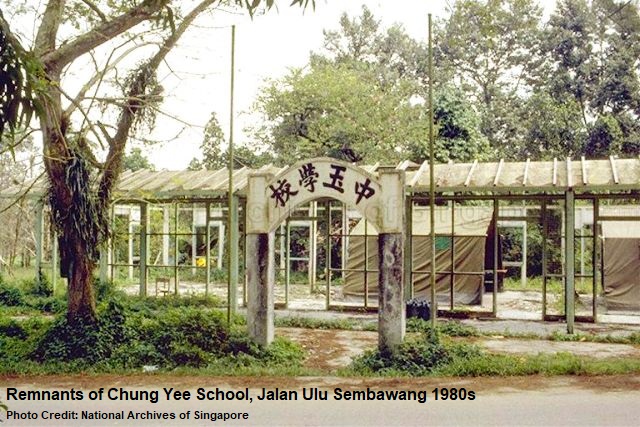

Rural schools were established to support the basic education needs of the villages’ children. The likes of Cheng Chi School, Chung Yee School, Methodist Tamil School, Sin Hwa School and Hua Mien School flourished during the fifties and sixties. The schools’ compounds were often used as makeshift theatres, where free movies were put up by the Ministry of Culture as a form of entertainment for the residents of nearby villages.

Most of the schools were closed by the eighties, after facing diminishing students’ enrollment due to the resettlement of the Ulu Sembawang residents. For example, Hua Mien School’s Primary One student registration, in 1980, had fallen to only 15.

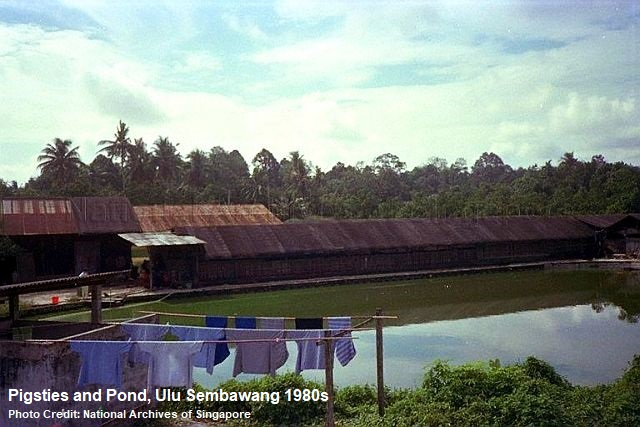

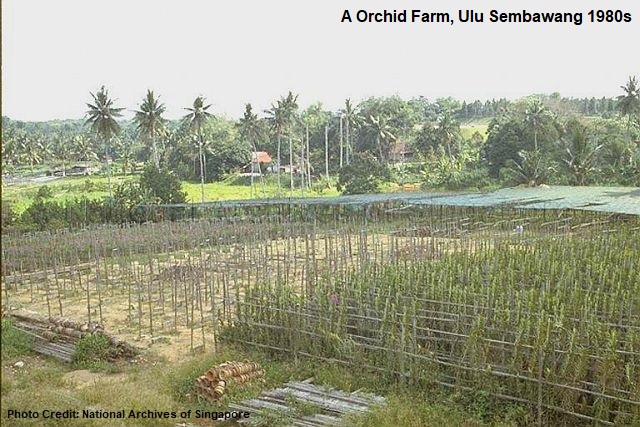

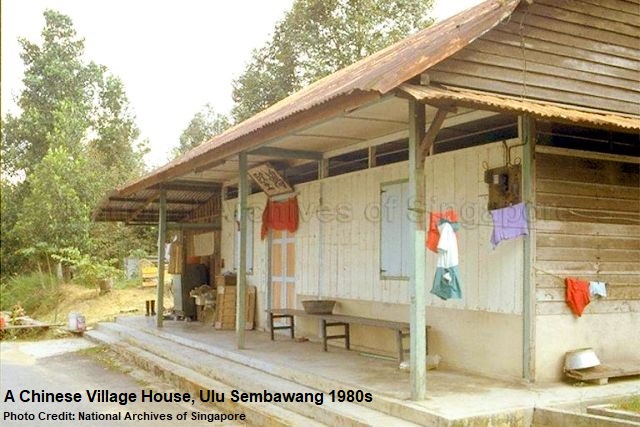

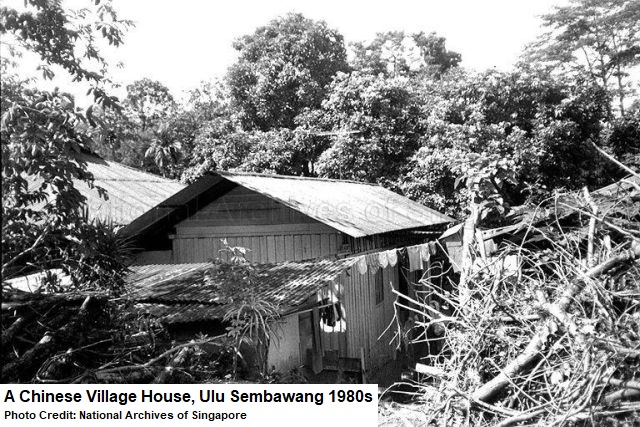

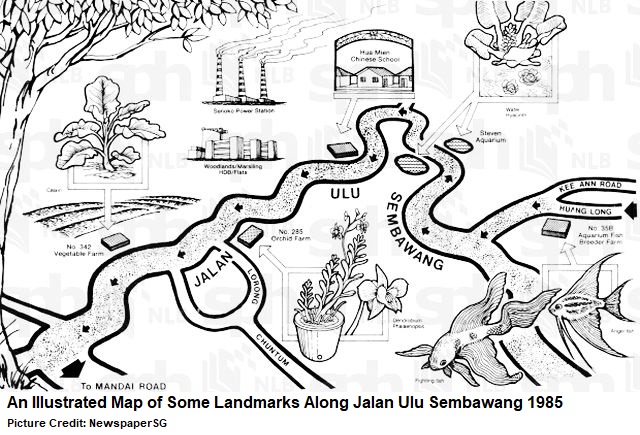

Farmhouses, squatter huts, wells, village schools, fish ponds, pigsties and vegetable farms were still aplenty at Ulu Sembawang, even in the eighties. There were also businesses established in the area, such as car workshops, orchid farms and scrap rubber factories.

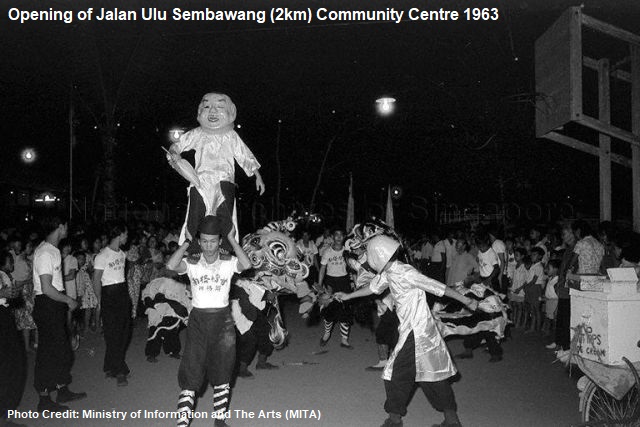

Ulu Sembawang had several community centres too, two of which were the Jalan Ulu Sembawang (2km) Community Centre and Jalan Ulu Sembawang (3km) Community Centre. The “2km” and “3km” probably refer to the distances of the community centres from Mandai Road.

Opened in 1963 by then-National Development Minister Tan Kia Gan, Jalan Ulu Sembawang (2km) Community Centre served the communities for more than 15 years before its closure in 1979. Jalan Ulu Sembawang (3km) Community Centre, on the other hand, lasted until 1985.

Other community centres in the vicinity, including Chong Pang (1960s-1985), Huang Long (1960s-1985) and Canberra (1971-1985), were also closed in the same period. Mandai Tekong Community Centre, located at the junction of Lorong Gambas and Lorong Lada Merah, also ceased to exist in 1985.

Catholic Village

While most Chinese villages in Singapore had traditional religious beliefs in Buddhism, Taoism or other Chinese folk religions, Mandai Catholic Village stood out as a rare one with Catholic roots. It was founded in 1927 by Catholic Teochew refugees fleeing from a chaotic China plagued by political unrest. With no money or ties here in Singapore, they sought help from Father Stephen Lee (1896-1956), the assigned chaplain to the refugees.

Father Stephen Lee made a total of 49 applications to the colonial government, before it was approved that the refugees could settle down at the Ulu Sembawang and Mandai areas. The Catholic village, also known as hong kah sua in Teochew, soon thrived and the government named the village road Stephen Lee Road, in recognition of the chaplain’s effort. The road’s entrance was located near 13 milestone of Mandai Road.

Father Stephen Lee also founded Cheng Chi School for the villagers’ children so they could receive some formal education. The school lasted from 1932 to the eighties.

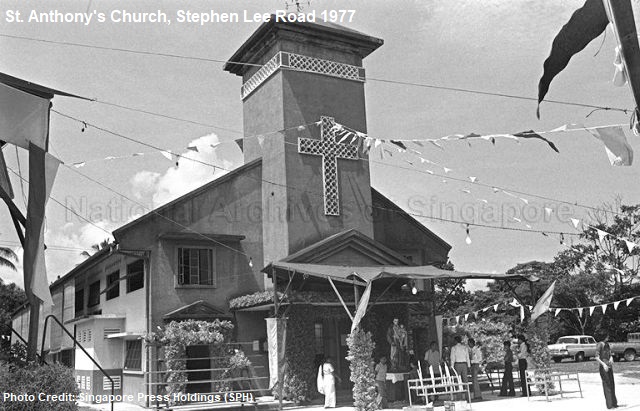

A wooden chapel was constructed in 1933 as a place of worship for the villagers. St Anthony’s Church, a larger concrete building, replaced the chapel in 1960. When the villagers were resettled in the eighties, the church was relocated to Woodlands Avenue 1 in 1994, where it stands till this day.

Network of Roads

Besides the main Jalan Ulu Sembawang, there were numerous minor roads and tracks reaching different parts of Ulu Sembawang. For example, Huang Long Road allowed the residents and drivers to reach Chong Pang Village and Sultan Theatre. Lorong Maha was paved and opened for traffic in 1968. Lorong Gambas lent its name to the modern Gambas Avenue today.

By the nineties, most of these roads were expunged or absorbed into the Singapore Armed Forces’ (SAF) military training grounds. Other than the abovementioned roads, others such as Chong Sin Road, Lorong Pikat, Lorong Chikar, Lorong Chuntum, Lorong Lada Merah and Lorong Lada Padi had all vanished into history. Lorong Lada Hitam is one of the few remaining ones still existing in the area.

Jalan Pasar Sembawang, located on the opposite side of Sembawang Road at 12¾ milestone, had a name similar to Jalan Ulu Sembawang. The difference between the two is that ulu means “remote” or “secluded” in Malay, whereas pasar refers to “market”. Jalan Pasar Sembawang was expunged in the early nineties.

Before 1986, Mandai Road was a narrow two-lane undivided carriageway. That year, the Public Works Department (PWD) began a road widening project to convert it into a three-lane carriageway with a central divider. It took four years for the completion of the road project that included the improvement works to the street lights, bus bays, footpaths and drains along Mandai Road.

Gotong Royong

Before the seventies, Jalan Ulu Sembawang was nothing more than a dirt track. Some sections of the road were in such bad conditions that Teong Eng Siong, Member of Parliament (MP) for Sembawang, brought it up in the parliament in the early seventies, asking if the road could be repaired immediately.

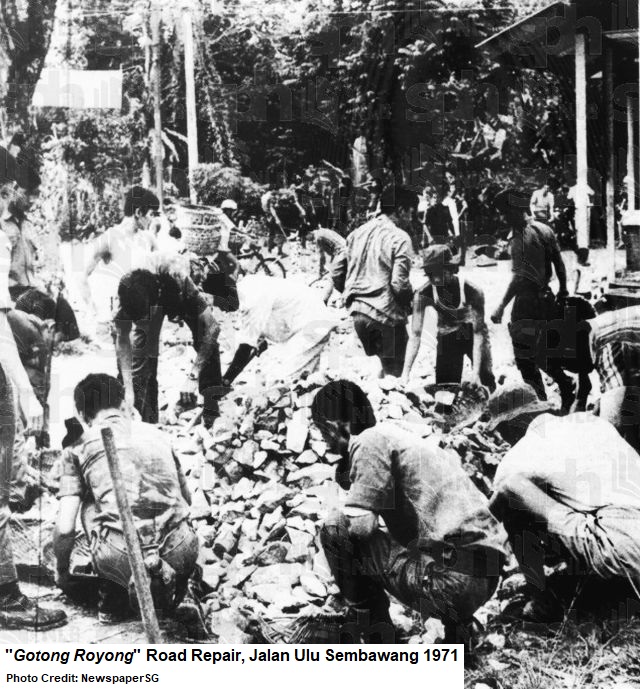

Hence in 1971, about 130 national servicemen from Seletar West Camp and 50 residents volunteered, in the good spirit of gotong royong (“communal work”), to repair a 1.7km damaged stretch of Jalan Ulu Sembawang. The machines, tools, materials and technical knowledge on road construction were supplied by the PWD.

It took just four days for the volunteers to complete the road repair project. Costing $65,000, the newly repaired stretch was officially opened by Teong Eng Siong on 6 March 1972, and was expected to benefit 8,500 residents living at the Bukit Panjang, Nee Soon and Sembawang areas.

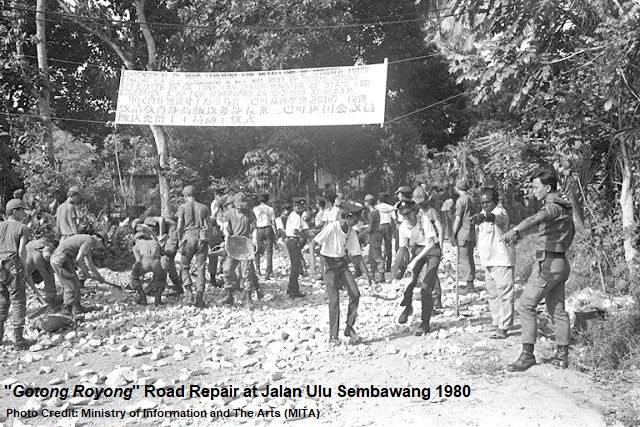

In 1974, another gotong royong road repair project saw 300 residents and 1,200 Singapore Polytechnics students taking part in the metalling of a 2.75km-long section of Jalan Ulu Sembawang.

Another gotong royong work in 1978 had 900 volunteers, including Mandai Camp I and Nee Soon Camp’s national servicemen as well as students from Chung Yee School and Hua Mien School. Together, they laid a 1.1km-long track at Jalan Ulu Sembawang that served as a shortcut between Mandai Road and Sembawang Road. The completion of the track improved the accessibility to the area where there were about 100 houses, two schools and a community centre.

Illegal Activities

Despite the tranquility of Ulu Sembawang, it, however, possessed a darker side. Due to its secluded nature, the area was also notorious for being a popular hideout place for secret society members, robbers and kidnappers.

In 1954, under “Operation Eagle”, the Singapore Police’s Special Branch and Reserve Unit raided several Jalan Ulu Sembawang farmhouses, arresting five Malayan Communist Party members and unearthing arms caches of pistols, live rounds and grenades.

Throughout the sixties and seventies, there were cases where illegal samsu and opium manufacturers were caught at Ulu Sembawang. For example, in 1973, the Customs and Excise Department successfully busted two illicit samsu distillers hidden in an old rubber estate along Jalan Ulu Sembawang.

In 1974, the police stormed a gangster hideout at Jalan Ulu Sembawang and arrested six Gi Leng Hor 18 secret society members. A cache of gangland weapons such as parangs, daggers, bearing scrapers and iron pipes were seized by the police. Gi Leng Hor 18 was also suspected to be involved in the murder of a 24-year-old labourer at Jalan Ulu Sembawang in 1973. Another secret society that actively operated at Ulu Sembawang was Ang Soon Tong.

Jalan Ulu Sembawang, together with Jalan Kemuning, hit the headlines again in 1974 when it was revealed that both places had brothels and gambling dens disguised as exclusive clubs for foreign sailors. Some local taxi drivers earned their commissions by fetching the foreigners to these “popular clubs”.

In 1992, the Singapore Police busted an illegal cockfighting arena at Jalan Ulu Sembawang, where some disused kampong huts were converted for the betting game that was banned in Singapore since the sixties. Attracting more than 100 Singaporeans and Malaysians to visit every weekend, the betting stakes for the cockfighting were between $30 and $500 per fight, but some bets reportedly could rise to as high as $5,000.

Mysterious Case

A mysterious case occurred at Ulu Sembawang in 1991. A 38-year-old woman Cheah Moi Moi went missing with her truck found abandoned along a deserted stretch of Jalan Ulu Sembawang.

Cheah Moi Moi was the owner of a mobile grocery business that supplied vegetables, fish, eggs and rice to the foreign workers at the construction sites. On 4 March 1991, she was reported missing by her 26-year-old business partner Lim Keow Soon when he found her truck along Jalan Ulu Sembawang. The police combed the area but found no traces of the missing woman and any signs of struggle.

Cheah Moi Moi was last seen by her sister-in-law at the Chong Pang Market on 3 March. She was never found and her case remains unsolved till this day.

Amenities and Landmarks

A $1.5-million telephone exchange was built by the Telecommunications Authority of Singapore (TAS) in 1975 at the junction of Jalan Ulu Sembawang and Sembawang Road. Another $2.1-million telephone exchange was built at Telok Blangah Way.

Both exchanges allowed TAS to add 12,000 telephone lines to its system, with a potential to increase another 40,000 lines, to serve the increasing number of residential and commercial telephone users in Singapore.

The Jalan Ulu Sembawang telephone exchange site was acquired in 2002 for $17 million by Centrepoint Properties Ltd, formerly known as Frasers Centrepoint Singapore, to be used for private residential redevelopment.

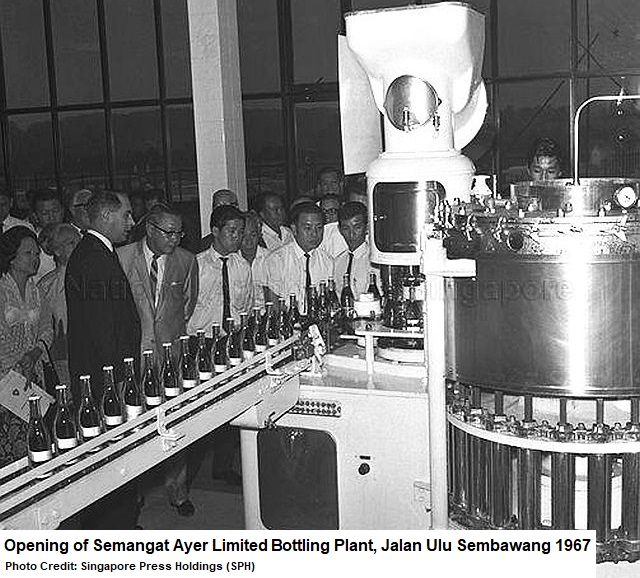

Another landmark near the junction of Jalan Ulu Sembawang and Sembawang Road was Fraser & Neave’s (F&N) $1.5-million bottling plant called Semangat Ayer Limited. Opened in 1967, it bottled Seletaris, a popular mineral water brand made from the Sembawang Hot Spring. Its site was acquired in 1985 by the Ministry of Defence to become part of Sembawang Air Base, but the hot spring was released back to the public in the nineties for recreational use.

Bus Services

Public bus services arrived at Ulu Sembawang in July 1978. Despite its great length, Jalan Ulu Sembawang was not served by any public buses prior to this year. The only form of public transport was a few taxis willing to ply the route, and their relatively expensive fares meant that many Ulu Sembawang residents would rather walk almost an hour or cycle long distances to reach their homes from the main Mandai or Sembawang Roads.

In the late seventies, the Registry of Vehicles (ROV) introduced Scheme B bus services to the rural areas of Singapore to provide better accessibility and convenience to the residents. The buses, charging 20c for a 3km ride, 30c between 3km and 6km, and 40c for distances more than 6km, were able to pick up and drop off passengers anywhere along Jalan Ulu Sembawang. Students were charged a flat rate of 10c.

Land Acquistions and Resettlement

By 1983, there were only 30 small chicken farms and 20 duck farms left at Lorong Gambas, off Jalan Ulu Sembawang. The larger poultry farms had been relocated to Lim Chu Kang, whereas the remaining ones were given eviction notices by the government.

In the sixties, Bukit Sembawang Estates, one of Singapore’s largest landowners and property developers, had acquired large parts of the Ulu Sembawang area. Some of the lands were cultivated into rubber plantations, managed by the company’s subsidiary Singapore United Rubber Plantations. Other parts were designated for agricultural and rural purposes.

Over the years, the company had sold much of its rubber plantations and lands at Jalan Kayu, Sembawang, Nee Soon, Pasir Ris and Punggol to the Singapore Government for residential redevelopment. For Ulu Sembawang, the government acquired almost 550,000 square metres of the lands from Bukit Sembawang Estates in 1985.

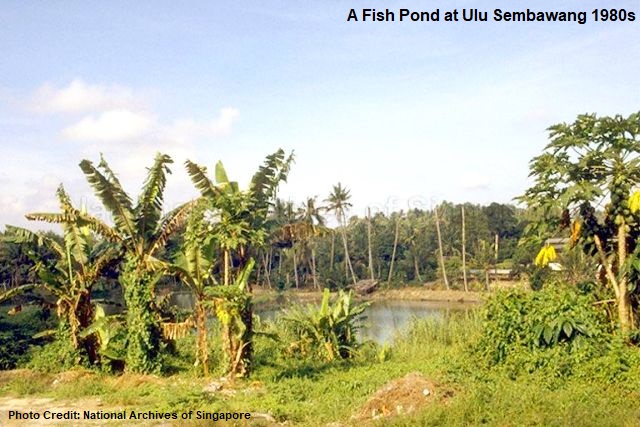

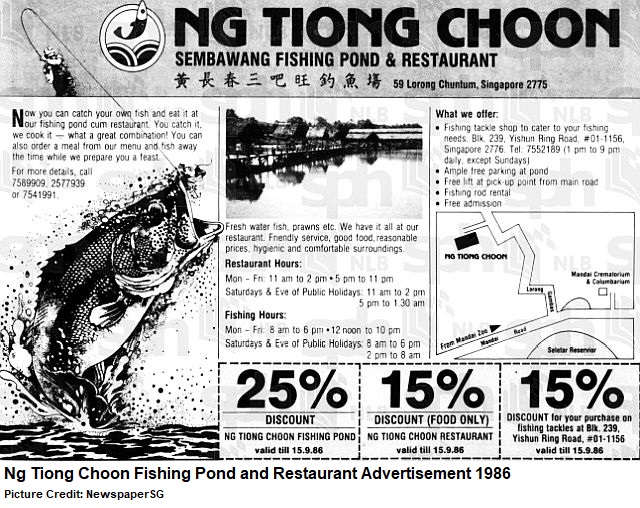

Old-time fishing enthusiasts might remember the large pond at Lorong Chuntum, off Jalan Ulu Sembawang, in the mid-eighties, where it was filled with grass carp, snakehead fish and Thai catfish. It had a restaurant called Ng Tiong Choon Seafood Restaurant, where the anglers could engage the chefs, for a price of $10, to cook the fish they caught from the pond.

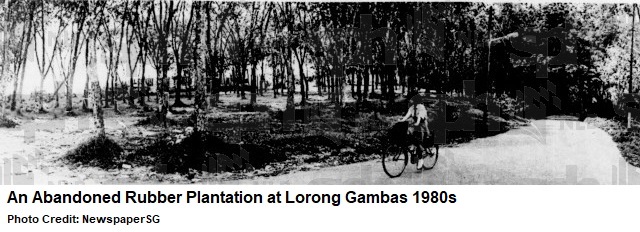

Ulu Sembawang still had rubber plantations in the mid-eighties. One particular rubber plantation, at the junction of Jalan Ulu Sembawang and Lorong Gambas, was known as chiew ni kah, or “foot of rubber trees” in Hokkien, among the residents. In 1987, it was acquired by the government to be used as part of the SAF training ground and camping site for the National Cadet Corps (NCC) and Girl Guides.

Ulu Sembawang’s residents, from 1981 to 1990, were gradually resettled at the new towns of Woodlands, Marsiling, Sembawang and Yishun. By 1984, the SAF began to conduct exercises at the Ulu Sembawang area. For the remaining residents still living at the area, it became a norm for them to occasionally hear the sounds of thunderflashes and firing of blanks.

Some residents, unable to adjust to the flat-dwelling HDB lifestyle, still returned to Ulu Sembawang regularly despite the presence of SAF warning signages. The older residents would often reminisce their tough yet happy days living in the rural areas. Others recalled spending their carefree childhood days climbing trees, plucking fruits and jumping into the ponds and rivers.

By the nineties, the abandoned vegetable farms, empty fish ponds and deserted rubber plantations were reclaimed by nature.

Old Cemetery and Temple

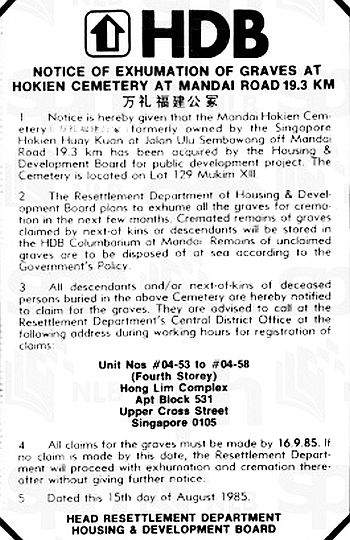

The Mandai Hokkien Cemetery at Jalan Ulu Sembawang was also acquired in 1985 by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) for public housing redevelopment. The 1.6-hectare Chinese cemetery, owned by the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, had more than 20,000 graves, many of where were reinterred in the sixties from exhumed graves at Red Hill and Leng Kee Road’s cemeteries.

The Mandai Hokkien Cemetery at Jalan Ulu Sembawang was also acquired in 1985 by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) for public housing redevelopment. The 1.6-hectare Chinese cemetery, owned by the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, had more than 20,000 graves, many of where were reinterred in the sixties from exhumed graves at Red Hill and Leng Kee Road’s cemeteries.

HDB carried out the exhumation of Mandai Hokkien Cemetery in March 1986, with the first phase involving some 5,200 graves. Mandai Hokkien Cemetery’s unclaimed remains, together with the unclaimed remains of other exhumed cemeteries in Singapore, were subsequently exhumed and disposed at the sea off Punggol Point in 1988.

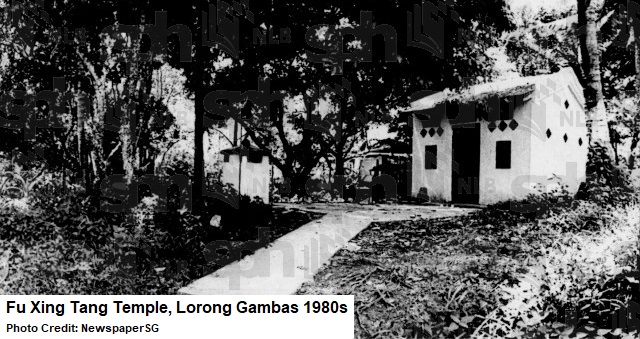

A small Taoist temple called Fu Xing Tang stood along Lorong Gambas. It was built in the fifties by the residents pooling their resources for a place of worship where they could seek peace and protection from Chinese deity Tua Pek Kong.

Like the huts, farms and ponds of Ulu Sembawang, the temple eventually walked into history when the areas were acquired by the government and the residents resettled.

New Park Connector

In 2002, the government looked into the possibility of carving out an area within the SAF training grounds to build a park, allowing the public to access the areas’ rich flora and fauna. Pulau Tekong and Ulu Sembawang were two of the areas studied.

A 1.3km-long Ulu Sembawang Park Connector was constructed and opened in 2010. It was built on a former section of Jalan Ulu Sembawang near its junction with Mandai Road. The rest of the Ulu Sembawang area remains a restricted military ground under the charge of the Ministry of Defence.

Published: 30 November 2024

Updated: 2 December 2024

Discover more from Remember Singapore

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Ulu in the name Ulu Sembawang is a reference to a river. Specifically, the area is upstream of the Sembawang River or Sungei Sembawang. Same for Ulu Seletar and Ulu Pandan.

I would also note how the gov seems to have tricked people then into thinking Ulu Sembawang would be used for public housing, but most of it became military training areas instead. Same for Yio Chu Kang. My family mentioned that was the expectation when they were evicted back then. Only to see their old hometown as a forest.

I didn’t know that distinction. So Ulu in this sense would mean “upstream”?

I walked at that Park Connector and it is longer than 1.3 metres. 🙂

Thanks for pointing out the error. Have amended to 1.3km

Is there where Canberra Road used to be? My secondary school (Naval Base) used to be there but I’ve never studied in the old building. All I remember is a labyrinth of kampong houses in the area.