Kusu, St John’s and Lazarus Islands belong to collective group known as the Southern Islands that is currently taken care by the Sentosa Development Corporation. The other islands under their charge are Sentosa, Pulau Seringat, Sisters’ Islands (Pulau Subar Laut and Pulau Subar Darat) and Pulau Tekukor (also known as Pulau Penyabong or Turtle Dove).

Other than private charters, there is only one ferry service, provided by the Singapore Island Cruise, to fetch the visitors from Marina South Pier to the Kusu and St John’s Islands.

Kusu Island

Located about 5.6km south-western of Singapore, Kusu Island is a small island with many variations in its name. Originally called Pulau Sakijang Pelepah, it is also known as Peak Island, Pulau Kusu, Pulau Tembakul, Goa Island as well as “Tortoise Island”.

Kusu Island’s Places of Worship

Records show that as early as the 1870s, Kusu Island was already famous in the region for its “holiness”. And pilgrims had been visiting the island at the start of the 19th century, even before the arrival of Sir Stamford Raffles.

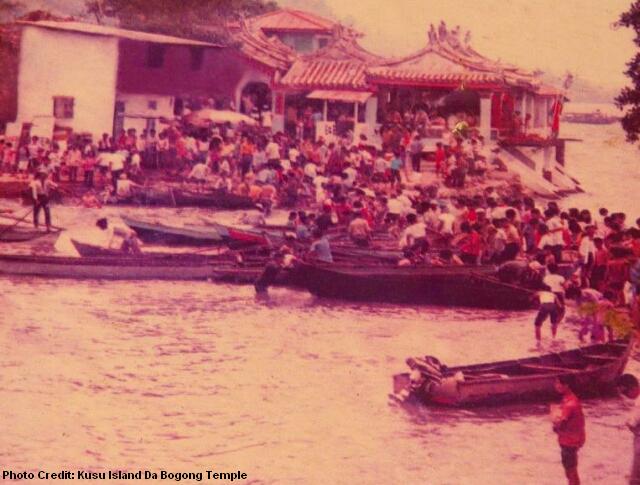

In 1923, a wealthy businessman called Chia Cheng Ho built a Taoist temple to dedicate to Tua Pek Kong (or Da Bogong 大伯公), also known as the God of Prosperity to the Chinese, and Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. By the 1930s, in every ninth month of the Chinese calender, thousands of people would flock to the sacred island for their annual pilgrimage trips, taking sampans and motor boats from the congested Johnston’s Pier.

Arriving at the Tua Pek Kong Temple, the devotees quickly laid out their offerings of candles, joss sticks and money, fruits and “nasi kunyet“, a type of home-made yellow rice, for the gods. In return, they prayed for good health, wealth and safety. A yellow string, to be worn around the wrist, would be given by the shrine to the devotees as a preventive against accidents and evil spirits. Sometimes, flowers were purchased to be used for bathing, so that sins and misfortune can be washed away.

The Malay Kramats (holy shrines) were built at the top of a small hill in the early 20th century to commemorate a pious family – Dato Syed Abdul Rahman, his mother Nenek Ghalib and his sister Puteri Fatimah Shariffah. According to the tradition, a pilgrim had to climb 152 steps to reach the Kramats. It was said that if he could not complete the journey, he would be considered impure in his heart. Devotees would usually pray for five blessings, namely wealth, marriage, fertility, good health and harmony.

Outside the shrine, numerous stones were hanged on the trees and fences; they represented the vows by the devotees, which would be taken off each year after their pledges were fulfilled. Many devotees still practice this tradition today.

The Legends of Kusu

There were many fascinating legends about Kusu Island; one legend tells how a giant tortoise miraculously turned into an island to help a group of drowning fishermen.

Another one was the sworn brotherhood between a Chinese and Malay fisherman after their death. The Chinese fisherman had suffered a fit during a fishing trip and, after his death, was buried at the southern part of Kusu Island by his friends. A tombstone was erected in remembrance of dead fisherman, who was well-liked for his generosity and willingness to help others. The fishermen believed the dead spirit of their friend would continue to help them and other travellers out in the seas, looking after and protecting their safety.

As for the Malay Kramat shrine, the legend began when the Malay fisherman became the Kramat of Kusu after he was the first Malay to be buried on the island. One night, all the Malay and Chinese fishermen in the village had the same dream. In their dreams, the two dead fishermen who were buried on the island had become sworn brothers, and their relatives and friends were to visit Kusu once a year to pay respect.

Another legend, a lesser known one, was about the gods of the Tanjong Pagar hill who travelled across the waters to Kusu. Many years ago, the hill that stood opposite of the Tanjong Pagar Police Station had been slated for development. However, due to the difficulties faced during the leveling of the hill, it was decided that dynamites would be used to break up the hill. That night, five Arabs were spotted taking a sampan to Kusu.

Before arriving at the island, the passengers vanished, leaving the sampan man shocked and bewildered. The only explanation he could come up with was that the five passengers were the gods of the hill. The legend spread and was favourably received by the public, adding an even “holier” touch to Kusu.

“Grand Old Lady of Kusu Island”

A popular and famous temple caretaker used to live at Kusu Island for as long as 80 years. Ng Chai Hoong, also fondly known as “Bibi”, moved to Kusu from mainland Singapore in around 1870. The Tua Pek Kong Temple then was still a small ramshackle hut. She and her husband See Hong Yew took care of the matters in the temple until the mid of the 20th century.

Ng Chai Hoong passed away in 1950 at a ripe old age of 100. She was buried at the slope of the hillock opposite her home at Kusu. Years after her passing, devotees still visited her grave to pay homage.

Development of Kusu Island

In the 1960s, tens of thousands visited Kusu each year. Owners of the tongkangs, charging $2 per head for a two-way trip to the island, were reported to have earned a total of $25,000 in the month of pilgrimage. Hawkers selling food, joss sticks and candles also made their way to Kusu to enjoy a brisk business. With increasing crowds every year, the then-Marine Department in 1965 ruled that, for public safety, permits would be required for boats ferrying the people on pilgrimage trips to Kusu.

In September 1972, the Sentosa Development Corporation was established to oversee the development of Pulau Belakang Mati (today’s Sentosa) into a holiday resort. The statutory board was also tasked to manage other southern islands, including Kusu and Saint John’s Islands.

The 1.2-hectare Kusu Island was reclaimed and merged with another tiny coral island in 1975, a project undertaken by the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA), to become the current size of 8.5 hectares (about 12 football fields). The strip of sand that used to be under the waters during high tides, separating the Chinese temple and the Malay Kramats, was covered.

The 1.2-hectare Kusu Island was reclaimed and merged with another tiny coral island in 1975, a project undertaken by the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA), to become the current size of 8.5 hectares (about 12 football fields). The strip of sand that used to be under the waters during high tides, separating the Chinese temple and the Malay Kramats, was covered.

Ferry services were also started in the same year, taking visitors to Kusu from Clifford Pier and the former World Trade Centre Ferry Terminal. Amenities such as public toilets, lagoons and a hawker centre were built (vacated today except during the period of pilgrimage).

By the late 1970s, Kusu Island had become the second most popular island, after Sentosa, in the Southern Islands group. An estimated 235,000 visited the island in 1979, although a large portion of the visitors were pilgrims. The Sentosa Development Corporation was keen to attract more people to visit the island for picnics and enjoy its idyllic scenery by the lagoons.

St John’s Island

St John’s Island’s original name was Pulau Sekijang Bendera which means “Island of One Barking Deer and Flags”. The island had a significant history, where it was used as a quarantine station, detention centre and rehabilitation centre in the 100 years between 1870s and 1970s.

Famous Lazaretto

Records show that St John’s Island was designated as a quarantine station as early as the 1870s. In 1873, a cholera epidemic took away 357 lives in Singapore. A year later, Qing China suffered a serious plague outbreak. Due to the massive arrival of Chinese immigrants, a plague hospital was built at St John’s Island, and thorough inspections of ships coming to Singapore were carried out.

More than $300,000 were spent on the development of St John’s Island Quarantine Station since 1903, and as many as eight million people were inspected in the following twenty years.

In the early 20th century, St John Island also had its police station, located in front of the long jetty, with a Sikh force of one corporal and twenty men. Equipped with water tanks, pipelines, condensing house and rain water-retention facilities, the island was self-sufficient in the fresh water supplies. Staff quarters, steam boiler houses, storerooms and patient wards were built within the vicinity of the camp.

The oldest building on the island was the Superintendent’s sea-facing bungalow. It was constructed in 1894, at the time when China suffered the serious plague outbreak. The single-storey Tudor-styled bungalow is still standing today, although it is in a derelict state after being abandoned for many years.

By the 1920s, the quarantine station was one of the largest in the world, with sufficient accommodation for 6,000 people at the same time. Each year, the island’s two launches, named Hygeia and Crow, carried out disinfection of some 2,000 ships.

A Penal Settlement

St John’s Island was converted into a detention centre in the fifties, after the gradual slowdown of large-scaled immigration. As a detention centre, it housed many political prisoners and secret society members and leaders. After the mid-fifties, the facilities were converted into a rehabilitation centre for drug users and opium addicts.

Along with Kusu Island and other Southern Islands, St John’s Island was taken over by the Sentosa Development Corporation in the seventies. The drug rehabilitation centre was shut down in 1975, and over the years, the island was redeveloped into a resort that is popular with campers and students today.

Lazarus Island

Lazarus Island is located next to St John’s Island. The two islands are now linked together by a paved bund. Lazarus Island has a former name that was similar to St John’s Island’s. It was known as Pulau Sekijang Pelepah, which means “Island of One Barking Deer and Palms”.

The Island’s Past

There used to exist several convict prison confinement sheds on Lazarus Island in the late 19th century. The sheds were left abandoned after a prisoner, who was sentenced to life imprisonment on the island, made a successful escape. In 1902, a fire destroyed all the remaining sheds. The island was caught in another major fire in 1914, where almost all its vegetation was burnt down.

Like Kusu Island, Lazarus Island had numerous graves of those who had succumbed to various infectious diseases on the nearby St John’s Island. For a period of time, the island was forbidden ground to the public. Others were Muslim tombstones of the former villagers on the island. Today, the graves no longer exist as most of them had been exhumed in the late nineties.

In the sixties, Lazarus Island was used as a radar base fitted with a light-mast and high-frequency omni-directional range equipment for civil aviation. The equipment generated signals that could reach a distance of 200 miles, where they would be picked up by aircrafts coming into Singapore. The pilots could then accurately guide their planes along the selected tracks, thus ensuring the safety of all aircrafts. A Master Attendant used to be stationed on the island, taking care of the daily operational tasks.

The “Dollar” Islands

By the seventies, Lazarus Island, along with other Southern Islands, were taken over by the Sentosa Development Corporation. In 1976, some $11 million was spent on the land reclamation of Lazarus Island, Buran Darat and Pulau Renggit. Lazarus Island was earmarked for recreation development, with swimming lagoons, a family holiday camp, game courts, boatels and scuba-diving facilities proposed.

Pulau Renggit was also called Pulau Ringgit. In the early 20th century, some ninety Malay fishermen and a Chinese storekeeper had lived on the island. Their annual rent was a nominal dollar, which gave rise to the name of the island. Pulau Ringgit Kechil was another island forty yards away. Surrounded by a reef, it was a tiny coral isle with less than a dozen trees. Both were eventually absorbed as part of the enlarged Lazarus Island.

“Children of the Sea”

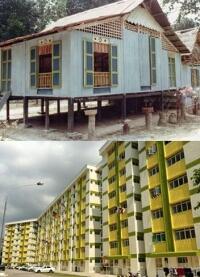

Lazarus Island had several Malay villages in the sixties and seventies. In 1963, the villagers welcomed former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew when he visited the island in his Southern Island Tour.

Lazarus Island had several Malay villages in the sixties and seventies. In 1963, the villagers welcomed former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew when he visited the island in his Southern Island Tour.

There was even a Pulau Sekijiang Pelepah Malay School, which created a sensational headline in 1970 when they won a host of trophies and smashed many records in the Radin Mas District Primary Schools swimming tournament.

Dubbed as “the Children of the Sea”, the participants were said to have trained in the rough waters around Lazarus Island for two months before the competition.

Development of the Island

By the eighties, Lazarus Island was almost emptied, with most islanders relocated to mainland Singapore. In 1988, the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (STPB) invited interested parties to submit proposals to develop Lazarus Island as a beach resort. The development plans, however, never materialised.

Published: 27 November 2014

I’ve only been to Singapore once, June 2013 for only two days. As I was strolling around this city state, I wasn’t too impressed with the places I visited cause i thought it was only malls after malls like every other Indonesians coming to Singapore *yeah right, whaddya expect from a 2 days stay*. So when I returned to Indonesia I decided to do some research and readings on Singapore, and I bumped into this outstanding site because in fact I’m more interested in the history of an (now) urban city state than because Singapore has a long history and it is way more interesting than traveling to the malls.

So for my next visit, I’d use this blog which I’ve read for the past year and always excitedly waiting for updates as a reference for my places-to-go, off the beaten path.

Keep posting, nice to know you.

PS: Nowadays urban place would surely have a long history of a cultural areas, like my city, Bandung, and I know too well how places have evolved and sometimes it just suck. 😀

Good read 🙂

pretty.

Datuk Gong: The god of the Chinese, Indians and Malays

04 December 2015

Yahoo Singapore

Visitors to the Jiu Tiao Qiao Xin Ba Na Du Tan in Tampines Link will notice a shrine to a somewhat unusual figure. It is a bearded Malay man – or is he Chinese? – sitting cross-legged, dressed in robes and a songkok.

Before and around him are baju kurung melayu, songkoks, a stone keris and stone turtles, a symbol of fertility and vitality in Chinese culture. Beside him are two flowing streams of water, as well as ornaments declaring ‘Selamat Hari Raya Aidilfriti’ (Happy Eid).

His name is Datuk Gong, or Nah Tuk Kong. He is a guardian spirit and an earth deity who has taken various forms across different periods and places across Southeast Asia, attracting devotees of different ethnicities and faiths. Mr Tok, 56, caretaker of the Tampines temple, says he has seen Chinese, Indians and Malays coming to pay their respects to the deity.

“All gods are the same. We will all ask for the same things: peace, and that things will go smoothly for us. It’s all the same,” says Tok matter-of-factly.

The origins of Datuk Gong

Malaysian documentary photographer Mahen Bala is the man behind the recent feature documentary Datuk Gong: Spirit of the Land. He explains, “The Datuk is revered as a living spirit, and therefore he is treated with great respect by the community in which he resides. A shrine is built in his name, various offerings are presented and spirit mediums are engaged to communicate with him.”

The shrine may take the form of an idol bearing the likeness of the Datuk – whose features vary across different places -, a tablet with his title inscribed on it or even a rock.

“The majority of old shrines in Georgetown, Penang are dedicated to multiple idols, collectively referred to as beradik or brothers, in multiples of three, five and sometimes seven. They are also represented by a series of coloured flags. However, in Klang, Selangor, most of the idols are dressed up as if they were members of the royal family, complete with headgear, keris and in some cases, accompanied by the entire royal court,” says Mahen.

Master Chong Weiyi, secretary general of the Taoist Federation (Singapore) Youth Group, says the Malay figure in a songkok is very similar to the Chinese earth deity Tua Pek Kong. “It started from the early Straits Chinese immigrants. They will usually ask him for protection and blessing, especially in business,” says Master Chong.

“It reflected the aspirations of the early Chinese immigrants: they wanted to work hard, earn money and go home to China. It gave them the strength to look forward to a better tomorrow. It is also a way for the Malay and Chinese communities to respect each other.”

While the exact number of devotees in Singapore is unknown, Chong says the cult of Datuk Gong was popular in the 1960s and 70s, and is still practiced by the older generation. Besides shrines in Tampines, Loyang Tua Pek Kong and Pulau Ubin, he is also venerated in many factories. “I think they want good business, so they want to be in harmony with the spiritual world,” says Chong.

In a reflection of the mixture of beliefs, devotees offering prayers to Datuk Gong must abstain from pork and alcohol for the day, while offerings to the deity will also exclude these two. Chong says, “Since Nah Tuk Kong is Malay, whatever the Malays don’t like, they won’t do.”

But according to Bala, the cult of Datuk Gong goes backs even further than the early Chinese immigrants. He says, “Having arrived in a foreign land as immigrants, they merely adopted a pre-existing practise. Unlike most organized religions which relied on the teachings of a prophet, saint or holy scripture, the worship of the Datuk is a practise that adapts itself according to the times.”

The cult of Datuk Gong reflects a phenomenon called religious syncretism, or the blending of two or more religious belief systems into a new system. Sometimes, it involves the incorporation into a religious tradition of beliefs from unrelated traditions.

According to Assistant Professor Indira Arumugam of the National University of Singapore’s sociology department, syncretisim is what defines culture, of which religion is a part. She says, “It is entirely natural that religions are influenced by, react to, borrow from and mimic each other – producing interesting hybrids in the process. This is how religions are formed, grow and change. They do not arrive fully formed from nothing but develop in constant exchanges with historical and existing examples.

It is the attempt to purify – to deny their multiple sources and cross-cultural influences that lies at the heart of religious intolerance. What is problematic is the refusal to accord other religions equal validity in order to assert the singular superiority of one’s own.”

The Datok Kong of Kusu Island

Early on a Sunday morning, pest controller Wong Kim Sing, 33, is on a ferry to Kusu Island. He bears joss sticks, as well as offerings of oranges and pineapples. The worship of Datuk Gong runs deep in Wong’s family – back home in Johor Bahru, his father built a shrine to the deity outside their home.

Wong is on his third trip to Kusu. But though he has been in Singapore for 14 years, he only found out this year that there is a shrine to Datuk Gong on Kusu. “My girlfriend told me that people will pray and can strike 4D. I really did strike a big prize, so I am going there to thank him,” says Mr Wong with a smile.

But the Datok Kong of Kusu Island is somewhat different from the one that Wong grew up with. Residing at the top of a 152-step high hillock are two shrines to a pious 19th century family: Syed Abdul Rahman, his mother Nenek Ghalib and his sister Puteri Fatimah.

They are dedicated to, respectively, Datok Kong and Datok Nenek. There are no statues or remains entombed there – merely symbolic tombstones wrapped in yellow cloth, the colour of holiness, and altars to them.

While Wong was surprised by this particular incarnation of Datuk Gong, he says, “It’s all the same to me. I pray for the same things.”

Just as with the earth deity, the shrines attract devotees praying for good health, good business and prosperity. It’s especially popular with childless couples seeking a baby, as well as those seeking 4D numbers. There is even a ritual blessing with many echoes of Chinese religious traditions.

According to caretaker Ishak Samsuddin, 54, they come from as far afield as Malaysia, Indonesia and Myanmar. He even claims that the late President Wee Kim Wee and his wife were regulars at the shrines.

“This is not a god, this is a saint. The thing is alive. You can communicate with it,” says Ishak, whose family has been taking care of the shrine for six generations. He adds with a laugh, “I have seen many miracles here, a lot, too many! The sick get well, businesses do well, couples have kids. (People of ) any religion is [sic] welcome.”

Thangamuthu, 46, a manager in the marine industry, has come to the shrines with eight members of his extended family to pay his respects. A Hindu, he recalls that six years ago, a childless couple he knew conceived after praying at the Kusu shrines. “I believe in all the gods, we don’t criticize them. We will go into churches and Chinese temples, just to give respect,” he says.

For Sri Lankan domestic worker Malee Payarathna, 60, she finds many echoes of her Buddhist faith at the shrines, “We trust the god, so maybe they are helping us. All the things that they do here, we also do in Buddhist temples, just that there are no pictures of statues.”

Uniquely Singaporean

Ultimately, religious syncretism is emblematic of cultural diversity in Singapore, says A/P Indira. The cult of Datuk Gong, being unique to this region, is an excellent example of “an ordinary, un-self conscious and entirely ordinary testament to our acceptance of cultural and religious pluralism”.

“It is one of the phenomena that makes Singapore, despite popular prejudices, a deep, interesting and complex society. Underneath all this sophisticated gloss is a messy, plural and society that is alive and therefore fascinating to study.”

https://sg.news.yahoo.com/datuk-gong–the-god-of-the-chinese–indians-and-malays-073119502.html

Sisters’ Islands to be heart of marine life conservation

22 May 2016

The Straits Times

From Singapore’s first sea turtle hatchery to a floating pontoon with see-through panels, detailed plans to transform Sisters’ Islands into the heart of the country’s marine life conservation efforts were revealed yesterday.

Announcing these yesterday on St John’s Island, Senior Minister of State for National Development Desmond Lee highlighted how, despite covering less than 1 per cent of the world’s surface, Singapore’s waters are home to over 250 species of hard corals, a third of the world’s total.

“We may be small, but we are large in our marine richness,” he said, as he highlighted the need to ramp up conservation efforts and to raise awareness among Singaporeans of the life in surrounding waters. “The marine park is meant for Singaporeans, and we hope our people will love it, grow it and take ownership of this park.”

The 40ha Sisters’ Islands Marine Park, first announced in 2014 and about the size of 50 football fields, comprises the two Sisters’ Islands – which are a 40-minute boat ride from Marina South Pier – surrounding reefs and the western reefs of nearby St John’s Island and Pulau Tekukor. Its ecosystem supports corals, anemones, seahorses, fish and other marine life.

With the help of a $500,000 donation from HSBC, a turtle hatchery will be set up on Small Sister’s Island by the end of next year.

The island will be a dedicated site for marine conservation and research. It will have a coral nursery where rare corals can be grown before being transplanted onto Reef Enhancement Units (REU) on the reef. Yesterday, HSBC also donated $180,000 for nine REUs under the new Seed-A-Reef programme.

Open to the public, donations of at least $20,000 will pay for an REU – an artificial scaffolding to which corals attach and grow. To encourage Singaporeans to take ownership of the marine park on the islands, they will be able to also “sponsor” a coral for $200 in the new Plant-A-Coral initiative.

Big Sister’s Island meanwhile will serve as a “gateway to the marine park” for the public, said Mr Lee. It will have facilities where people can get close to nature, such as a floating pontoon, intertidal pools, a boardwalk and forest trails. Most of these new facilities will be built by the end of 2018.

Ms Karenne Tun, a director at NParks’ National Biodiversity Centre, said each sponsored coral will be grown in aquariums or a coral nursery in the sea from small fragments before being transplanted.

“We will target key species in Singapore that we feel need a bit of help, (or) those that are rare in Singapore,” she said, adding that it can take six months to two years for corals to be transplanted, depending on how fast the species grows.

If these programmes are done right, they could have an “add-on effect on the natural reef”, said Mr Stephen Beng, who chairs the marine conservation group of the Nature Society (Singapore).

Professor Wong Sek Man, director of the National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Tropical Marine Science Institute, said the upcoming plans on Sisters’ Islands will help educate the young on how to protect the environment. “Kids are very curious… to know what kind of marine organisms can be found in the sea. If they can also touch them, it will be very nice,” he said.

NUS first-year environmental science undergrad Lim Hong Yao, 22, who has been on a guided walk with NParks to the intertidal area on Sisters’ Islands, said the zone is full of wildlife. “Everything is interesting… I’ve seen corals, hermit crabs, octopus and even stingrays.”

http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/sisters-islands-to-be-heart-of-marine-life-conservation

Last islanders on St John’s to leave by new year

13 December 2016

The Straits Times

The last four occupants on St John’s Island will have to move to mainland Singapore by the new year.

Two of them, Madam Fauziyah Wakiman, 65, and Mr Supar Saman, 67, work for the island’s managing agent, Sentosa Development Corporation (SDC), and have lived on the quiet island south of Singapore with their spouses for decades.

SDC’s spokesman said the two senior support assistants will be retiring, and the corporation will “hand over the management of the Southern Islands to the Singapore Land Authority (SLA) from March”.

SDC is currently in charge of maintenance of the island and “onsite guest support”.

SLA said it would reveal plans for the Southern Islands, when ready.

Mr Mohamed Sulih, 71, Madam Fauziyah’s husband, will have to say goodbye to a place he has called home all his life.

Mr Sulih, who was born, grew up and got married on the island, told The Straits Times: “I will miss it. I feel sad because I was born here.”

SDC’s spokesman said staff living quarters had been provided for the two staff “for their convenience, in order to minimise travelling time between their homes on mainland Singapore and St John’s Island”.

Island life for Mr Sulih, who retired as one of its caretakers in 2010, revolves around mending nets in the day and catching squid along the jetty at night.

He is also surrounded by a clutch of free-roaming chickens and cares for about 10 cats.

Mr Sulih said he will live with one of his sons in Jurong, and look for homes for the cats. He will give away his boat to a friend. The couple have a flat in Pasir Ris which is being rented out.

Photographer Edwin Koo, 38, who did a project called Island Nation documenting life on Singapore’s Southern Islands, said it was a pity the islanders had to go.

“Why are we booting out people and not attempting to preserve this thread of living heritage?

“I really hope that the authorities will re-think their decision and allow the last few islanders to retire there,” he said.

Frequent island visitor Marcus Ng, 41, a heritage enthusiast and freelance writer, agreed. Mr Ng has been photographing and documenting the island over the past five years.

He said: “It’s a bit of a shame that the couples will no longer be stationed there because it’s nice to have familiar faces around and get a sense that the place is connected to them historically.

“They aren’t just workers but have decades of close association with the place, are reservoirs of information, and provide an intangible connection.”

The island has served as a quarantine station for cholera cases, a holding area for political prisoners and secret-society ringleaders, and as a drug rehabilitation centre.

Over the decades, staff working for these centres made the island their home although most villagers had left for the mainland by 1975, said Mr Sulih.

There was also a reclamation project, started in 2000, to build a causeway to neighbouring Lazarus Island.

The 39ha site continues to draw a steady stream of nature lovers.

http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/last-islanders-on-st-johns-to-leave-by-new-year

Last islanders likely to get to remain on St John’s Island

23 February 2017

The Straits Times

The last few occupants of St John’s Island, who had been asked to leave by this year, may be spending their twilight years on the island after all.

The Singapore Land Authority (SLA), which is taking over the state land from managing agent Sentosa Development Corporation (SDC) on March 1, told The Straits Times it is “working out an arrangement” with the ageing islanders.

A Straits Times article in December, which reported that SDC senior support assistants, Madam Fauziyah Wakiman, 65, and Mr Supar Saman, 67, would retire to the mainland in the lead-up to the corporation handing over management of the island, sparked dismay among the public.

The duo have lived on the quiet island south of Singapore for decades. People saw their fate as the loss of a bygone way of life and asked if it was necessary to uproot the couples.

In its response yesterday, SLA noted that the islanders had lived and worked on the island for many years, and had expressed their desire to continue living there.

SLA’s spokesman said: “We are supportive of their request as they have volunteered to continue contributing to the islands where they can and we are working out an arrangement with them.”

The islanders, who were in the process of moving out, welcomed the news. Mr Supar said he was “happy”.

Madam Fauziyah’s husband, Mr Mohamed Sulih, 71, who was born, raised and married on the island, said: “I’m of course very happy.

“I’ve moved half my belongings to Singapore but I’m glad that they changed their minds.”

SDC, which oversees maintenance of the island and “on-site guest support”, had said in December last year that it provided staff living quarters on the island so the two employees would not have to travel back and forth between the island and the mainland.

The Straits Times understands they will get to continue living in these quarters, and that the matter of an allowance is being discussed.

Among those who had pleaded for the islanders were members of Singapore’s heritage community.

Said heritage enthusiast and freelance writer, Mr Marcus Ng, 41, who is a frequent island visitor: “The islanders can share with visitors the island’s history and how it has changed over the years as first-hand witnesses.

“This is not something you can get from reading a book or an article.”

The island has served as a quarantine station for cholera patients, a holding site for political prisoners and secret-society ringleaders, and a drug rehabilitation centre.

Over the decades, staff at these centres had lived on the island, although most had left by 1975, said Mr Sulih.

http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/last-islanders-likely-to-get-to-remain-on-st-johns

First time read this blog, it’s fantastic! Very details and vivid historical stories, highly appreciate!

Today I read again in details, it’s really great stories with interest.

Loud explosion heard as fire breaks out near Malay shrines on Kusu Island hilltop

18 April 2022

The Straits Times

Several explosions rocked the evening air and thick smoke billowed from Kusu Island on Sunday (April 17) after a fire broke out at a hilltop where three Malay keramats (shrines) are located.

Witnesses who saw the fire from nearby Lazarus Island said the blaze started at about 6.20pm. The Police Coast Guard, Singapore Civil Defence Force (SCDF) and Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) later arrived at the scene. Heavy rain helped to douse the flames, which looked to have engulfed the area near the shrines.

Mr Vitor Hong, 42, was camping on Lazarus Island with four friends when they heard a loud explosion followed by smaller ones.

“The fire was very big,” the engineer told The Straits Times, adding that smoke from the blaze had covered one side of the 8.5ha island. He said a firefighting boat arrived at about 7pm and the fire looked to have died down by about 8pm, due in part to the downpour.

Mr Nur Muhammad Khayzan Abas, 41, who was on a yacht near Lazarus Island, said he did not hear any explosions but smelled something burning.

“I thought it was something to do with my vessel. But when I looked towards the sky over the Kusu Island area, there was black smoke,” said the yacht captain.

As he was ferrying passengers, Mr Khayzan said he had to head back to One Degree 15 Marina at Sentosa Cove. On the way, he passed by Kusu Island and saw the hilltop engulfed in flames.

At the Kusu Island pier were a Police Coast Guard boat and an MPA boat, he said. He did not see any day-trippers or recreational activity. “Usually at about 6.30pm, there is no longer a crowd there,” he added. SCDF said its marine and land-based firefighting forces responded to the fire amid a heavy downpour.

A Marine Rescue Vessel (MRV) and a Rapid Response Fire Vessel from Brani Marine Fire Station and West Coast Marine Fire Station were despatched to the island, along with firefighting crew from Marina Bay Fire Station.

Using the MRV as a water pump, firefighters laid hoses from the Kusu Island jetty to the top of the hill, covering a distance of about 520m, SCDF said in a Facebook post late on Sunday night.

The fire, which was raging at the cluster of shrines atop the hill, was put out with two water jets within an hour of SCDF’s arrival. There were no reported injuries, SCDF said, and the cause of the fire is being investigated.

Managed by the Singapore Land Authority (SLA), Kusu Island is home to the three Malay shrines as well as a Chinese temple.

During the ninth lunar month, which falls between September and November, an annual pilgrimage to the island attracts thousands of devotees who visit the Da Bo Gong (Tua Pek Kong) Temple located closer to the pier.

After paying their respects at the temple, many devotees will climb 152 steps up a small hill to visit the shrines of three Malay saints. According to the SLA’s website, the shrines were built to commemorate a 19th-century pious man, Syed Abdul Rahman, his mother Nenek Ghalib and sister Puteri Fatimah.

https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/loud-explosion-heard-as-fire-breaks-out-near-malay-shrines-on-kusu-island-hilltop